The Bare Minimum Video Game: The Odyssey 100

The first video game? Debatable. The first video game console, though, is well-established: the 1972 Magnavox Odyssey, brainchild of Ralph Baer. However, the Magnavox Odyssey was expensive to make, so Magnavox turned to Texas Instruments to create a stripped down version of the Odyssey. A stripped down version of the first and most primitive console? Oh yes, now we’re really deep in it. PLUS: Composite mod on a black and white console! 3D printing! Video signal probing with an oscilloscope!

Odysseus, save us

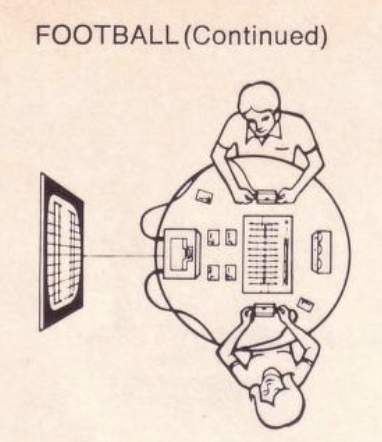

The Magnavox Odyssey is the first video game console. Magnavox patented it, courts agree, so we know it has to be true. But there’s some of what the TV Tropes crowd would call ‘Early Installment Weirdness’– the concept of a “video game” wasn’t quite the same in 1972 as it is today. Here’s a picture from the Odyssey manual, showing a game of Football. Clearly this was an important game, so many pages in the manual are dedicated to it; and look at how you play it:

The television is practically an afterthought, though it is used for plays. Much of the game happens as a board game, with no less than six decks of cards. Graphics are provided by a piece of plastic that attached to your CRT television screen with static electricity. This doesn’t look much like someone playing a video game today. Most Odyssey games were like this to some degree or another.

The exception was in the first game card– oh, yes, the Odyssey did have “game cards”, though they weren’t cartridges in the modern sense (Football uses two different cards for different types of plays), only connecting and disconnecting different parts of the internal logic. They also served as the power switch; you literally pull out the cartridge to turn it off. In any case, that exceptional game was Table Tennis, Game Card #1.

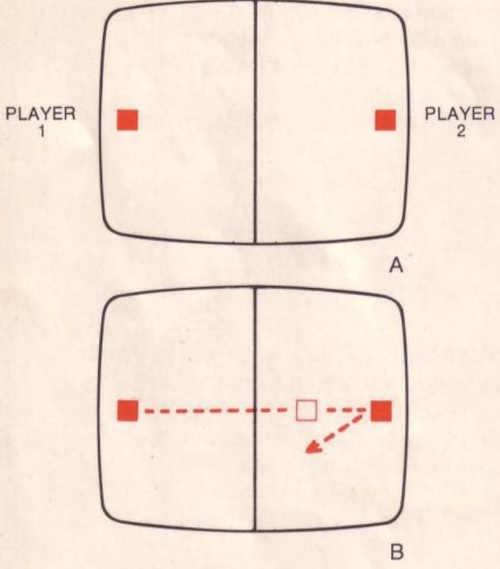

Odyssey Table Tennis was famously the inspiration (proven in court) for Nolan Bushnell’s Pong, though more on that later. Two spots of light move about on screen, with a center line dividing the court in two. They can push a ball of light back and forth between them, strategizing to hit the ball such that the other player will miss.

The Magnavox Odyssey is sometimes called a failure, but it’s hard to say that Magnavox thought of it that way; 350,000 units was more than any other video game console before it sold. They invented the concept of selling additional game cards, and even got Nintendo to manufacture a light gun. But the 1970s were a time of high inflation, and the Odyssey wasn’t cheap to make. Plus Ralph Baer, ever-curious, wanted to take advantage of the newfangled integrated circuit technology.

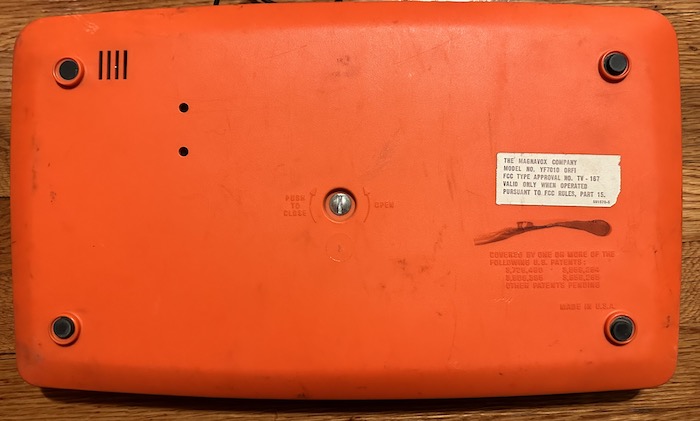

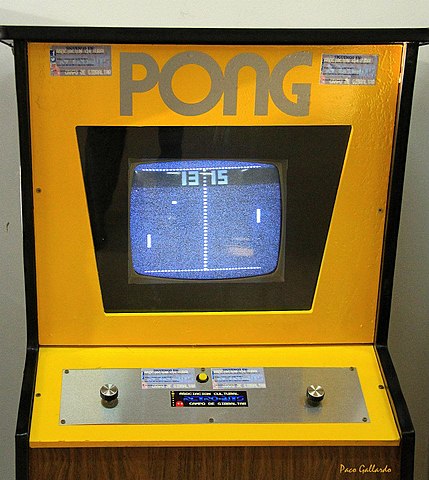

Behold: the 1975 Magnavox Odyssey 100. It’s in a bit of a rough shape, isn’t it?

Where we’re going, we don’t need features

The back of the Magnavox Odyssey 100 is held on by a single screw. If you open it up, you’ll see a cardboard overlay, showing various adjustment knobs, but warning you not to go any further. Notice the “Score Vert. Pos.” knob; this same cardboard overlay was used for the Odyssey 100’s sister console, the Odyssey 200. This isn’t an Odyssey 200, though, so don’t expect a physical score. You saw those sliders on the front! That not good enough for you?

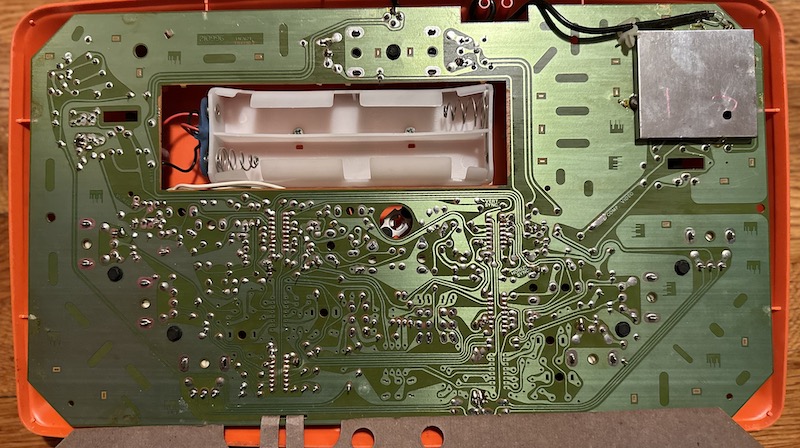

There’s also a position for a whopping six batteries. Notice that conveniently, the motherboard surrounds the battery compartment on all four sides, so that if this was left in a closet in 1975 with batteries left in, and those batteries had leaked in the intervening forty-eight years (which they almost certainly did), some part of the board will surely be destroyed. If you want to buy one of these, or another of the numbered Odysseys that used the same style of case and took batteries, make sure to get an inside photo before you buy.

Underneath the cardboard you’ll see the main PCB. It’s held in by six bolts, which is really annoying, and is single-sided. It’s quite cardboardy.

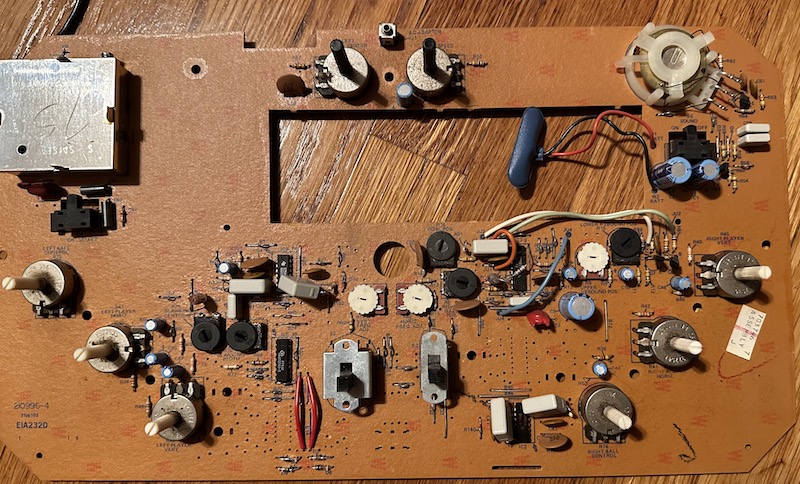

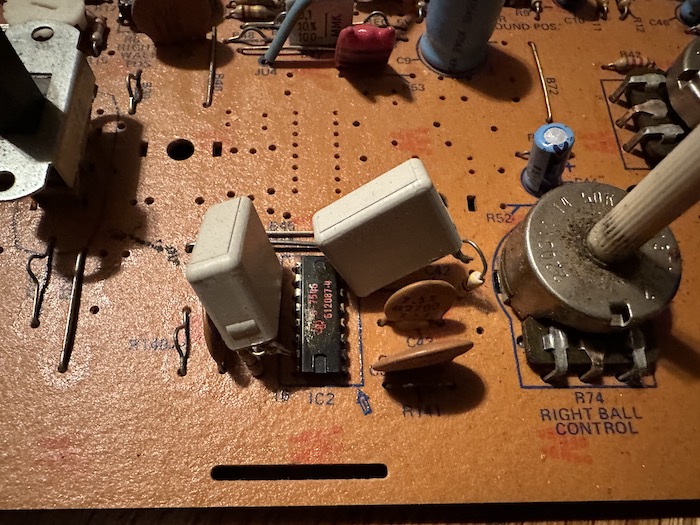

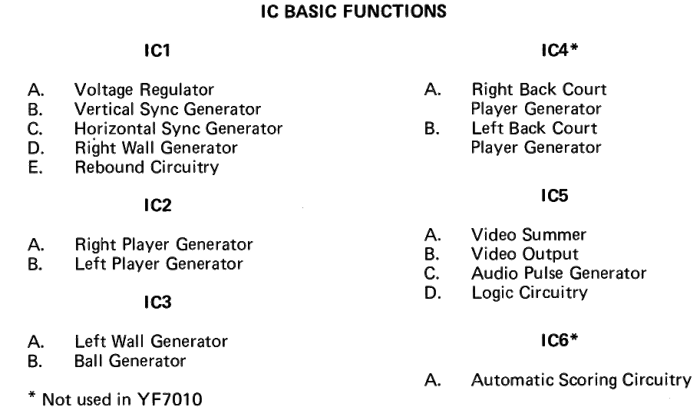

Wow, newfangled ICs! Of course, there are four of them, nestled between the components; the idea of doing a whole table tennis game with a single IC would have to wait for the distant future of 1976.

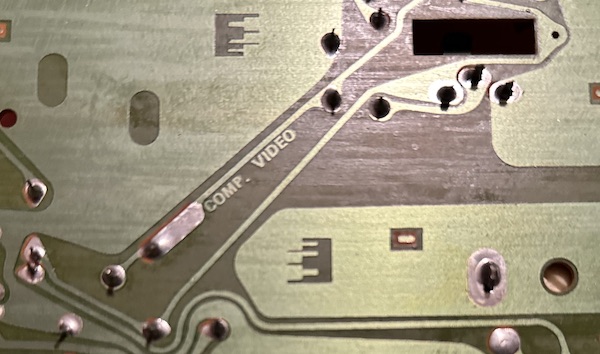

One thing I find interesting is that there are holes drilled for additional ICs; these would be used on the Odyssey 100’s partner in crime, the aforementioned Odyssey 200, which added additional features, including even a primitive form of on-screen scoring. (What, you thought Nintendo invented the strategy of sharing parts between two models?) The thing that surprised me is not that they share a PCB– that’s pretty common– but instead that the silkscreened text is version-specific; the ICs that don’t show up on the Odyssey 100 aren’t labeled here.

Another evidence of shared hardware with the Odyssey 200 is this third hole in the plastic. On the Odyssey 200, both switches change game options, while the power switch is on the bottom. That isn’t the case on the Odyssey 100. Even though they’re different colors, it seems the same molds were used. Another construction oddity you might just manage to make out is the fact that the dust covers on the switches are actually between the plastic of the case and the outer sticker, rather than parts of the switches or even under the case. I ended up having to remove the one on the power switch.

“Composite” “Mod”

The real reason I opened up this Odyssey, though, is this connector on the end of the hard-wired cable. I’ve never quite seen a connector like this before; apparently it was only used by Magnavox on their early consoles. (The original Odyssey had it detachable at both ends, which is very luxurious) My Odyssey 100 didn’t come with the RF box, though, so I have no way to deal with this.

But that’s fine! I can do a composite mod. What’s that, you say? This console isn’t in color, so it’s not really composite video? Well, who are you to tell Magnavox they’re wrong?

Of course, it is a composite of video and sync… or perhaps a composite of all the various movable elements. In any case, it’s called composite video, and Pong-Story.com says I can just wire up an RCA cable to it, no amplifier or anything. I guess these older systems are just made of sterner stuff. I removed the old cable and threaded my new, much shorter cable through the hole.

Having given the Odyssey 100 a bob cut, I complete the look by 3D printing a new potentiometer knob. Oh, you didn’t know I had a 3D printer? Thank my wife for that one; this is actually my first use of it; a Creality Ender 3 Neo Max. The model isn’t a perfect match (definitely not shiny enough) but it looks good enough in the dark; here’s the SCAD and STL files if you want to mock my first attempts. It’s not a perfect match, but it looks fine from a distance.

Still not talking about the games

So with the Odyssey 100 looking pretty and all buttoned back up, it’s time to get it on-screen. I had to use a 3.5mm to 2.5mm mono adapter with my Atari 2600 power supply; while I complained about the use of a plug I associate with audio in the 2600 article, I admit that this is more understandable here: the 2.5mm plug has an internal switch that disconnects the batteries when a power supply is used. After getting everything powered, though, I ran into an interesting issue: the Odyssey doesn’t actually work with my Sony PVM. The image rolls.

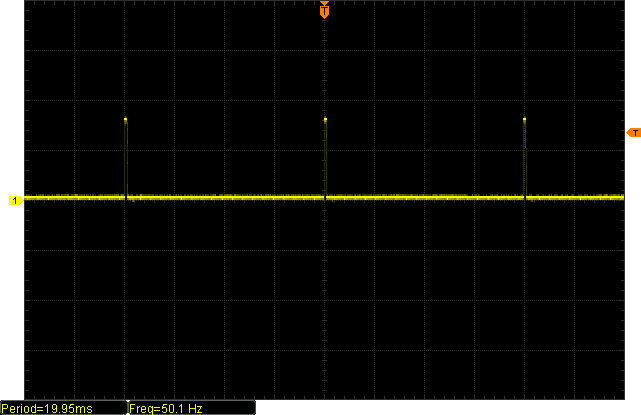

Why is that? A quick look at the oscilloscope (I have one of those now too! Wow I feel like a real content creator) shows that for some reason the frequency has dropped to 50Hz. This isn’t supposed to be PAL!

Adjusting it up to 60Hz with the provided potentiometer didn’t seem to help though. This is a weird case where the Framemeister did a better job with a signal than a real honest-to-goodness CRT! I never thought I’d see the day.

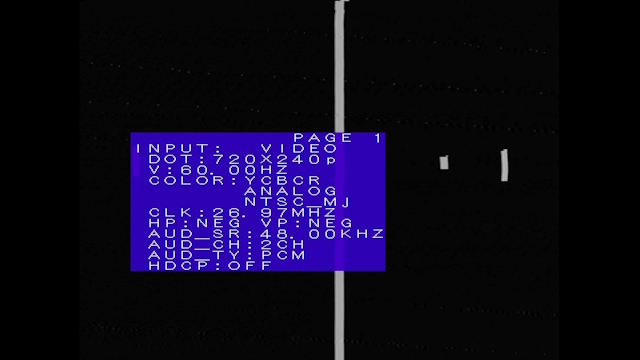

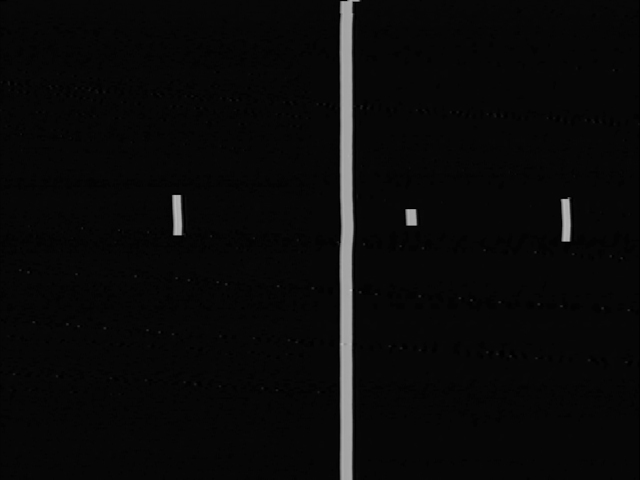

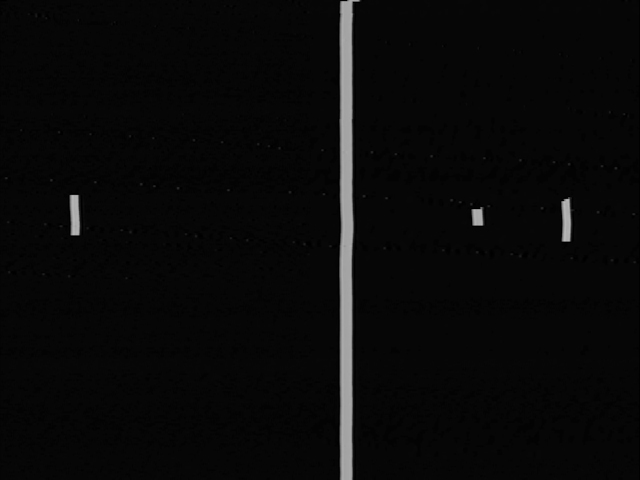

Maybe we should talk about that signal, and see what’s so weird about it. Let’s take a closer look. Right now, the game console is in Game A, which looks a lot like Pong Magnavox Odyssey Table Tennis: two paddles, one ball, and a center line.

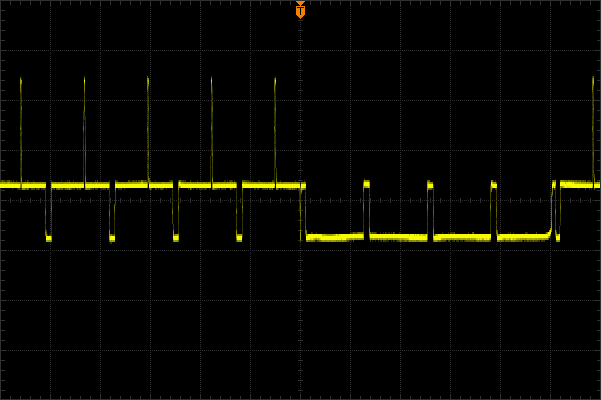

So what does the signal of this game mode look like? Remember that the screen is drawn one line at a time, in series. There are a series of “horizontal sync pulses” that mark the beginning of each new scanline, and goes into the region known as “blacker than black”, since the voltage is lower than the lowest visible color.

Here, we’re looking right around the vertical sync region. This is where for several scanlines, the whole video signal goes into that “blacker than black” region. The horizontal sync pulses are now inverted– missing these pulses in the vertical sync region was one of the issues that made Dottori-kun a pain to get video output from.

This is pretty typical of a monochrome video signal; there’s no “color burst” or any high frequency signals to complicate the picture. However, notice that each scanline that’s visible has the high narrow pulse that signifies the white central line; in most game systems, the region around the vertical sync pulse, known as the “vertical blanking interval”, has no lines displayed.

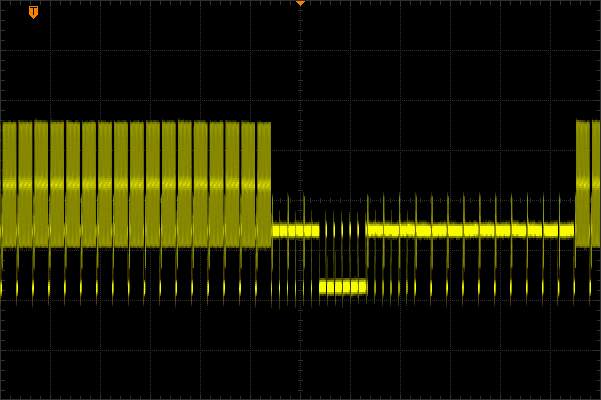

Here’s what that looks like on my Panasonic FS-A1F MSX machine; note that what might look like signals are the color burst, which remains on each line except during the vertical sync pulse itself.

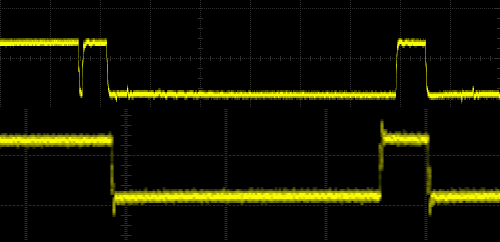

Let’s take a look at the very beginning of the vertical sync region. Top is the Magnavox Odyssey 100, and the bottom is the MSX signal. (A bit distorted as I took the trace at the wrong frequency, but don’t mind that)

Notice the weird timing of the signal; it’s almost like the vertical sync period started in the middle of a horizontal sync. And that’s exactly that happened. After all, did you notice that on the Odyssey 100’s board, there are two different adjustments for horizontal and vertical timing?

That might make sense on the back of your TV, but it doesn’t make sense for something that produces a signal. Typically, it would have a single oscillator, and it would know how many horizontal lines it created. You don’t need a CPU to do this; a simple counter IC would do just as well.

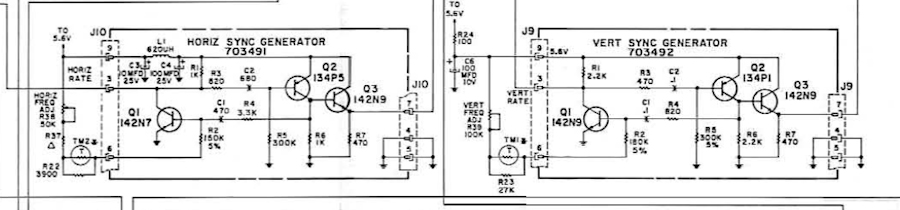

But the 1972 Magnavox Odyssey (the original) didn’t have any ICs. And rather than build a counter of series of individual transistors, Baer took a simpler approach: the horizontal and vertical sync pulses are generated by two completely separate astable multivibrator circuits. Which is to say, the Magnavox Odyssey isn’t just a pre-CPU console. It’s downright analog.

Take a look at the service manual; the two are different circuits that don’t interact. While the Magnavox Odyssey 100 does consolidate the circuits into a single chip (IC1, which also includes the voltage regulator, somewhat strangely), it keeps separate oscillators for vertical and horizontal. It really is mostly just a consolidation of the original Odyssey.

Gameplay

I told you that the Odyssey 100 was a stripped down Magnavox Odyssey. And in some ways that’s true. It has no overlays, ditches the detached wired controllers, the light gun, and the option for different behavioral cards. However, it does refine the gameplay of Odyssey Table Tennis.

But to explain this, first we have to look at Odyssey Table Tennis. It was, according to a court of law, the inspiration and origination for the famous Atari game Pong. However, the two are actually from a player’s perspective very different games.

I’m not talking about features like on-screen scoring, but actual gameplay. In Pong, you use a single potentiometer to move vertically on a playfield. Your horizontal position is fixed. The ball ricochets off your paddle, with the angle changing depending on where on your paddle the ball hit. (This gameplay feature is called a “segmented paddle”) The ball bounces off of the top and bottom of the screen, and the game plays sound effects when the ball bounces.

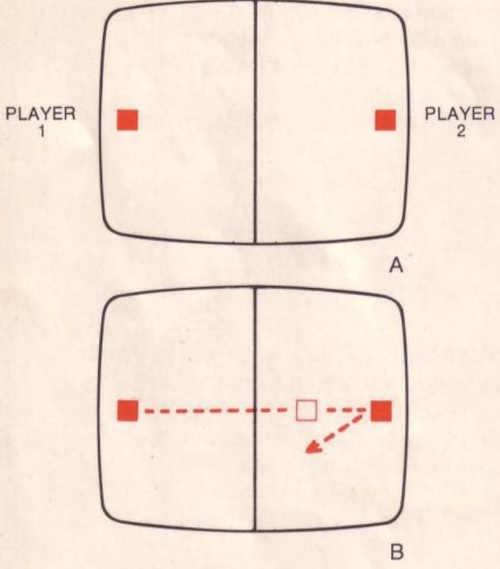

What about on the Odyssey?

The Magnavox Odyssey has no beeps; the console is silent. You use two potentiometers to move horizontally and vertically. Additionally, you have a third potentiometer, called the “English”. After the ball hits your paddle, you can use the “English” to control the vertical movement of the ball while it bounces back. If you move it off the top or bottom of the screen, that’s a you problem, and the Odyssey manual calls it a foul. If you move it past the opposing player’s side of the screen, you get a point. Press the reset button and start again.

The “English” potentiometer, so named because it simulates “putting a little English on the ball” (potentially just an American phrase? It refers to putting spin on the ball to change its trajectory), is crucial to the gameplay of Table Tennis. Pong doesn’t have this element because of the segmented paddle, but on the Odyssey without the English knob, the ball will always bounce horizontally, which isn’t a very fun game.

Game A on the Magnavox Odyssey 100 is a slight refinement of Odyssey Table Tennis, with just a few differences, as well as having the controls moved to the device housing.

- The ball can no longer be moved out of the top or bottom of the play area. A “rebound” circuit will take over and block attempts to add too much “English”.

- The ball now serves automatically when the ball is off-screen, and the serving player moves their paddle to overlap the white vertical center line. You no longer serve the ball by resetting the console.

- The paddles are now vertical, not squares.

- A speaker beeps when you hit things with the ball.

Numbers 1 and 2 were required by the Odyssey 200, which features a primitive form of on-screen scrolling, so you couldn’t be constantly resetting things; it was nice of them to be included on the Odyssey 100 as well. As for numbers 3 and 4, well, if Magnavox did borrow some inspiration from Pong, it’s just fair turnabout.

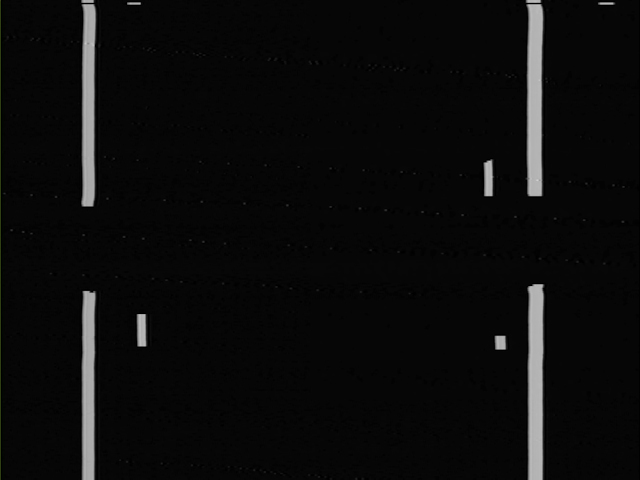

Where the Odyssey 100 really goes beyond the bare minimum, though, is Game B.

In this game mode, the center line becomes your leftmost goal (thankfully, a convenient potentiometer allows you to move it to the left side) and a new right line appears. Unlike in Game A, the ball now interacts with these lines; one downside of this game mode is that it’s a bit confusing who can use “English” after the ball bounces off a wall. The original Odyssey had nothing comparable to this game mode.

Because this is still an Odyssey, and an analog video game console, the positions of the gaps in the goals are controlled by a potentiometer on the circuitboard. Above, I tuned the goal positions when the Odyssey 100 was still running at 50Hz, so when I fixed it to run at 60Hz, they suddenly became too low.

Overall the Magnavox Odyssey 100 is probably not the most interesting console in the world. It’s probably not the most fun console in the world. But its circuitboard is very mind-blowing in a particular way. Typically in video game hardware, one thing you learn quickly is that something like Truxton isn’t going to have, say, a “player” chip or a “bullet” chip. Gameplay elements the player sees are built out of even more base features of the hardware, like sprites and tilemaps. But take a look at the Odyssey 100’s service manual:

Wild!