The Pioneer LaserActive: NEC Style

The LaserDisc is one of the coolest media formats out there. (It’s huge, shiny, and has “laser” in the name. That’s objective coolness in my book.) The TurboGrafx-16/PC Engine is one of the coolest game consoles. (Johnny Turbo did not pay me to write that) But what happens when the two combine? Well, uh, not much.

Some background info…

The LaserDisc, also known as LaserVision, DiscoVision, CD Video (not to be confused with Video CD), MCA DiscoVision, or the Reflective Optical Videodisc System, is a video system that stores movies on 12-inch plastic reflective optical discs. It was the first mainstream optical disc format being released in 1978, though on the market it was always well behind VHS, before finally being killed off by DVD in the late 1990s.

Optical discs in 1978, you may scoff. Digital video compression technology of that time was basically non-existent! But that didn’t matter, because Laserdisc is essentially an analog format; though there are “pits” and “lands” like the later CD, DVD, and Blu-ray formats, they vary widely and don’t store zeros and ones. Instead, an analog, composite video signal is stored, with stereo audio track stored using FM encoding, similar to how it’s broadcast over the air. (You’ll sometimes hear this called PCM, or pulse-code modulation, but that’s not quite right– it’s an entirely analog process, there is no digital-to-analog converter involved)

So there is the Laserdisc format:

- Huge optical discs

- Analog-encoded video

- Composite only (240p or 480i, essentially always 480i)

How on earth do you make this into a video game format?

The Pioneer CLD-A100 LaserActive

The Pioneer CLD-A100 is quite a good-looking machine, as all Pioneer Laserdisc machines are. But a closer look will show that it’s also not particularly high-end. No double-side play, no Dolby, and not even a screen on the front. If you were just expecting this to be a regular laserdisc player, you’d probably be a little bit disappointed.

You’d be even more disappointed by the fact that it has a giant hole in the front, though. That came with a cover originally, of course, but as is common when buying second or third-hand electronics, it’s long lost. But this is what makes the LaserActive… active. Without anything installed in that slot, this really is just a low-end 1993 Laserdisc player.

See, when they decided to turn the Laserdisc into a video game format, Pioneer realized it’d be silly to try to release their own console. Instead, they decided to work with the existing manufacturers. Unfortunately, manufacturers is indeed plural there. Both Sega (manufacturers of the Mega Drive/Genesis) and NEC (manufacturers of the PC Engine/TurboGrafx-16) were convinced to allow Pioneer to create add-ons that would make their CD-based game systems into Laser game systems. Well, Laserdisc. CDs use lasers too.

Today we’ll be taking a look at the PAC N-1, which allows one to play PC Engine games, and “LD-ROM2” games, which is a Laserdisc derivative of the “Super CD-ROM2” system. I’ll give some more details on that later, first let’s get this thing booted up and see how it works as a PC Engine.

As an aside, there was a release of this in the US, but as the TurboGrafx was a bit of a flop, they’re very rare. Thankfully, Pioneer didn’t region-lock games. (TurboGrafx card games are region-locked, but CD games aren’t)

Let’s turn this sucker on!

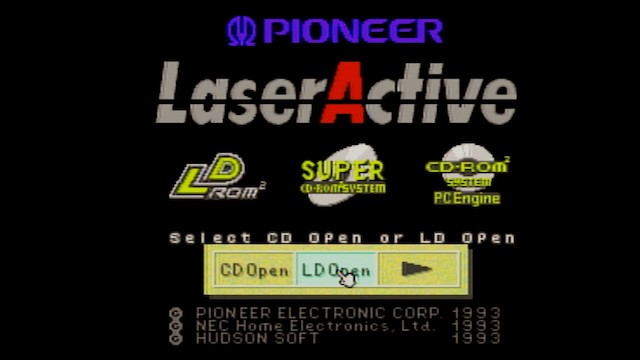

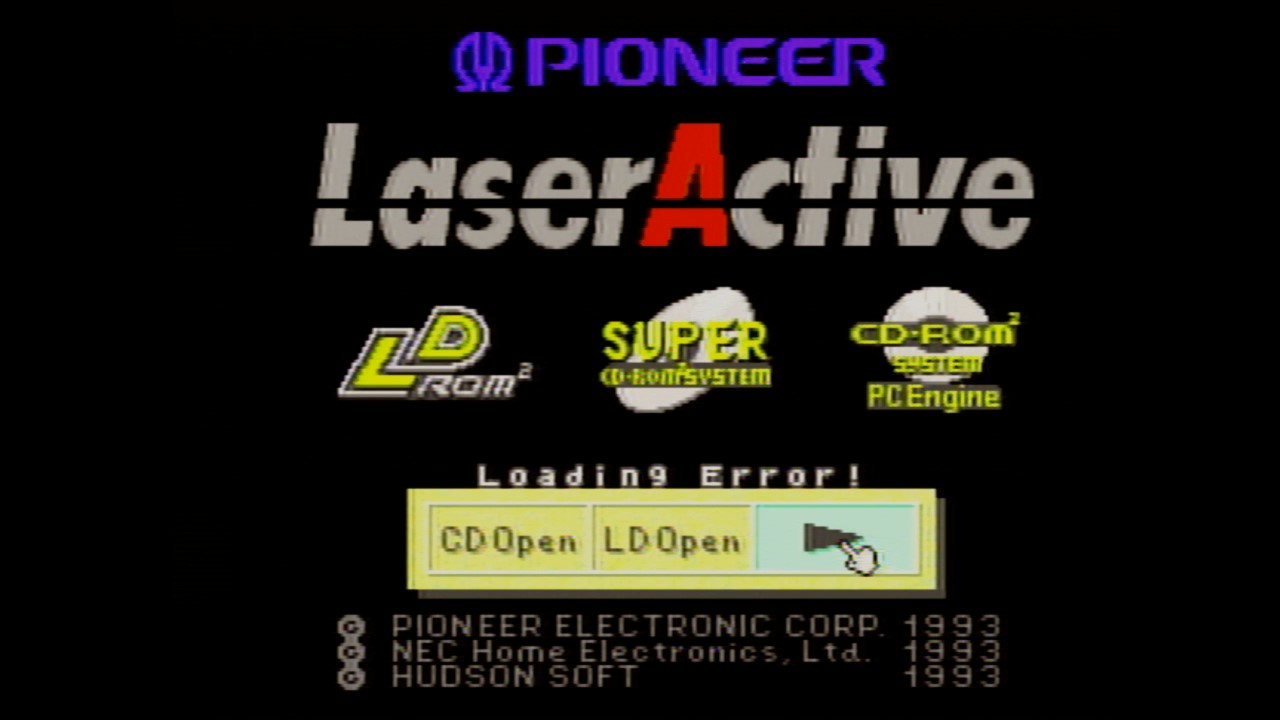

Without the PAC installed, the LaserActive boots to a black screen and waits for you to do something. With it installed, though, we get this nice screen. Notice that it can open the CD or LD trays from software just by selecting the option with the controller; this is actually the only tray-loading CD system for the PC Engine family of consoles, so it’s the only one with this feature.

While the system is on, a spring-loaded plastic tab comes down that prevents you from inserting or removing anything into the HuCard slot. (I’ve had to enhance the above image, it’s very subtle and I actually hit it by surprise) Like all HuCard slots, this one is region locked, in the case of the PAC N-1, for the Japan region.

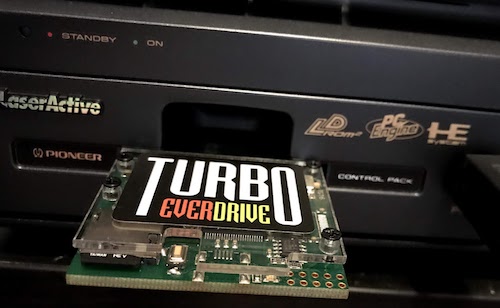

Another problem with the HuCard slot is that the Turbo Everdrive doesn’t fit; all you have to do to fix that is to remove the plastic cover, though. The system doesn’t have any problem with official oversized HuCards like Street Fighter II’ or the Tennokoe Bank. It plays all HuCards fine, but only with composite output of course.

The PC Engine is well-known for being able to be RGB modded, and even for providing the RGB output on its expansion bus. However, there’s no point in RGB modding a LaserActive; remember, Laserdiscs are an entirely analog composite format. So with an RGB output, you’d be missing the whole point of the system. It’s a real shame, though, because the composite output of this system is not great, regardless of what upscaler I used.

Playing CD-ROM2 games

The PC Engine had three different formats of CD-ROM games, all of which shared the CD-ROM2 branding (pronounced, somewhat logically, CD ROM ROM). These differed only in the amount of RAM that was available for games.

Unlike a cartridge game (like we explored with Aspect Star “N”), a game console or computer can’t execute code directly from a CD (or a floppy disc, or a hard drive). It needs to be copied to RAM. Having more RAM means that the game can execute more code without loading from the CD as often, which is much slower.

- CD-ROM2: 64kB

- Super CD-ROM2: 256kB

- Arcade CD-ROM2: 2MB

The NEC PAC is equipped to the Super CD-ROM2 standard. I didn’t run into any incompatibilities with US or Japanese games, including both Super CD-ROM2 games and older CD-ROM2 games.

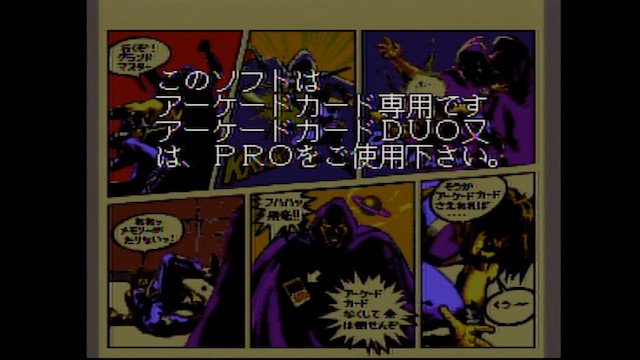

Of course, to play Arcade CD-ROM2 games, you’ll need to install an Arcade Card. One interesting thing I learned here is that the Arcade Card DUO, which I used, doesn’t have a BIOS of its own. Instead, it uses the CD BIOS of the system that it’s attached to. Therefore, you’ll still get the LaserActive menus.

Other CD-based formats

So, this can play all NEC PC Engine games (HuCard region lock notwithstanding). But can it play the games of the Engine’s little sister, the ill-fated PC-FX?

Obviously not.

I’m curious why it says “Loading error”, though. Usually, when you insert a CD it goes into the CD player. It’s possible there’s some sort of signal that the system is using to detect games that’s the same between the CD-ROM2 and the PC-FX, but I’m not sure.

The CD player is pretty basic. However, my PC Engine Duo-R doesn’t have any CD player at all, so it’s welcome. I don’t have any CDs with CD+G, sadly, so I couldn’t try out that functionality. I have no reason to believe it wouldn’t work, though.

UPDATE: Nathan M. on Twitter let me know that the PC Engine Duo R does in fact play audio CDs, in the obvious way. I have no idea why I thought it didn’t. And to think, I’ve been playing my audio CDs in my Sega CD like a plebian.

And now, the the LD-ROM2

Laserdisc games for the PC Engine use a format named LD-ROM2. It’s based off of the Super CD-ROM2 format, with 256kB of RAM. But Nicole, you might ask. You just explained that DiscoVision is an analog format. PC Engine games, like literally all software, is digital. It being analog just doesn’t make sense.

And that’s true. However, in 1985, Pioneer introduced digital audio to the LaserDisc format; this is essentially CD-quality, and the PCM-encoded data is embedded “on top of” the analog video data; this kind of trickery is something you can get away with in the analog realm. LD-ROM2 takes the CD-quality audio data for itself, giving 540MB of digital data for the game to stretch out in.

This is less space than a typical CD-ROM. However, remember that this is on top of the existing video (and its analog audio data). The discs themselves are encoded in “CAV” mode, where the angular speed of the player is constant. If you’re familiar with Laserdisc, this enables all sorts of “trick-play” frame-by-frame playback features at the cost of less video space. It’s also visible: you can see the patterns in the disc.

Shut Up And Play

For the time being, I only have one LD-ROM2 game: Vajra Ni. Let’s plug it in and check it out.

Oh yeah!

Wow!

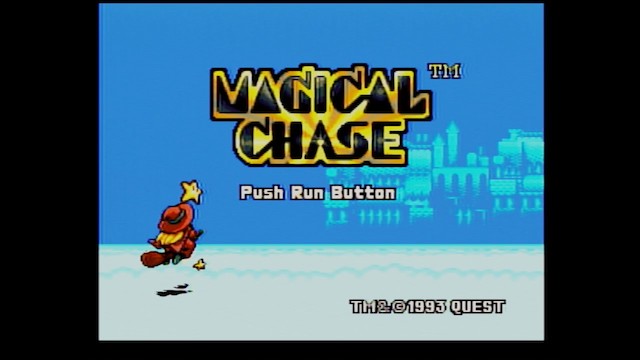

Remember, the PC Engine has an 8-bit CPU and a 16-bit graphics chip (with 9-bit RGB palettes) that doesn’t even have multiple background layers. Certainly, this sort of graphics are far beyond what it’s capable of.

One fun thing is that the main menu is two video frames. This is basically using those “trick-play” frame-by-frame playback features I mentioned earlier. The downside here is that you can see the whole screen shift slightly when you choose an option.

But all of this is just video and graphics. When do we get to the game?

Well, that’s the real downside of the LaserActive. All it really has is video and graphics; if you wanted to make a game for anything else, you’d make it on a CD so that far more people could play it, rather than the tiny number of people who bought Pioneer’s overpriced Laserdisc player and add-on.

And therefore, Vajra Ni is no exception. Here it is:

It’s a crosshair on top of a video. It’s definitely a competent crosshair shooter and can be fun, but it’s also a bit slow-moving, and even on normal mode it’s easy to get overwhelmed by enemy shots. Worse, the auto-scrolling nature means that as soon as you die, you have to go through the whole level again at the same pace.

As an aside, one thing that really confuses me about the LaserActive is the lack of certain FMV games. Dragon’s Lair and its sequels used laserdiscs in the arcade. This should’ve been an opportunity for a perfect port; but it didn’t happen. There’s no Dragon’s Lair or Space Ace on LaserActive.

There is a version of Time Gal for the Sega PAC, but it seems to have been a limited release and goes for well over $1000. For that kind of money I’ll put up with the Sega CD version, thank you very much.

It really feels like a missed opportunity. There are plenty of crosshair shooters, though.

What about movies?

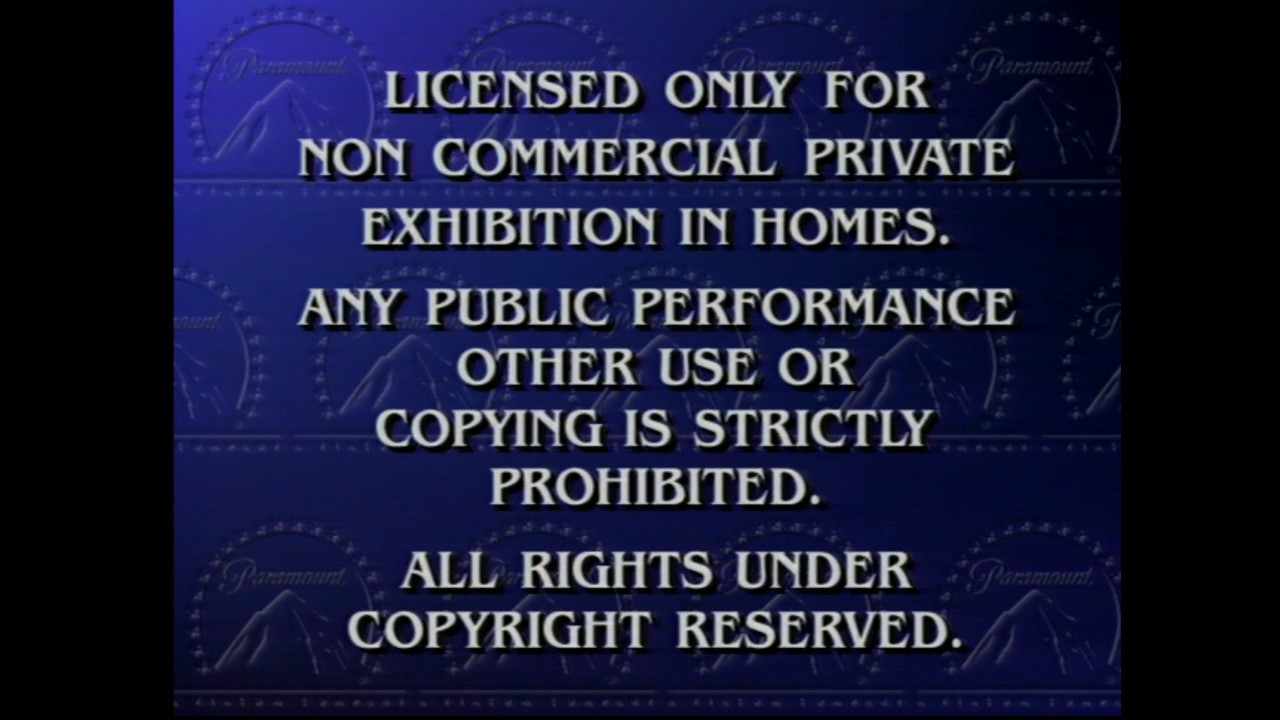

So, we talked about playing PC Engine games, PC Engine CD-ROM2 games, LD-ROM2 games, and even playing music CDs. But the LaserActive has one more trick up its sleeve: it’s a laserdisc player! It can play laserdiscs!

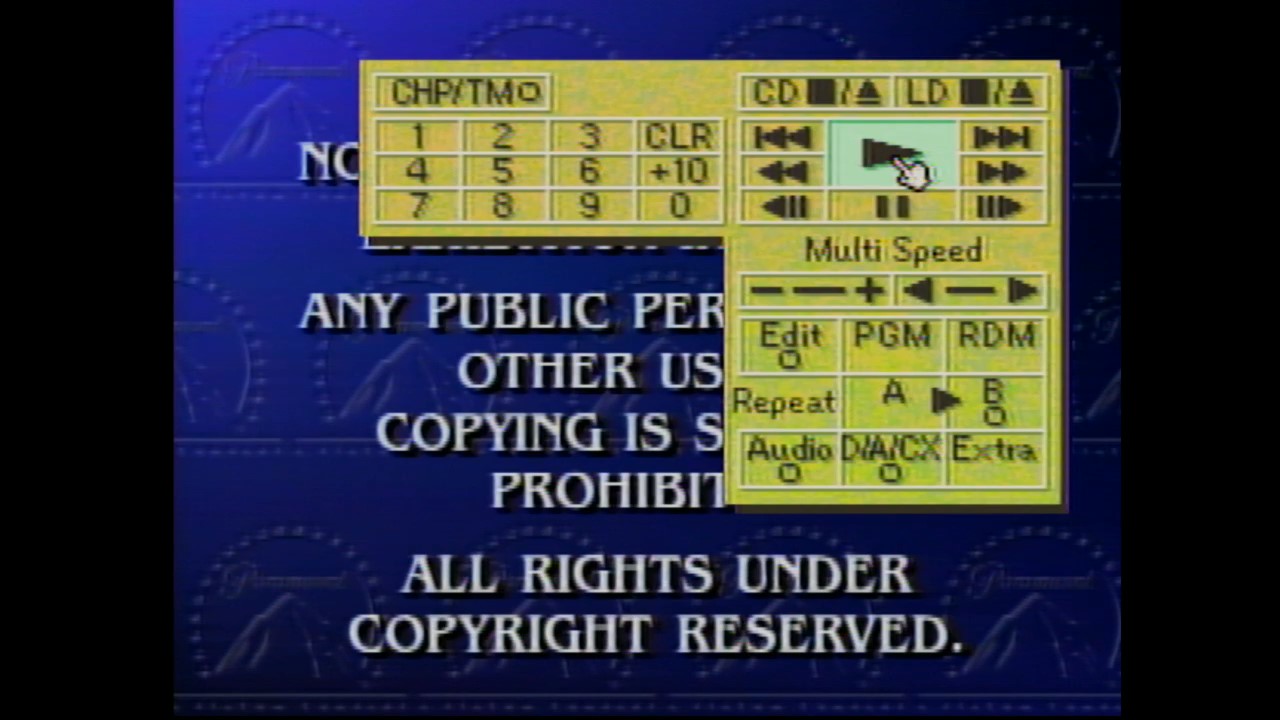

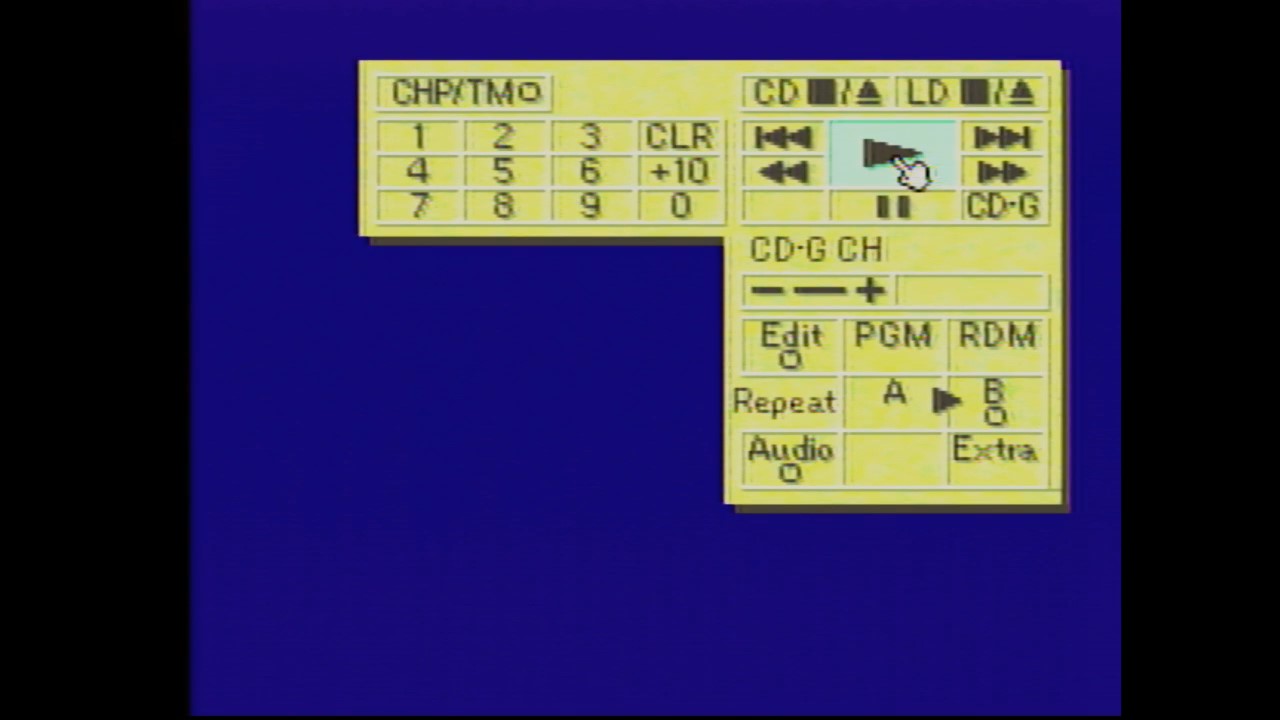

And, the PC Engine circuitry is still active while it plays those movies, and can be activated as a screen overlay. Remember when I mentioned that the Laseractive didn’t have any sort of front display? With a PAC installed, it doesn’t need one.

From here, you can do all the things you’d expect: choose chapters, fastforward, rewind, etc. On a CAV disc, you can do the trick-play features just like you had a remote with a jog-shuttle. (I didn’t get a remote with my CLD-A100, sadly)

But there’s a small catch. Did you notice? Click on the above two images for a full size version, or just keep reading.

The video quality is reduced when the menu is open. The text is still fine and readable, but it’s definitely noticeable. What’s going on?

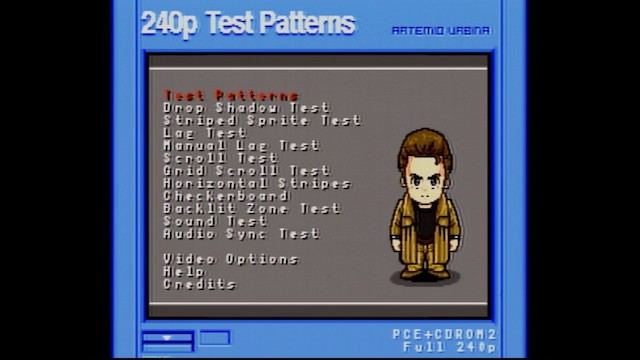

The PC Engine is a 240p console; 240 horizontal lines, being progressively scanned and displayed at 60 frames per second. Normal composite video like you’d find on a laserdisc is 480i, 480 horizontal frames, interlaced so that the overall picture is rescanned at 30 frames per second. Game consoles of this era couldn’t quite do 480i within-spec, and the higher frame rate of progressive scan was better than the higher resolution of interlaced, so this was a fair tradeoff.

But to put the video from a PC Engine on top of a composite video signal, the Laseractive has to convert it to 240p. Remember, this system is outputting over composite. Therefore, the resolution when the menus are open is lower. Now, I’m not being quite fair here by using text as a comparison; this is probably the worst-case scenario. Motion on interlaced video is lower resolution anyway.

It’s also worth noting that this image is from a 1995 movie. It’s a very high-quality conversion, they had the format pretty much mastered by then. If you look at older movies, like this LaserVision promotional animation from a 1982 film, I really can’t tell the difference at all with the menu open:

You might be wondering how they dealt with this issue on the LD-ROM2 games. On those, they just encoded the video on the disc as 240p. Higher frames per second is almost always more valuable in a video game environment, so it’s not really a problem in practice.

That’s all

So, the Pioneer CLD-A100 LaserActive with the NEC PAC N-1. As you can probably guess, it wasn’t very successful on the market. Nevertheless, given NEC’s next console, the PC-FX, would also focus heavily on FMV gaming, you can’t really criticize Pioneer for going down that path.

It’s an interesting oddity. But in the end, that’s all it is: an oddity. It’s not the best Laserdisc player you can get, by any means. It’s not going to open your eyes to a world of vast new gaming possibilities. It’s just another failed console from the early 90’s that bet too hard on FMV’s. But it’s the only one that lets you handle giant optical discs while doing so.

I have a Sega PAC coming in the mail, but it’s currently delayed due to the global situation at the time this blog post is being written. If there’s any interesting followups to this, I’ll probably write a follow-up, but I think with this I have a pretty good idea of what the Laseractive can do, and what it can’t.

Now, if you don’t mind, I’m going to listen to some music.