Yes, You Can Play Duck Hunt Without a Television (but I can't)

Duck Hunt is considered a classic of the Nintendo Entertainment System. But surprisingly, the concept of hunting ducks did not originate in 1984– people have wanted to hunt ducks since at least 1951, when Daffy Duck proclaimed it to be “Duck Season” in the Looney Tunes short Rabbit Fire. But Nintendo didn’t make video games that connected to your television until 1977. What if I wanted to hunt ducks in 1976? BONUS: The ducks are immortal!

Duck Hunt

Duck Hunt? Without a TV? Actually, it’s got quite a long history.

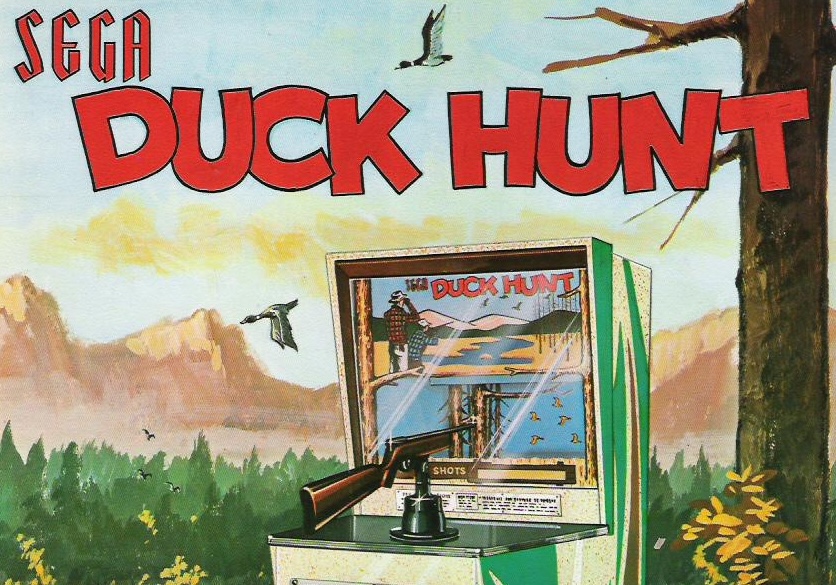

In this case Nintendo was doing what Seg-already-did, as Sega had Duck Hunt as early as 1968. (It’s a generic term) But that was an electromechanical game, with physical moving targets, and a game for the commercial circuit to boot– Sega didn’t sell anything to the masses in those days. So it was up to Nintendo to package the concept in a nice beige box that you could bring home.

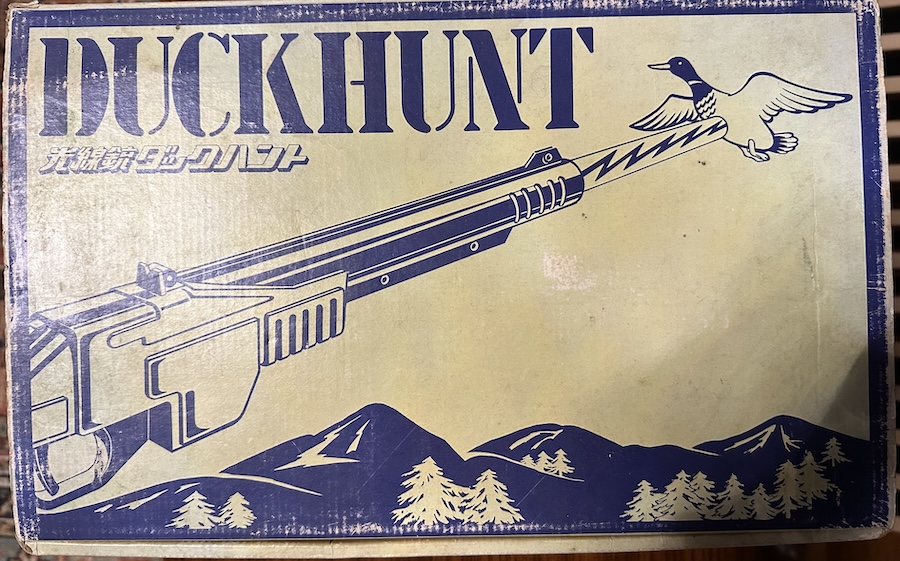

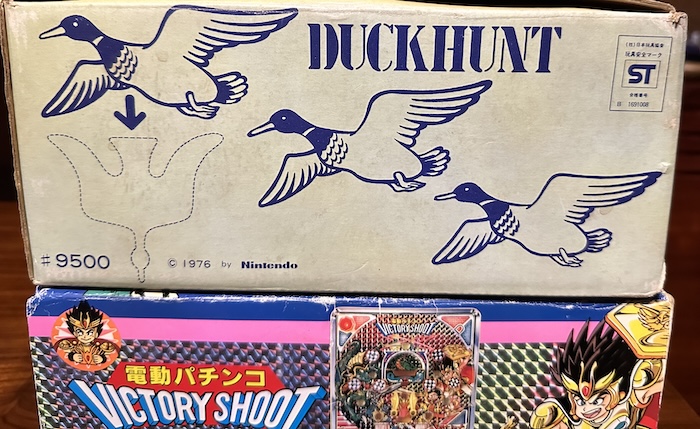

Notice that text below the English text? That text says 光線銃ダックハント, “ダックハント” being simply “Duck Hunt” in katakana, while “光線銃”, kousenjuu, is the Japanese term for “ray gun”. For Nintendo, kousenjuu was a series of light gun toys, but they were not always intercompatible– for example, Duck Hunt required the specific gun it came with. Even the Famicom Gun was eventually sold as part of the kousenjuu series in Japan. (And it was the last)

And that is one serious gun. It comes in two pieces because it won’t fit on its own. The rest of the box is taken up by the projector.

Just to drive home the point of how big the gun is, here it is compared to the “I can’t believe it’s not a Zapper” I used in the lightguns on LCD post and the Famicom Gun. It’s longer than the two of them combined. Plus, being from the 1970s, no attempt was made to make this look like a toy. Don’t carry it anywhere around your local cops, at least here in the US.

The projector takes four “D” cell batteries, which it refers to as UM-1, and the gun takes two “C” cell batteries, which it refers to as “C”; I guess Japan was in a period of transitioning between the two standard types at the time. The projector power switch literally just pushes down on the D cell batteries; this is a very mechanical device. (This also means the motor might go on for a second while you put the batteries in, don’t get startled like I did)

And that projector raises the question: is this a video game? The first definition I find is:

An electronic game played by manipulating moving figures on a display screen, often designed for play on a special gaming console rather than a personal computer.

And this manipulates moving figures (the ducks) on a display screen (the projector). Sure, it’s a purpose-built projector, but a Game & Watch also uses a purpose-built screen. And sure, it’s a mechanical device, no CPU or software here, but hey, an early analog Pong console doesn’t have a CPU either, and are we going to be that biased against mechanical logic?

And this is where the blog post takes a sudden turn for the worst. If you just want to read more about the Nintendo mechanical Duck Hunt, check out Before Mario. They even have a video and a technical breakdown. If you want to see the struggles of Nicole on her web log, well, keep reading.

Quack goes the weasel

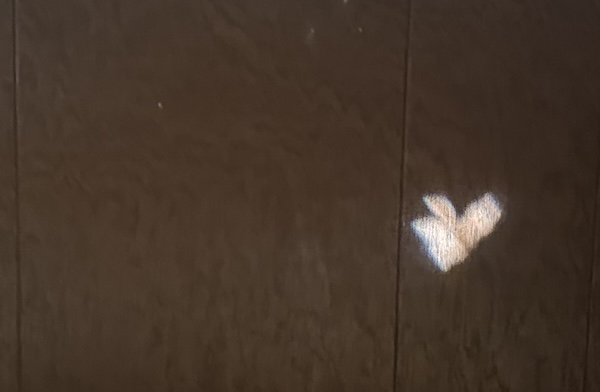

Once you turn on the projector and point it at the wall, you see a duck.

It’s a quite well-animated duck, flapping back and forth, and moving on an unpredictable course. (Actually, the unpredictable course is, like Blip, controlled by internal gears on a complex but predictable pattern) The light also turns on and off, presenting a duck flying up and down, disappearing before you can get too close to being able to predict it.

When you shoot a duck, the light will bounce off your wall and some of it will go back into the projector. There is a light sensor mounted on a bar over the projector output; through the magic of optics, this isn’t too visible on the duck you see on the wall, but light passing back to the projector can still be amplified and then detected. At that point, the projector will show the duck falling, as is presented on the side of the box:

But one thing I found is that I could not shoot the ducks. Now, I’m pretty bad at light gun games, and that’s been an obstacle several times on this blog. But it wasn’t just that– my wife couldn’t shoot them either, and she’s a much better shot. Plus, the gun wasn’t actually letting out any visible light at all. Now, it could be acting in a non-visible portion of the spectrum, but that was still a concern.

Taking apart the gun

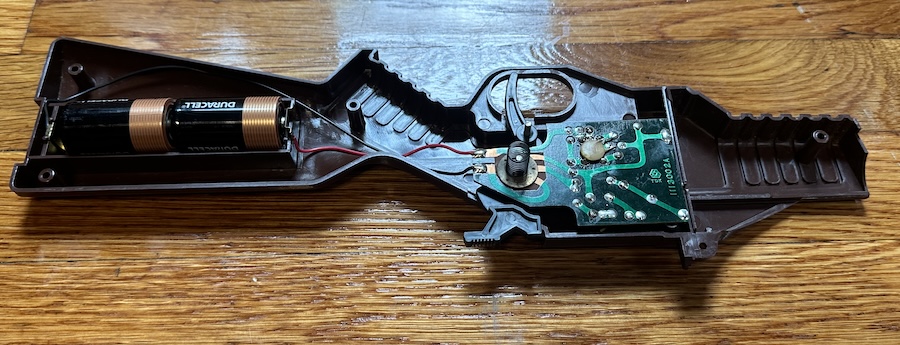

The gun is held together by bolts and little hex nuts on the other side; no screwing into plastic here, thankfully.

It’s a little bit more complicated than the Famicom gun inside here. Before we flip over the PCB to see the component side, let’s take a look at that circular mechanism.

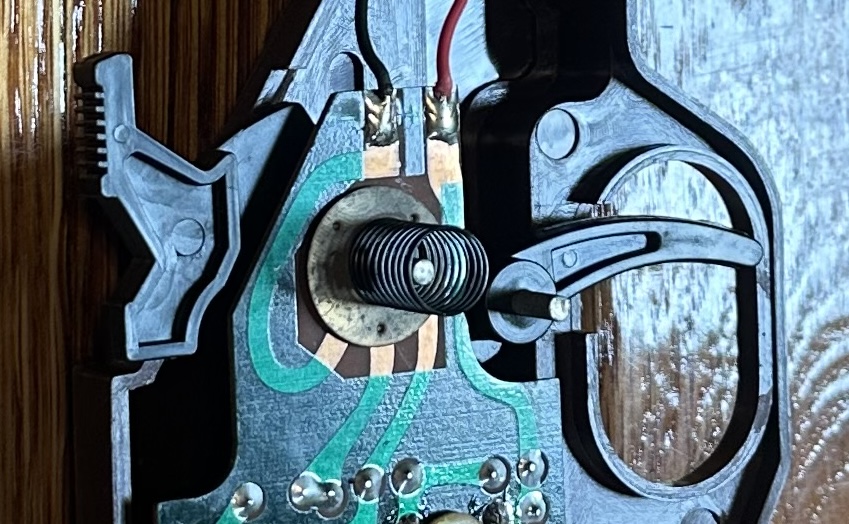

A punched metal disk has three little points, and a spring to keep the position accurate. When you cock the gun, the position of the three points changes, changing how the circuitboard is connected, and then when you fire the gun it snaps back to its regular position. Keep this in mind when we look at the circuitboard.

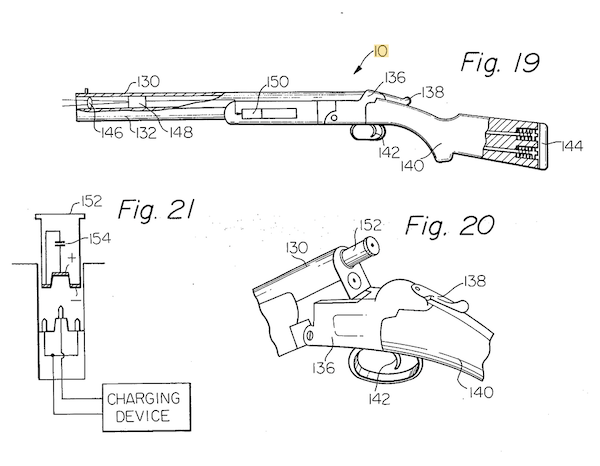

As you can see, the circuit is basically set up to charge the capacitor, and then release the voltage across a small flash-bulb. We can snag some documentation on it from the patent to confirm. Unfortunately the patent also mentions that the gun must fire a predetermined signal, so I can’t cheat by shining a light into the projector.

Unfortunately, my best guess here after checking out all the connections is that the bulb is dead. And this is where I’m stuck. So I’m going to ask anyone reading this: I know my blog posts sometimes get traction, if you happen to know a part number for this bulb, or where I could find a replacement, I’d love to try to get this gun back up and working. But for now, the ducks can keep flying indefinitely. Mocking me. At least that stupid dog isn’t there.

Leaded Solder suggested I actually give the dimensions of the bulb, which might be useful: 3.3mm diameter, a hair over 27mm long. Good thought.

A series on: Lightguns!

Focusing on the classic Duck Hunt and other Nintendo titles, with a look at how to play them without the original CRT hardware.

- Yes, You Can Use Lightguns on LCDs-- Sometimes — If your 8-bit lightgun nostalgia is only for the Master System, feel free to sit this one out.

- Yes, You Can Play Duck Hunt Without a Television (but I can't) — For those willing to take the definition of 'original hardware' way too far. And can help me fix a 1970's children's toy.