Fixing my Yamaha Electone ME-50: An FM Synthesizer Home Organ from 1986

The home organ is, at least in my home of North America, a dead market, mostly because synthesizers can do pretty much anything the old beasts could. Nevertheless, because I am that kind of person, I have a 1986 Yamaha Electone ME-50, which I’m not very good at playing; I won’t subject you to that though. This old beast needs some maintenance, and we’ll do that.

Home organs

The famous pipe organ is among the oldest of instruments, but most people wouldn’t want one in their house, due to having all the pipes take up room and needing to run the bellows and whatnot. This changed in the 20th century, mostly because of electric organs like the Hammond organ; now, the “King of Instruments” could compete with the most popular home keyboard instrument, the piano. The “spinet” style of organ was developed with smaller keyboards (called “manuals” on an organ) and a shortened pedalboard; this Electone ME-50 is a pretty late example, as home organ models started to rapidly dry up on this side of the ocean in the 80’s and 90’s. Yamaha’s newest models, like the still-sold Electone STAGEA family, aren’t sold in the US or Canada anymore.

The Electone ME-50, unlike most home organs, doesn’t try to look like a vintage piece of furniture with wood; it is unapologetically plastic, and unapologetically a product of the 1980’s. Like most later home organs in the IC era, it boasts a whole number of autoplaying features, including a sophisticated rhythm generator, automatic chord playing, and auto bass; all so thoroughly promoted that none of the saved registrations even let you use the single octave worth of pedals to play bass without customizing.

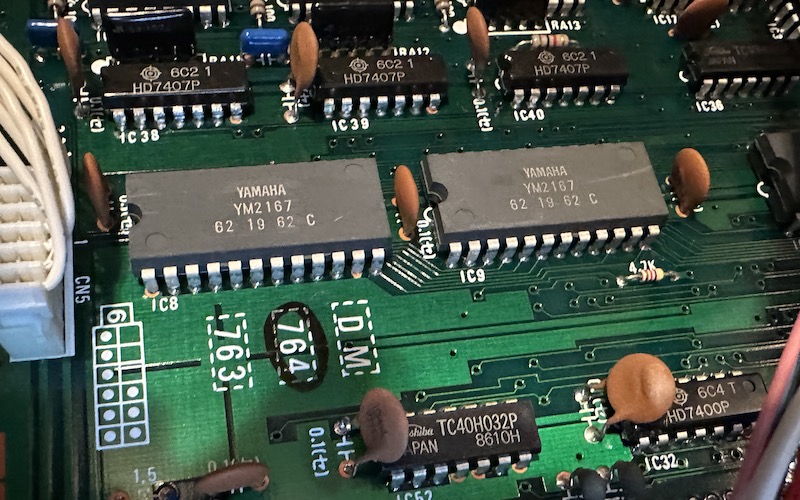

Those registrations are the big selling point of the Electone ME-50 over its smaller-numbered siblings. The ME series features a huge number of instruments; plenty to choose from on the panel, but also a complex “multi-menu” system to add even more. That’s because this is definitively a product of the FM synthesizer era: headlined by two YM2167 “OPP2” synthesizers; these are a descendant of the YM2164 used in the DX100 synth, which offered four-operator FM synthesis, eight-note polyphony. This particular chip I believe is exclusive to Electones.

It’s worth noting that the top and bottom orchestra voices only have seven voice polyphony. Presumably, Yamaha took one voice from each chip and gave them a unique voice capability, assigning one to the bass pedals (thus making those monophonic), and to other to create a “solo” voice on the upper manual, which is also monophonic, but plays on top of the polyphonic orchestral voice, giving you a taste of additive synthesis. Thus this Electone is much more limited than the typical pipe organ with how many instruments it can play at once, but its instruments are fairly sophisticated.

The accompaniment and rhythm features are quite sophisticated on this organ, though I personally don’t use them as much more than a spicy metronome most of the time. These are provided primarily by the YM2160, the OPCW2, which I believe was also used in some drum machines. Don’t confuse it with the YM2610 used in the Neo Geo; that’s a completely different chip.

I guess so this post doesn’t have no music, here’s a simple riff I made for a win music in Aspect Star 4, using pretty much only the stock rhythm machine and auto-melodies. All I did here was choose some chords on the lower manual and let the machine go to work.

Unfortunately, my particular Electone ME-50 struggles to save its instrument registrations when powered off. Much like a number of PC Engine add-ons, Yamaha chose to use a supercapacitor rather than a battery to store presets. Supercapacitors usually last longer than batteries do, but they too can fail. Since I like to play with the pedals, this makes it slightly harder to get started as I have to reconfigure everything on bootup.

Also, while I’m in there, I need to do a mechanical fix; this C key on the lower manual is drooping. It still plays, but it’s clearly lacking the springback effect the other keys have. Let’s get that now before it gets stuck permanently pressed or something.

Supercapacitor action

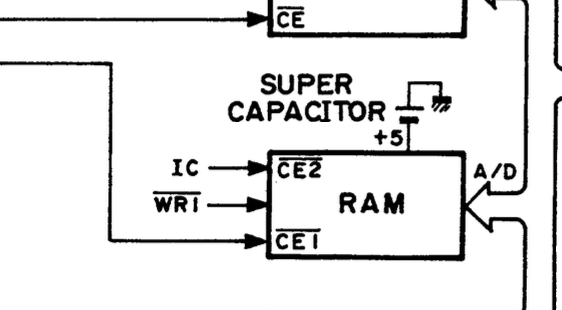

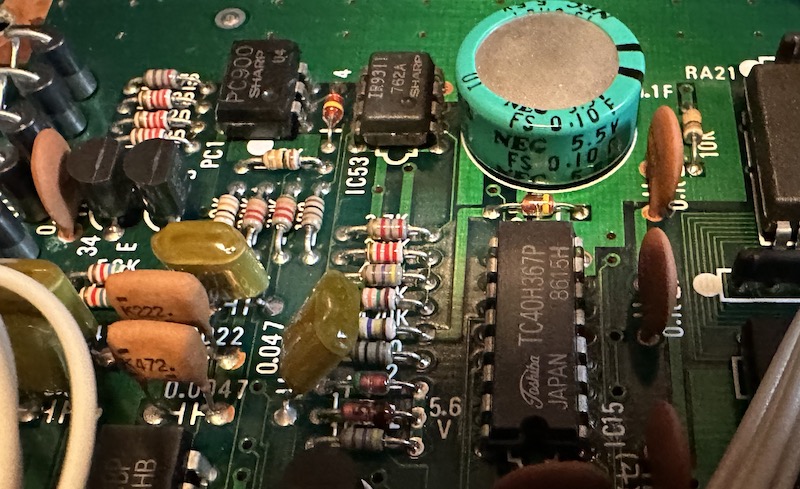

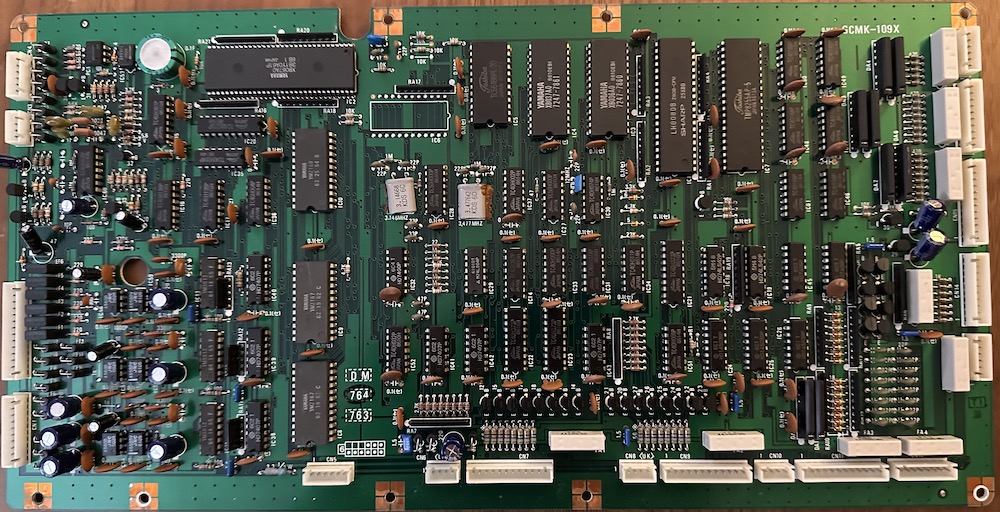

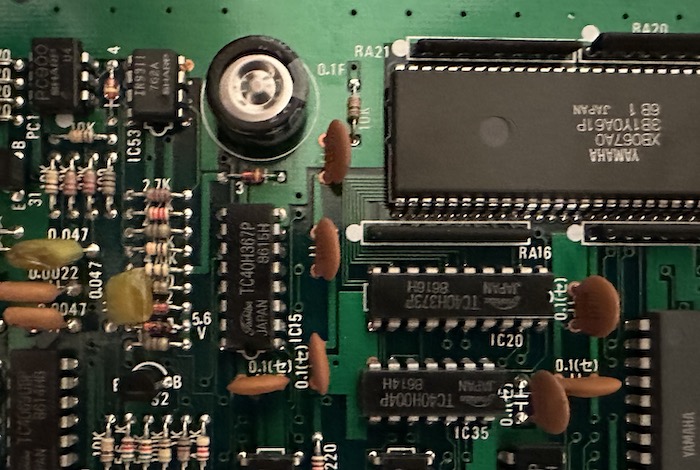

The Electone ME-50 has to interface with synthesizer chips like a computer would; so no surprise, it is an eight-bit computer. It’s got a 3.477MHz Toshiba-made Z80 and 2kiB of RAM. The supercapacitor sits between that RAM and its 5V power line, keeping the RAM alive when the system is off. The manual claims this should last at minimum a week; for me, it’s lucky to last a day.

A supercapacitor is just a capacitor with a high capacitance. You might note that the “farad” is one of those units that are rarely seen in their full form; a whole farad is a lot of capacitance, which is the ability to store charge. But that’s the sort of thing you’d need for a supercapacitor: enough charge is stored that it can stay charged for a long time without a power source “topping it off”. In theory, that also makes a supercapacitor dangerous, but in this case it’s only at 5V.

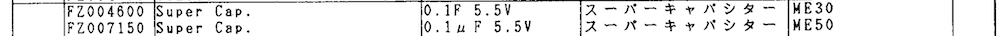

To replace the supercapacitor, we need to know its capacitance. And that’s where we hit our first snag. I happen to have a service manual for this (for some reason, vintage home organ service manuals seem to be one of those categories where some companies guard their copyrights still, though I’m not sure if Yamaha does as well), and I figured it’d be easy to look it up to buy a part without having to open the organ twice.

The ME-30 and ME-50 are very closely related, and share a service manual. The board with the supercapacitor is shared, but some components are not present on the lower-end ME-30. This appears to be one where the two differ.

But this is confusing– 0.1uF is a very common capacitor value, but it’s not exactly a supercapacitor value. One feature the ME-30 is missing is that ability to save registrations, so it doesn’t really make sense that it’d need more charge to save its RAM. And so because I don’t trust the service manual, it’s time to crack it open.

Disassembly

The easiest part of taking apart the Electone is removing it from its stand. It’s held on by just four wingnuts. A subtle cable in the back leads to a detachable connector; this connects the organ to the pedals, the speaker, and the expression pedal (on organs, this controls the volume).

Without that attached, the two-manual portion of the organ is still an entirely viable instrument. Of course, you’ll need to use the ports on the back to connect up an external speaker and expression pedal, and you’ll lose the pedalboard, but portable “combo” organs of this style were still popular in the 1980’s, so maybe some people preferred the organ to sit this way. It even has feet on the back to hold it up.

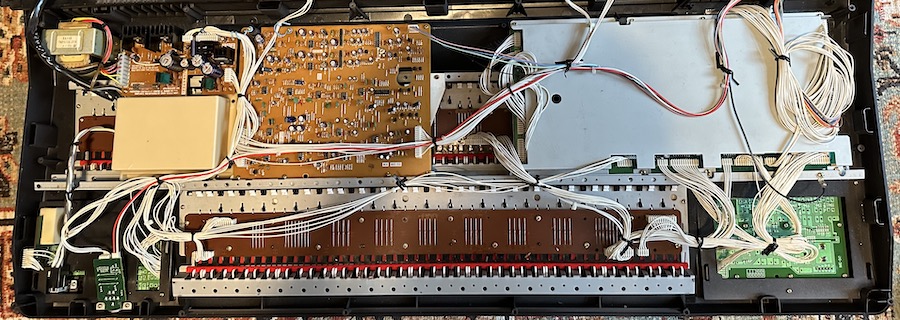

At this point, flip it over; that’s why this photo is on carpet rather than my usual hardwood floor. I removed the potentiometer knobs even though there was no reason at all to do this; this opens from the underside, and I don’t need to touch the control PCBs.

The inside is pretty intimidating; by organ standards miniaturization has progressed massively from the machines of just a decade before, but there’s still a lot to deal with. The computer, including the synthesizer chips and supercapacitor, is all underneath that large metal shield in the top right. Let’s not open that yet.

Key repair

I’m suddenly very happy the lower manual is the one that needs repairing, because getting to the upper manual looks like a nightmare.

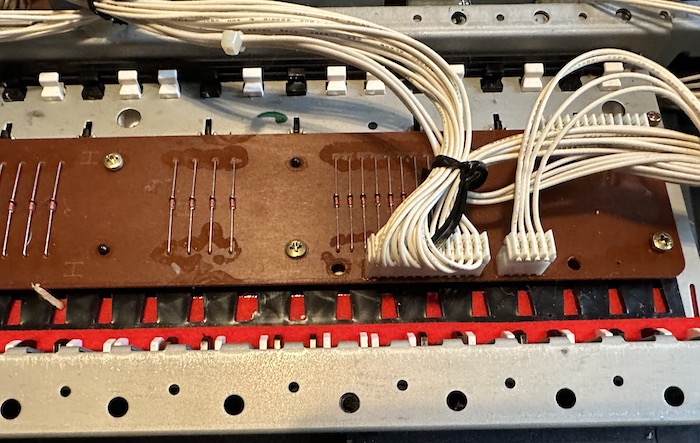

The interior may be intimidating, but this was also clearly hardware designed to last and to be repaired; all the interboard wires are connected with detachable connectors, and the key mechanism is held together with screws. You can see that it’s read as a matrix, like, well, a keyboard, with diodes to allow for full n-key rollover. That’s very important on an instrument.

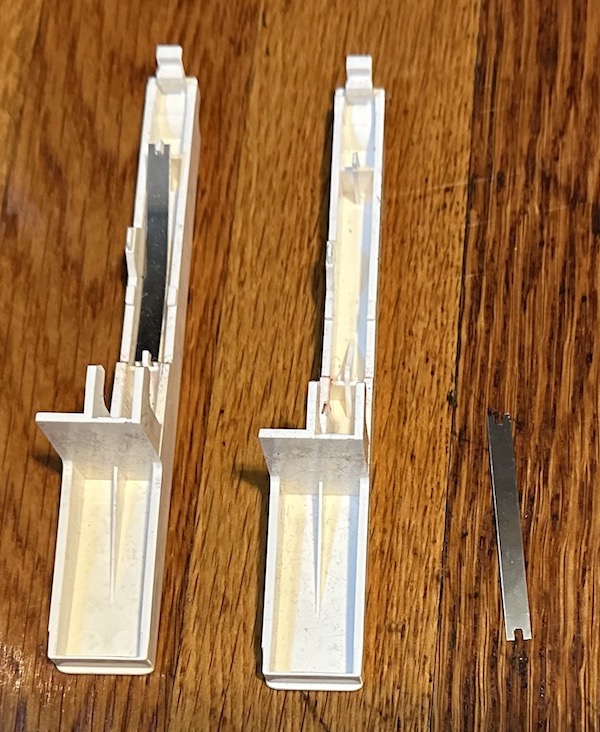

There was no need to disassemble the circuit boards to remove the key; in fact, the rubber strip in the back is all that holds them in. This isn’t to say that I started to disassemble them anyways; I took out the manual, but it’s possible this repair could’ve been done with careful manuevering.

The keys have a metal leaf spring inside of them, which provides the return force. This surprisingly doesn’t sit on tabs or anything; the sheer force of the spring holds it in place. Or it should; as you can see, the spring fell off the key that was drooping, and so it only was being held up by the felt of the keyboard. Thankfully the spring was just sitting inside the mech, so it was easy enough to shove it in and put it back on, and it’s as good as new.

Service manuals never lie

That’s one problem sorted. The other problem is that supercapacitor. I wanted to remove as few wires as possible this time; I still play this organ as my daily practice instrument, and will need to order a part, so I know this is going back together before the final repair. We’ll deal with removing that circuitboard. Thus there aren’t many pictures, because I was delicately balancing the shield and a bunch of still-connected wires on the edge of disaster. But I got what I needed:

The supercapacitor is indeed 0.1F on the ME50, not 0.1uF. My only guess as to why is that the ME30 is the one with 0.1uF, and that’s just because it uses the same circuitboard but doesn’t have saved registrations; but I’m not really sure without seeing an ME30. In any case, we’re now armed with what we need to replace it.

I took this revelation with grace.

Take that, overworked 1980’s organ technician who put together this service manual that I’m lucky to have. Actually, this might not even be their fault; maybe it’s that Xerox bug again.

Take 2

Opened the machine up a few days later once the capacitor came in. Here’s a better view of the main board; this is shared between the ME-30 and ME-50. That empty socket is listed as being a 2kiB ROM chip, and isn’t listed in the service manual as being system-specific. Perhaps its code was consolidated with another chip in a revision?

In any case, removing the capacitor was a bit of a pain due to the thick leads, but I got it out, and a new Panasonic capacitor in. It’s a little smaller than the NEC original, but the leads have the same spacing, so no problems there.

And so far so good! A bit of a scare on the first test and got no sound, until I realized that I had forgotten to reattach the speaker. And so far, no lost registrations.

Some other options

So let’s say I didn’t want to do soldering so couldn’t replace the supercapacitor, and was desperate to save my registrations one way or another. Thankfully, I wouldn’t be out of luck.

I’ve shown off this organ’s MIDI capability before, in my shaggy dog story of looking into the Sega ST-V MIDI out capability. But right next to those MIDI ports are two 3.5mm cassette jacks. This is an 8-bit computer, after all, so of course it can save data to and from cassette. (On the ME-30, this is the only way to get data out, but the ME-30 can’t save registrations, so it’s only for the sequencer there)

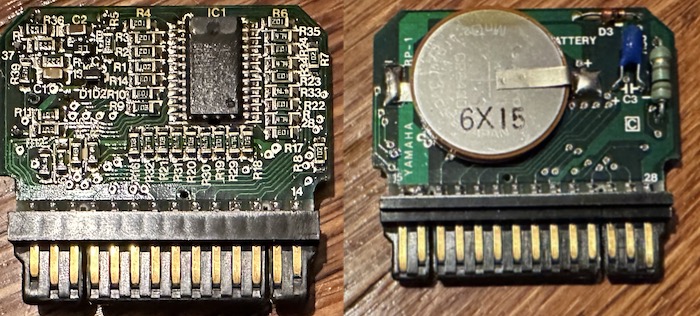

Yep, like many 8-bit computers, this one takes cartridges. Registration Pack 1 (RP-1, not to be confused with rocket fuel) is a rewritable RAM cartridge. I took mine apart, but I actually recommend you do not, as it’s held together with glue so it doesn’t ever go back together as well as it did.

It’s just a battery-backed RAM cartridge. Since it’s only designed to store data, it has only RAM; I believe Yamaha did sell pre-populated registration packs with ROM. These were supported by multiple Yamaha organs, but as the manual warns, you can’t move registrations from one organ to a different model; after all, they don’t have the same synthesizer chips.

The RAM is just a standard surface-mount Mitsubishi part, 2kiB of static RAM. Unfortunately, the battery in this RP-1 is completely dead, reading at 0V. So I guess if I wanted to use this I’d still need to do some soldering, just like with the supercapacitor.

I’m hoping the current repair lasts me the full length the organ remains in my house. I’m not sure how long that’ll be, though. Once I improve, I’d really like to expand out of spinet-specific repertoire, and that might require things like “full-sized manuals” and “an actual pedalboard”. Or maybe I’ll go crazy and get a combo organ. We’ll see. Gotta practice enough to justify that.

As for the historical standpoint, there is something almost ironic about the FM Electones: FM synthesis, in the form of the much more popular DX7 and DX100 synths, played a big role in wiping out the organ from popular music. Digital synths could be made highly compact, and so would also wipe out the need for a living-room sized multi-keyboard behemoth to get a wide variety of instruments and rhythm machine capabilities. And so be warned, Electone ME-50: you carry the seeds of your own destruction.