It's a bird, it's a plane, it's Super Cassette Vision

The Epoch Cassette Vision was a moderate success. But in 1983, that all ended, when Nintendo and Sega released new consoles, which had more advanced hardware that allowed for better graphics and games stored on ROM. Epoch went from dominating the cartridge-based game market in Japan to a distant third practically overnight. But it’s not like they were unaware of the issue with the µPD777 they had tied themselves to. In 1984, Epoch launched their last, best hope at regaining their video game success. Imagine, if you will, a cassette vision: but super.

Full of surprises

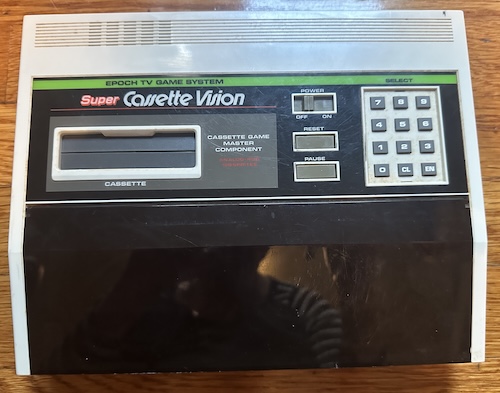

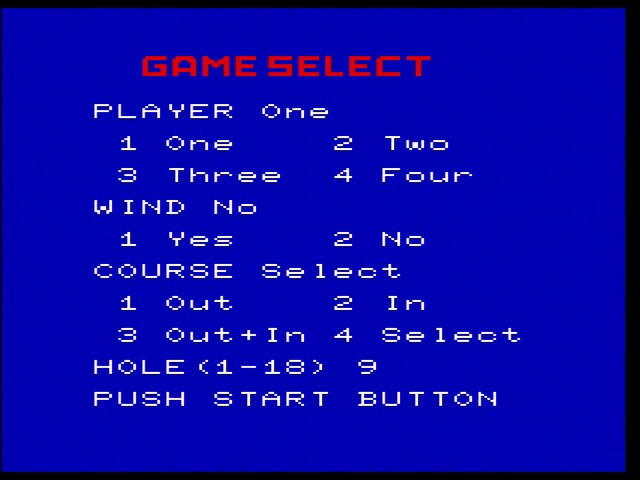

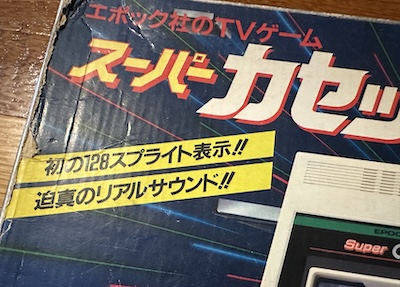

The Super Cassette Vision surprises from the top corner of the box. That’s right; this is the first known video game console that actually advertised the capability of RGB output. Sure, computers like the Fujitsu FM-8 had it before, but this is an era where neither the Super Cassette Vision nor neither of its competitors at the time even had AV output.

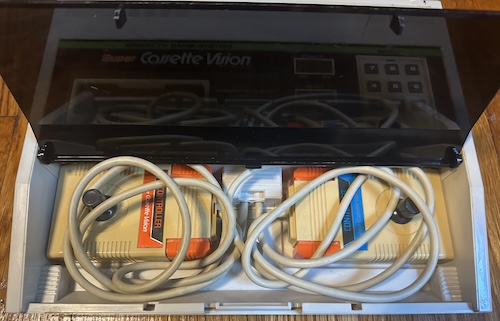

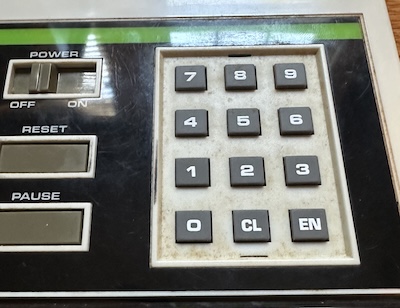

In terms of appearance, the designers of the Super Cassette Vision seem to have been taking a Japanese approach to the Atari 5200, with its controllers (hardwired, unfortunately) stored inside the console. It also features a numeric keypad, which several American consoles of the period had; instead of putting one on each controller, it just puts one on the console. This provides some extra buttons, since the controllers, like Sega’s SG-1000, have only two. (But unlike the SG-1000, you get two controllers wired in, just like the Famicom)

And yeah, these controllers are pretty bad. They’re also matrixed, which makes it a bit hard to just wire in a port for a Master System controller (see a schematic here); otherwise I’d have tried doing just that.

What makes it so super?

For a CPU, the Super Cassette Vision goes with a 4MHz NEC μPD7801G. This is an off-the-shelf microcontroller, comparable enough to the Z80, sold by NEC with an internal ROM, which is used as a basic BIOS and some helper functions for games. This might be the first time this was done in the Japanese market; the Othello Multivision had a built-in game but the BIOS wasn’t available while other games were being played. But the ColecoVision had Epoch beat back in 1982. Having a BIOS means you can have a screen that shows up when you have no game plugged in; no snail maze here, though.

The Super Cassette Vision’s video is powered by the EPOCH TV-1. Unlike the Cassette Vision, this wasn’t done by Tetsuji Oguchi’s team at NEC; by this time, they had moved on to the graphics behind the NEC APC series. Instead, it seems to have been designed in-house by Epoch, or possibly by another contracted firm.

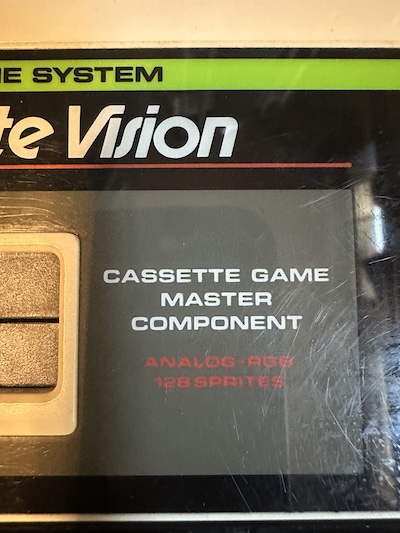

Takeda Toshiya, developer of a Super Cassette Vision emulator, provided some additional information on the graphics compared to the box, which already brags about its 128 sprites, as does the console itself, in hard-to-read red text.

- 128 sprites, each 16x16 tiles and monochrome.

- 64 of these are specialized for use as background objects, and 64 for use as moving sprites. These generally deal with how large the sprite is and whether it can combine with neighbors to act as a single sprite.

- Background screen, with several modes:

- Tilemap, using a tile ROM that’s built into the Epoch TV-1, not customizable

- Directly-addressable graphics using 8x8 sized blocks in any of the sixteen colors

- Directly-addressable graphics using 4x4, but only one pair of colors can be used for the whole screen

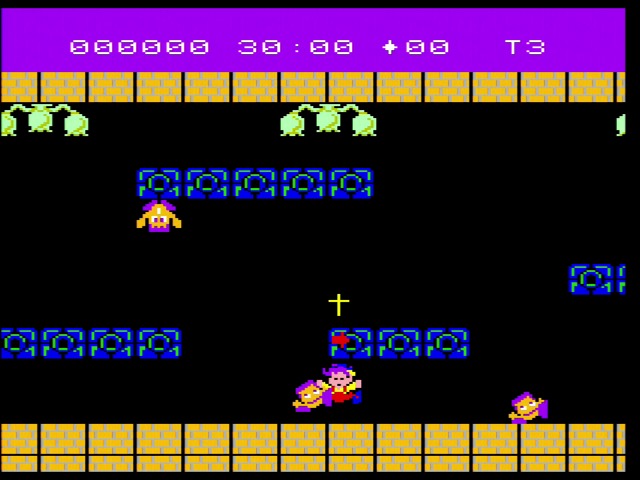

This makes for a very different set of limitations than other 8-bit consoles. The sprites are very advanced; compare to the SG-1000’s monochrome sprites that can only have four per scanline. The Super Cassette Vision appears to have effectively no sprites-per-scanline limit. This sounds a lot like the Cassette Vision hardware, which was also based around movable patterns that were essentially sprites, and probably helped Epoch’s developers, who were now freed to develop more than one game at a time. Take a look at the many moving objects in launch title Astro Wars; we’ve come a long way from TV Vader.

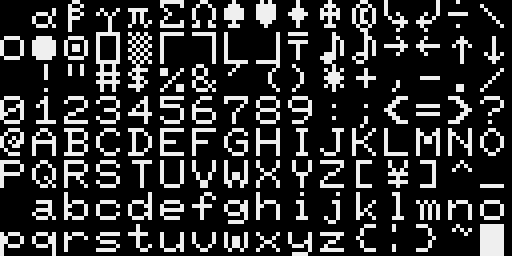

But that tilemap is far more limited than what the NES or even the SG-1000 could do. Having a directly-addressable color mode can be useful even with large pixels; Nintendo did well with their Popeye hardware; but the size in question is very limiting. Having a fixed tile is convenient for fonts, but pretty much nothing else. Every Super Cassette Vision uses the same narrow pixel font (reminiscent of the VIC-20 to my eyes); now you know why.

That tilemap has been extracted, so behold, every character that can be displayed by the Epoch TV-1. These really aren’t intended for anything more than text; there’s not even enough space for either of the Japanese syllabaries, just the upper and lowercase Latin alphabet.

Super flat

The audio on the Super Cassette Vision is a disappointment. Sure, the NEC µPD1771 appears to be a sound chip with an impressive pedigree, a sixteen-bit microcontroller with onboard ROM and RAM designed for wavetable sound, and can also play back PCM samples. But this is the same chip Epoch used in their contemporary LCD games. That is to say, it’s not really designed for music, like was becoming common in console video games.

There is just one channel, which can be a tone (the wavetable sounds using the onboard ROM), noise, or sample playback. Even the Atari 2600 and the Epoch Cassette Vision had at least two channels; this means that the Super Cassette Vision can’t even play a single channel of music and a simultaneous sound effect. Unfortunately for Epoch, 1984 is pretty much the last moment in history anyone would consider this acceptable for a game console. Listen to what it does to poor Mappy.

This is actually one of the best Super Cassette Vision games, sound-design wise. Fairly sophisticated waveform, but just one channel is very painful. Sadly, this version of Mappy came out years after the Famicom’s release.

Can it do Mahjong?

I’m going to outright say it: the original Cassette Vision can’t play mahjong. Especially not Japanese riichi mahjong, where the rule of furiten requires that you have full access to see each player’s separate discards at all times, as well as your full 14-tile hand. Even if it had the sprites (it doesn’t), it doesn’t have enough pixels on the screen.

Now, you might say, who cares. But Mah-Jong was a big deal for Nintendo. It showed up in the earliest Famicom commercials. It was one of the top selling games on the console. It helped get the Family Computer into houses by giving adults something they could play. Sega’s SG-1000 too got into the Mahjong game quickly. And in that context it’s not a surprise that Epoch got in quickly with Super Mahjongg once they had a capable machine.

Well, I’m here to say that the Super Cassette Vision can do mahjong. It doesn’t look as good as Nintendo’s, and it can’t fit your whole hand on one line, but the less detailed tiles aren’t that far off from what Nichibutsu was putting out in contemporary arcades. Minus the girl. Where’s my 8-bit girl, Epoch?

One thing that’s interesting here is that the tiles slide around smoothly as you play them. Nintendo’s Mah-Jong can’t do that, because Nintendo’s tiles are part of the tilemap. Epoch’s tile map can’t do that, so these are all sprites, and as sprites, can move much more freely.

The Super Cassette Vision’s Super Mahjongg also uses the button grid for making “calls”. Nintendo is forced to resort to having a menu of calls. In practice, this doesn’t actually matter that much. Apparently, it came with an overlay so you could have the calls always labeled on your console, but though my copy was sold as complete in box, it didn’t actually have the overlay. Caveat emptor.

Of course, the Super Cassette Vision probably doesn’t have the graphical resolution for the actual four-player version of mahjong. We would’ve had to wait for the Ultra Cassette Vision for that.

Can it do the Mario?

So, as most reading this probably already know, in 1985 Nintendo went and changed the video game scene. Super Mario Bros. was not only the best-playing platform game ever made up until that point, with smoother more enjoyable physics, it was also a whole new scale of gaming. A smooth side-scrolling platformer with a whopping 32 long and mostly-unique levels, at a time where single-digit number of single-screen levels was still something you could put on store shelves without being laughed out of the room.

Super Mario Bros. proved a very hard target for competing hardware to match. But while the SG-1000 had no scrolling whatsoever, producing clunky 8-pixel-at-a-time scrolling in Wonder Boy (which still managed some impressive visuals for its console), the Super Cassette Vision should have an edge here. The Neo Geo didn’t have smooth scrolling, but its sprites could move freely, and that was good enough.

Y2 Monster Land is usually listed as Epoch’s contender for Super Mario Bros., and well, it definitely can scroll. Plus, at 128kiB, it has a bit more space than Mario’s game.

Much like how the Cassette Vision’s Monster Mansion used a movie monster theme to remix Donkey Kong, we return to that theme with Y2 Monster Land. (Y2 is just a strange way of writing “wai-wai”, a Japanese onomotopoeia here used to denote excitement) Epoch built on Nintendo’s large levels by creating much more maze-like stages; thankfully, you have an arrow above your head to give your directions. Plus, there are only six of them.

If you get hit, you lose your weapon. Once that happens, your arrow points to a new weapon powerup; you’ll need it. Without a weapon, you’ll die in one hit. You can collect gems to upgrade your weapon, but they’re in hidden areas.

Y2 Monster Land is not an enjoyable game, unfortunately. The water level is probably the best of them, because it avoids two major problems.

- The Super Cassette Vision controller is really bad. The buttons are mushy and don’t feel reliable; barely acceptable for Super Mahjongg, very painful for an action game.

- Jumping is also very bad. It reminds me of Micronics’ NES port of SNK’s Athena, where your jump height varies up to being as tall of the full screen, but it’s not really obvious why.

This is harsh, but Y2 Monster Land is a good example of what’s wrong with Epoch’s in-house efforts for the Super Cassette Vision and really also the Cassette Vision; derivative, with a decent aesthetic sense but no real gameplay sense.

Epoch and Friends

Surprisingly, the Super Cassette Vision got some third-party support. Well, sort-of. I’m not actually sure if all the games were done in-house by Epoch with outside licenses, or if companies like Namco (whose Mappy we’ve already seen) actually developed for Epoch. In any case, I feel like the quality level of these ports surpass Epoch’s own unique works. For example, the ports of Miner 2049er and Boulder Dash? Quite solid.

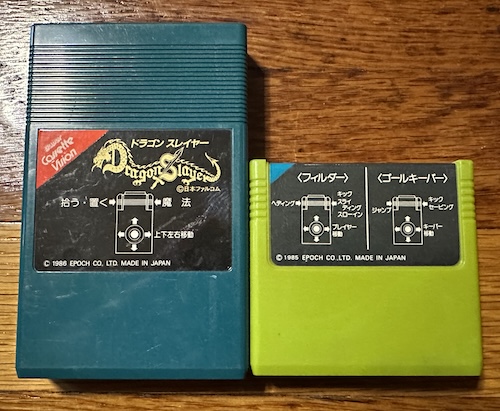

And there’s one more title that might just be the most interesting thing about the Super Cassette Vision. One of historical significance that ended up with its home console rights trapped on this sinking ship. Falcom’s Dragon Slayer.

Not only does Dragon Slayer use an extra-tall battery-backed RAM cartridge (before The Legend of Zelda), with easily-changed AA batteries, but it’s also the start of a long-running series that includes games like Legacy of the Wizard. It’s the midpoint between Atari’s Adventure on one hand and games like The Legend of Zelda, Ys, and Dragon Quest on the other. Maybe even Atari’s Gauntlet was inspired by this; I can see some similarities.

Dragon Slayer on the Super Cassette Vision is squeezed into a 32kiB cartridge (with extra on-board RAM). But that’s how much space it had on the MSX computer as well, so though the small size surprised me it’s not that big of a sacrifice.

Believe it or not, in 1986, this was probably the cheapest way to get into Dragon Slayer. The only other way was to get a computer, after all– though some of those MSX machines sold pretty cheaply. Unfortunately, 1986 is also when games inspired by Dragon Slayer started to flood the Famicom, many of these with a much more pick-up-and-play mindset too, like Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda.

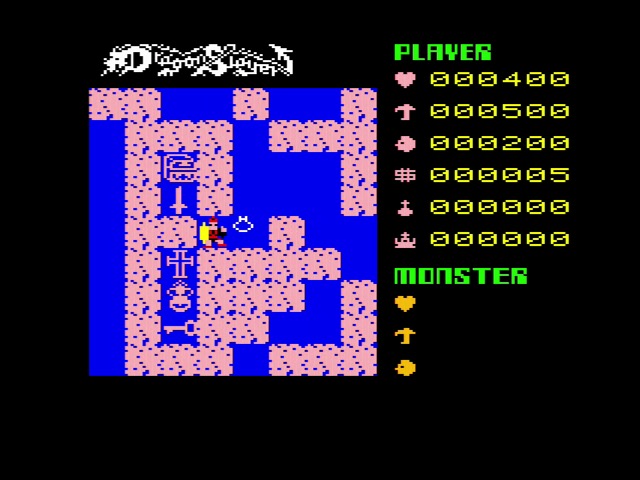

It’s a very faithful port of the game. The color scheme is a bit odd, and it’s a bit opaque, but once you get into it there’s a rhythm. It’s really all about the grind of powering yourself up, though, which definitely feels dated.

You will pay the price for your lack of (Super Cassette) Vision

The Super Cassette Vision is remembered as the third-place console in a market that didn’t even really have room for two. In the mid-1980s, the Famicom was a mega-hit in Japan and no one could touch it. Even Epoch eventually gave in and made games for Nintendo’s system. At least the Super Cassette Vision had some interesting hardware to look back at. And with a graphics system based around sprites and heavy advertising of tech specs, Epoch walked so SNK’s Neo Geo could run.

Do I recommend you get one? Eh, only if it’s to replace the controller. That thing really lets the whole system down.