The RCA Studio II in Living Monochrome

Remember the RCA Studio II? A chipset with a fascinating history and enthusiast cred put into the service of the most disappointing game console of 1977. But mine didn’t work at all– well, that hasn’t changed. But thanks to partlyhuman (Roger Braunstein), creator of the Floopy Drive, I now have two RCA Studios II. One of them might even work, so now we can try out the games here.

But first

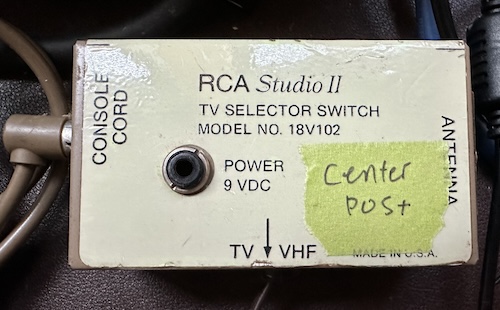

I mentioned in passing in the RCA Studio II post that the console was powered by its RF switch, but I didn’t have the switch then to show off. Now, I do:

One thing you might not know is that generally, these switches have no smarts at all; the RF modulator inside the game console is what actually modulates the signal onto the channel. The switchbox’s job is just to provide a connection to the TV, and allow the user to also watch TV sometimes. Most of the time they’re all interchangeable.

But this one’s an exception, because it provides power over the RCA cable. (Of course RCA would do a clever thing with an RCA cable) It also expects that power through a 3.5mm jack. Roger included a 3.5mm to barrel jack adapter, so that note on the adapter is just a reminder that with the adapter this needs center-positive. 9V center-negative is way more common on old game consoles, so this is a welcome reminder to avoid me blowing something up.

In this case, the switch to go between TV mode and console mode also turns on the power to the console, which doesn’t have a power switch of its own. When it turns on it beeps for just a second– this may be a useful sign for my other RCA Studio II, where the beep stays on indefinitely.

Finally, this particular RF switch outputs to 300Ω “twin-lead” antenna cable. However, twin-lead is now not used too often (it’s more interference prone, and not as well suited to higher UHF frequencies), and by the 1990s TV antennas had switched to 75Ω-impedence coaxial cable. Twin-lead is a “balanced” connection (the two conductors are equivalent to each other), and coaxial is “unbalanced” (one conductor carries the signal and the other is a shield), so we need what’s called a “balun”– a small transformer that goes from balanced to unbalanced.

And we have picture! Yep, the RCA Studio II does indeed boot to a blank screen– and now you also understand why I always go for video mods on these RF-only consoles when I can. My terrible RF2AV box is having a hell of a time trying to catch even this black screen, and when there’s pictures it’s even worse– but given the issues I had with my first one, I want to go through the games before I start trying to mod this one.

Take a look, it’s in a book

To understand how to use the RCA Studio II, it’s a good idea to read the manual. Once you do, you’ll find out that the RCA Studio II contains a lot of built-in software, the only major advantage it offered over the Atari 2600 (which has none) and the Fairchild Channel F (which has two Pong-like game variants).

The creative games

These first two games have something in common: they’re the reason I said “built-in software”, not “built-in games”. (Though RCA calls them all games, so whatever) See, while video game consoles had existed in the US market since the Magnavox Odyssey in 1971, they were still a pretty niche product– there were a lot of people to whom the concept of being able to control pictures on the family television was still a novelty in and of itself.

Or at least, that’s what RCA was hoping.

Game 1: Doodle

![]()

With Doodle, you can control a single pixel with the keypad on the “B” side of the console. And because it’s a genuine RCA Studio II™, it’s a big chunky pixel. That’s RCA’s promise to you.

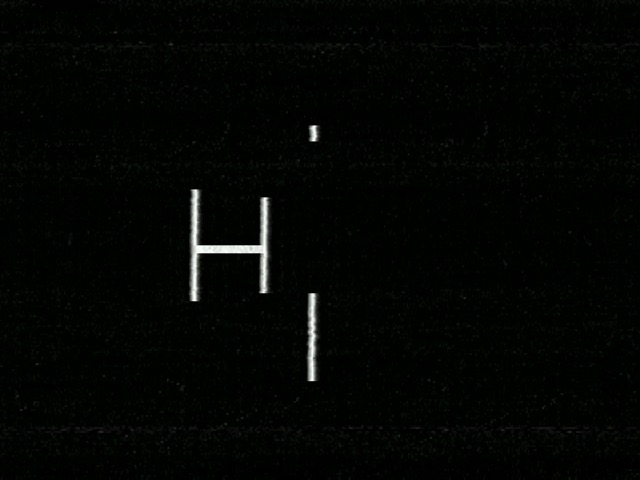

Plus, you can start drawing lines and things on screen with the “5” key to start writing, and “0” to stop. I started writing the word “HI”, but then the screen lost sync after I wrote the H, so I tried writing the I without looking at the screen.

Nailed it.

Game 2: Patterns

This is the one RCA thought was worth advertising, so it’s got to be a good one.

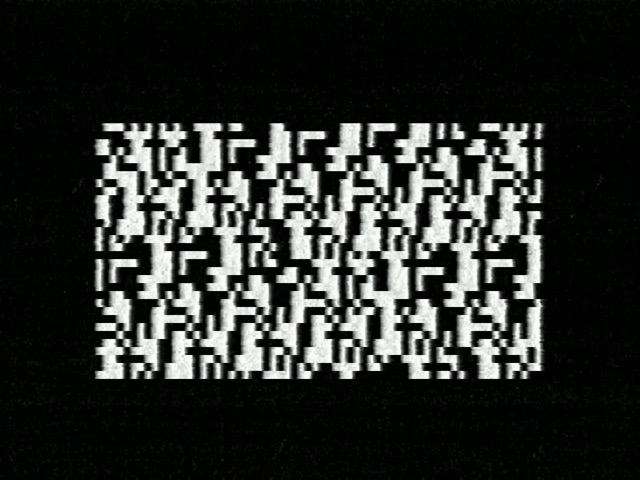

Essentially, you draw a few pixels on screen using the control pad. Then, press “0”, and the advanced-design computer inside your Studio II will take it from there, moving in various lines inverting pixels as it goes. Here’s a video of what that can look like.

Feel free to use that for your experimental music video. And here’s a shot of what that pattern looked like about a minute later.

This one is actually surprisingly fun. At least a few seconds of fun, rather than the one second of fun Doodle offers. Let’s go into the actual games.

The actual games

RCA offers built-in examples of all three genres: sports, racing, and edutainment. Truly the Studio II provides a level of gaming enjoyment that won’t be surpassed any time soon, and definitely hasn’t already been surpassed.

Game 4: Bowling

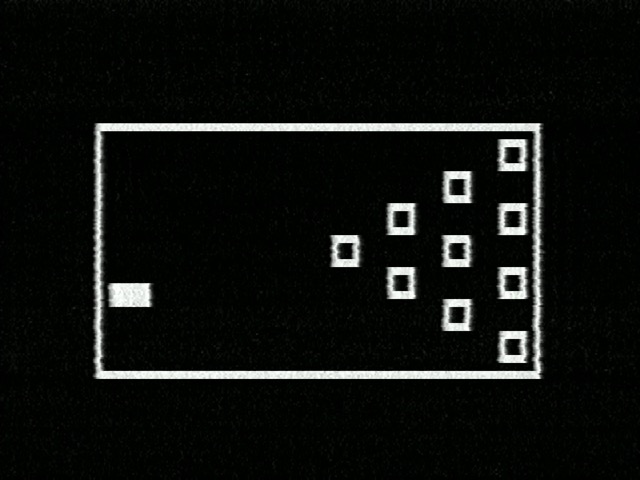

Bowling for the Studio II is probably the game that takes the most advantage of the system’s graphical capabilities, to the point where the manual recommends using it to test your television and calibrate it for the console.

And yes, the ball is square. The rectangle here is because the Studio II’s graphics aren’t synced to the game code at all. Take a look at the pseudo-assembly that RCA expected developers to use; there’s nothing to synchronize. (It does have 60Hz counters, but I don’t think anything used them for synchronization) So it’s very possible for the screen drawing to interrupt mid-sprite drawing.

Bowling is always a two-player game, just like real bowling. You have two tries to hit all the pins down; the ball moves up and down on its own, and when you click a button, you will move the ball either forwards (button “5”), or forwards with a curve upwards (button “2”) or downwards (“8”). Here’s what that looks like in action. F01 stands for “frame one”; real bowling afficionados will know that a round in bowling is called a “frame”. That’s what makes this so realistic.

I think the limited curve options is what really reduces the interest in Bowling. But the ball moving up and down might be the one of the earliest examples of the “timed button press” mechanics, which is pretty cool.

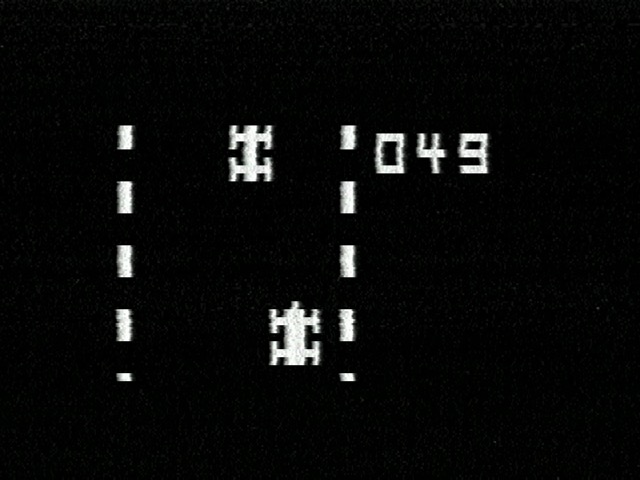

Game 5: Freeway

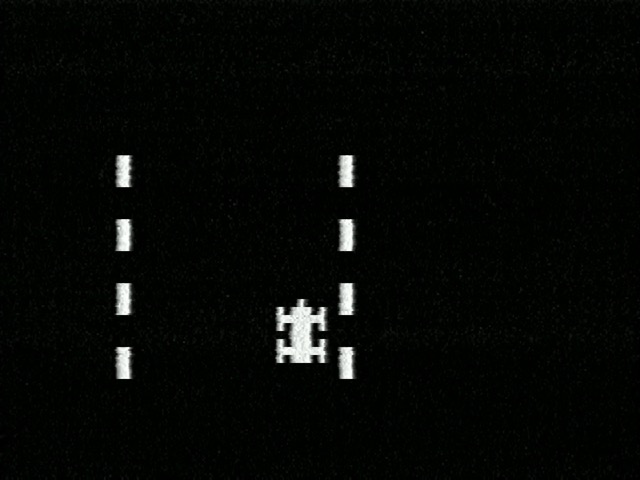

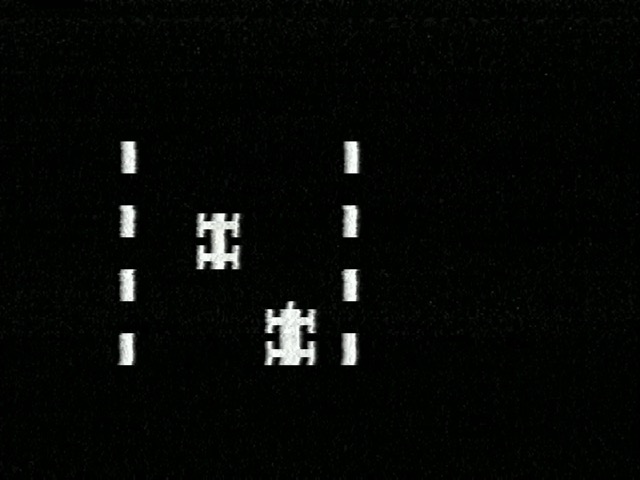

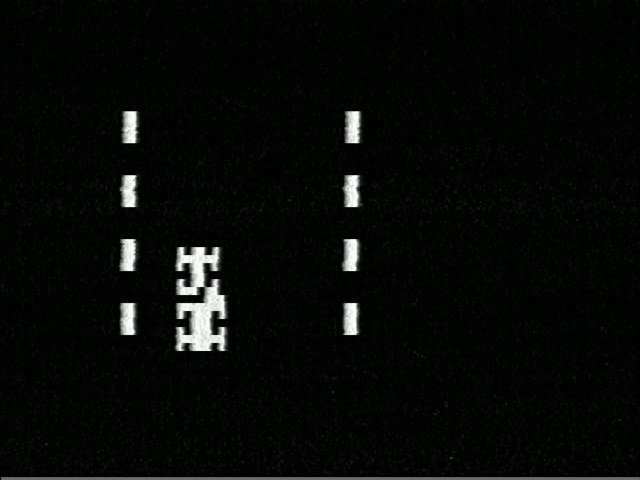

Freeway is a pure real-time action game. As the Apple ][ shows us, you don’t need a timer interrupt to do a real-time game. Freeway shows us that you also don’t need to use the full screen.

You control a car, and uniquely for the built-in titles, you use both control pads. The left one, “2” and “8” move your speed up or down, in some kind of ersatz substitute for a gear shifter. On the right one, “4” and “6” move your car left and right. It’s a bit odd that they didn’t use the left hand for driving and the right hand for doing something kind of like gear shifting, but hey.

There is one other car on the road. Your car is always at the bottom of the screen; the other car is computer-controlled, and will try to aim in and hit your car. It’s extremely difficult to dodge.

Thankfully, hitting the other car doesn’t cause you to lose or restart. This game is a pure time trial, and your goal is to get a better score. Hitting the car just causes you to slow down to the lowest speed, and for the console beeper to complain.

By the way, notice how the parts of the two cars that intersects are inverted? The Studio II’s pseudo-assembly interpreter uses XOR to implements its software sprite system, so this is what you get when they intersect.

After two minutes of this, you’ll get a score.

Freeway and Bowling both echo common electro-mechanical arcade games of the 1960s; Freeway echoes Chicago Coin’s 1969 Speedway (licensed from Taito’s Indy 500), and Bowling echoes the “Shuffle Bowling” machines of the same period. These were a common well of inspiration for video games in this period, but it really does end up feeling like RCA had never heard of the existing video games. Of the two, I think Freeway is quite a bit more fun.

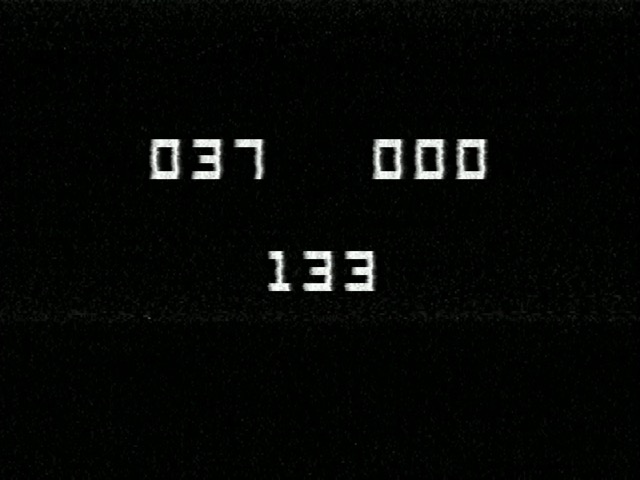

Game 6: Addition

In theory, a major advantage of the Studio II and the Channel F over the Atari 2600 is that with their bitmap screen displays, they should have a better time handling text and numbers. This should make them better for edutainment games.

Here’s RCA’s Addition. Notice there are three three-digit numbers. The top left one is the score of the left player. The top right one is the score of the right player. The three-digit number in the center is actually three numbers; your goal is to sum them up, and then press the number on the pad corresponding to the sum before your opponent does.

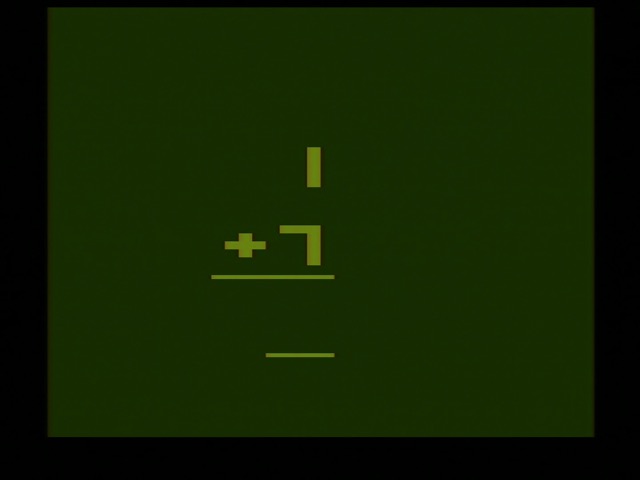

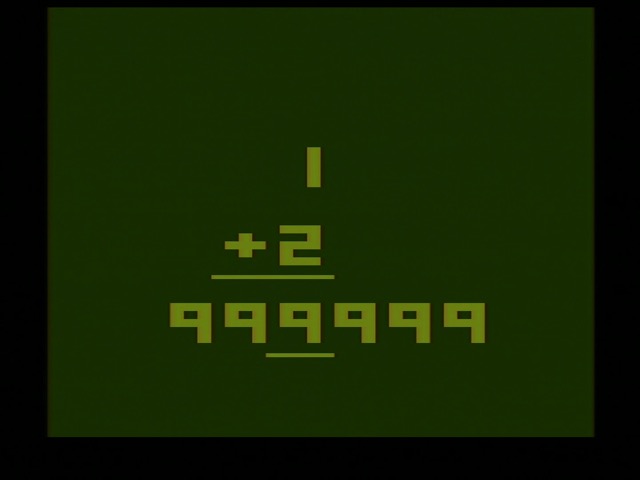

And now let’s compare it to what else was on the market, the 1977 Atari 2600 game Basic Math. Since Basic Math was sold separately we won’t judge Addition for missing multiplication, division, and subtraction. But just look at Basic Math in comparison.

Notice that while Addition requires you to read the manual to know what all its numbers mean, Basic Math makes it clear that this is a math problem by showing the addition sign and the equals bar underneath. In theory, a major advantage of the Studio II should be their bitmap screen display, but in practice the Atari 2600 can also display six numbers in a line, so does it matter?

Addition is a two-player game while Basic Math is one-player, so it does have that going for it. But honestly I’ve probably said far more than enough about these games, so let’s take a look at a cartridge. The same cartridge from the last post, in fact.

Game cartridge action

I have just one (1) cartridge for the Studio II– TV Arcade III. Archive.org has the manual. When you boot up the game console with the cartridge and press “CLEAR”, you’ll get the familiar Studio II home screen.

This is booting to the same internal firmware. However, now the buttons on the “A” keypad that previously accessed the built-in games will instead access the games on the cartridge. What did RCA do uniquely in their take on the well-treaded waters of Pong / Odyssey Table Tennis?

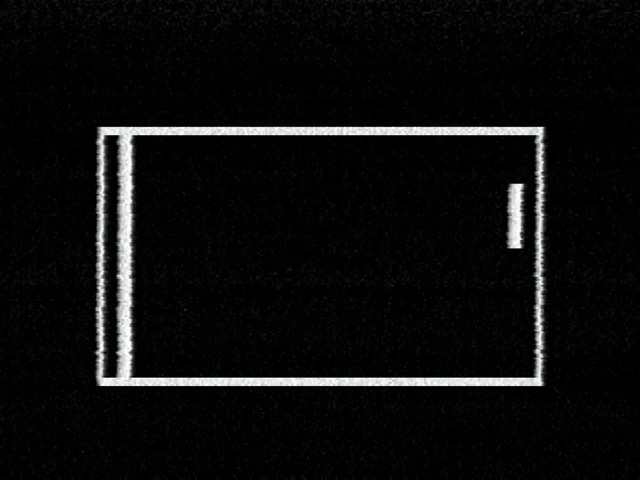

Game 1: Squash

Squash is a pretty common game on Pong consoles, but the only one in the eclectic set I looked at that had it was the Magnavox Odyssey 500, where it was called Smash. But in the Odyssey 500, it was a two-player game where two players took turns bouncing a ball off a wall.

Squash on TV Arcade III corresponds to the game that most AY-3-8500-based consoles called “Practice”; the goal is still to bounce the ball off of a wall, but only one player (using keypad “B”) can do so.

You’re really going to want to read the manual to get started with this one, as it’s a bit of a process.

- Turn on the Studio II with the cartridge inserted and press “CLEAR”.

- Press button “1” on keypad “A” to select Squash.

- Select your racquet size on keypad “B”, using 4 for small, 5 for medium, and 6 for large.

- Select the ball speed on keypad “A”, using 7 for slow, 8 for medium, and 9 for fast.

At that point, the game will start.

It’s a decent enough effort, and certainly means that I have one more excuse not to get an AY-3-8500, but TV Arcade III Squash suffers in a few ways that specifically come from being on the RCA Studio II, and not on a Pong console.

- Controls are digital. Remember Nintendo’s first take on the Pong console also featured digital controls; having a selectable speed this time is nice, but Pong is much more fun with potentiometers.

- The pixels are a strict grid. This means that the ball and paddles do not move smoothly; it’s quite choppy. Which is fine, but even an analog-style console like the Odyssey 100 could smoothly move the ball, so it’s a downgrade.

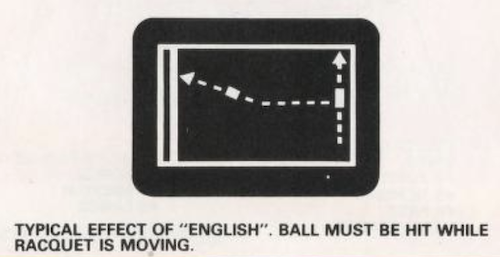

The one way that TV Arcade III puts its own spin on the Pong formula (pun intended) is with its own take on “English”. On Atari consoles, this utilized a segmented paddle to hit the ball at different angles. On the Magnavox Odyssey-like consoles, there was an extra knob to control the ball after you hit it. And here, the ball will curve after you bounce it, if you hit it while the paddle is moving. The curve is almost identical to the style seen in Bowling above and isn’t very realistic, but it does add a unique element without needing extra controls.

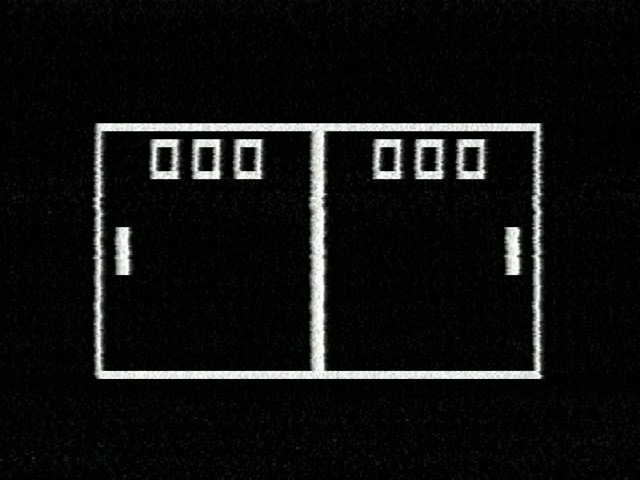

Game 2: Hockey

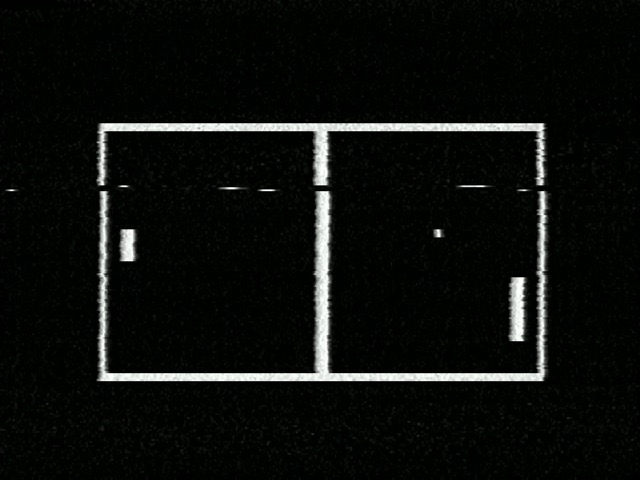

Hockey on the TV Arcade III is not like “Hockey/Soccer” on most Pong consoles; instead, this is just the default two-player Pong-like game, usually called Tennis. And it features all the same characteristics as Squash above: digital controls, a strict pixel grid, and “English”.

The strange startup dance on Squash makes a little more sense when you look at the version on Hockey.

- Turn on the Studio II with the cartridge inserted and press “CLEAR”.

- Press button “2” on keypad “A” to select Hockey.

- Each player selects their racquet size on their respective keypad, using 4 for small, 5 for medium, and 6 for large.

- Select the ball speed on keypad “A”, using 7 for slow, 8 for medium, and 9 for fast.

The reason you used keypad “B” for racquet size and keypad “A” for speed is that in Hockey, each player can choose their racquet size independently. This wasn’t a common feature in Pong consoles, but Nintendo’s Color TV Game consoles did have it.

What’s the RCA with you?

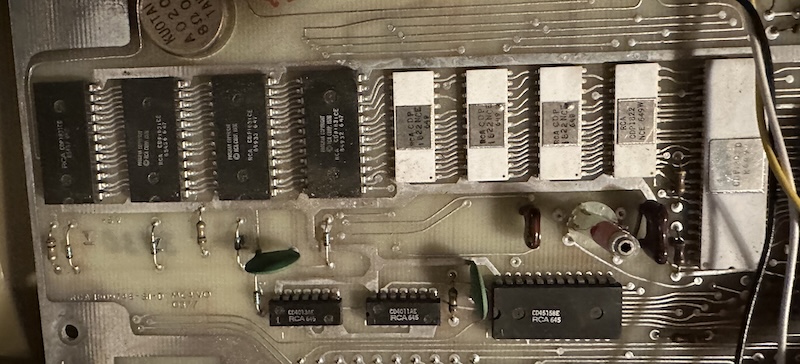

In my initial blog post, I described the RCA Studio II hardware as more interesting than the software. And I think I stand by that. This really is the interesting part:

That being said, I wouldn’t mind trying some more RCA Studio II games. (maybe Joyce Weisbecker’s game Speedway/Tag) Maybe eventually I will try to unlock the Pixie’s full-height graphics mode, even. But one thing’s for sure: I really need to do a video mod on this thing.

Thanks again to partlyhuman for the console!

A series on: The RCA Studio II

The radio company tries its hand at game consoles. Late to the market and with only monochrome graphics, how can I make this sound interesting?

- A System For The Sixties: The RCA Studio II — Historical background on the CDP1802 chipset that powers the console, and a failed attempt to get one running.

- The RCA Studio II in Living Monochrome — An actual working machine, and a look at the built-in games and a cartridge too. (Possibly a Pong console post)

- A System For The Sixties-and-a-Half: The Toshiba Visicom COM-100 — From Japan with color: Toshiba takes a spin at beefing up the Studio II for the Japanese market

- The RCA Studio II Lives On: A Package from Belgium — A gift from a modern Studio II enthusiast shows off what the system is really capable of.