Toaplan v2 and the Birth of Raizing: Sorcer Striker!

Toaplan. A company known for two things: great arcade shoot ‘em ups like Truxton, and a highly questionable translation of one of those games on the Sega Genesis. But we’ll leave all your bases aside today. The “Toaplan v1” chipset I talked about in the Truxton article of course showed its age over time, and was replaced with a new one. And Toaplan didn’t just use it themselves; they licensed that chipset to a new company entering the shoot ‘em up game. Let’s dig into Sorcer Striker, Raizing’s first title.

Sorcer What-er?

In Japan, its nation of origin, Sorcer Striker is called Mahou Daisakusen, or “Magic Grand Strategy”. It was supposed to be Mahou Daisensou, “Magic Great War”, but then Irem released Kaitei Daisensou (In the Hunt for us Anglophones), so they tweaked it to not be as similar. What matters, though, is that this was the first game for a company called Raizing. Or Eighting.

Raizing has its roots in another company, Compile. Compile was a legendary developer for console games, and in the 1980s that definitely included shoot ‘em ups, most notably the Aleste series, but also Zanac, Gun-Nac, Blazing Lazers, etc. Raizing was formed by developers who had worked on MUSHA Aleste (or just MUSHA for those of us here), and wanted to make arcade shoot’em ups. Compile, meanwhile, reoriented around games like a little obscure title called Puyo Puyo.

Compile had, at the time of the schism, only developed for consoles. So when Raizing was formed to target arcade markets, they needed to get their hands on hardware; and arcade hardware in the 1990’s was not a trivial task. Thankfully, there was another company Raizing had a connection to: Toaplan. In 1993, they were still an arcade giant, and their “v2” chipset (a modern name from reverse engineers) had been serving up hits like Truxton 2.

It’s worth noting the timelines here: Raizing is often included among the companies that were formed after Toaplan’s dissolution, like CAVE. But Raizing coexisted with Toaplan; Sorcer Striker came out just two months after V-Five (Grind Stormer), and substantially before Toaplan’s last shoot ‘em up title, the (utterly amazing) Batsugun. So at least in this period, Toaplan still exists.

Once more, in Korea

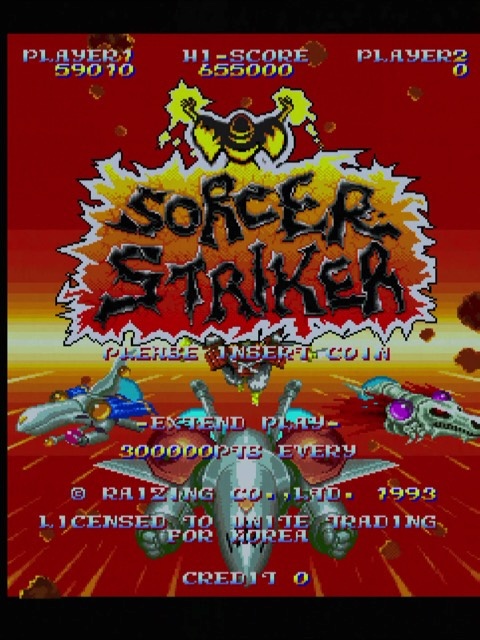

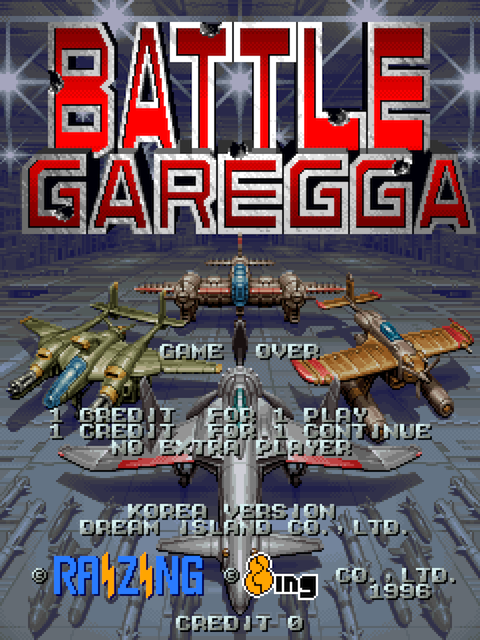

Now, if you turn on my copy of Sorcer Striker, you get this:

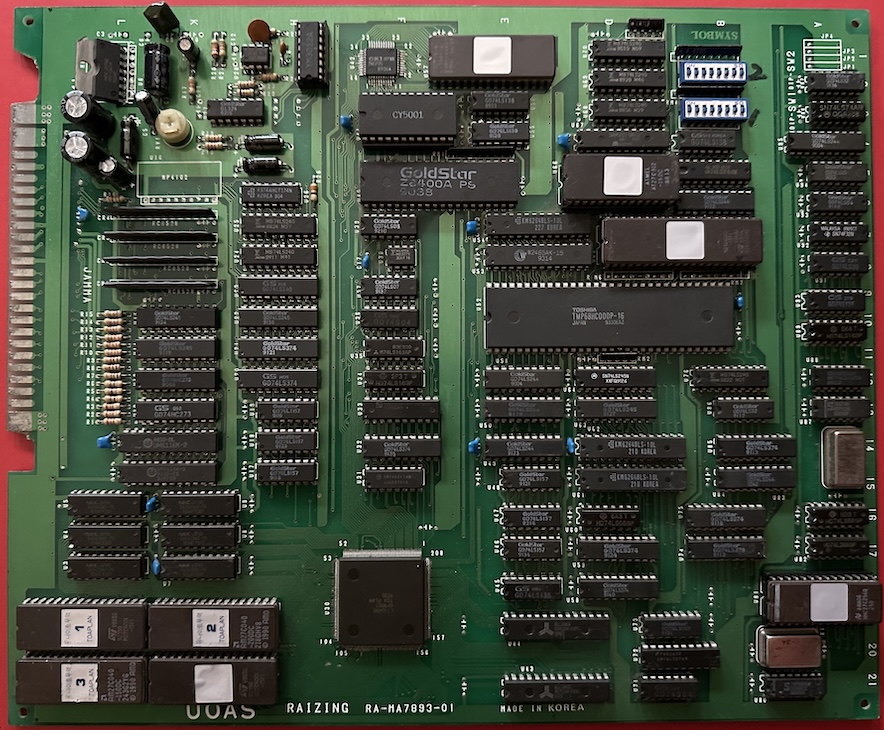

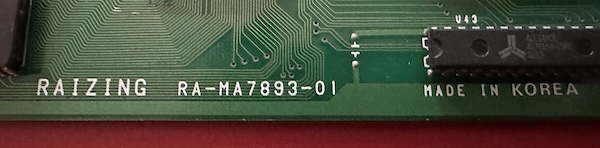

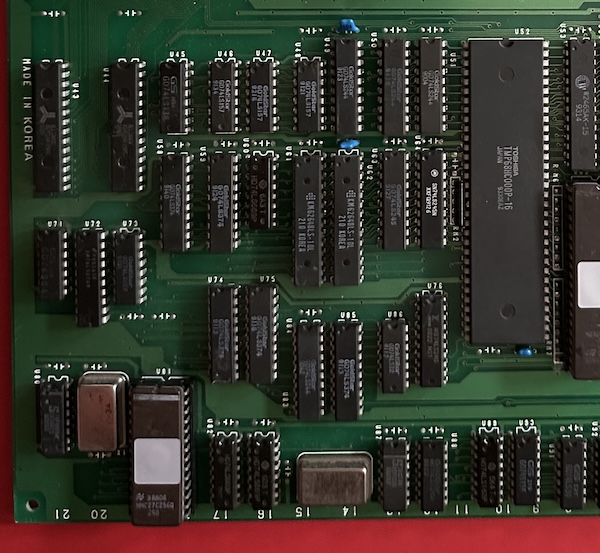

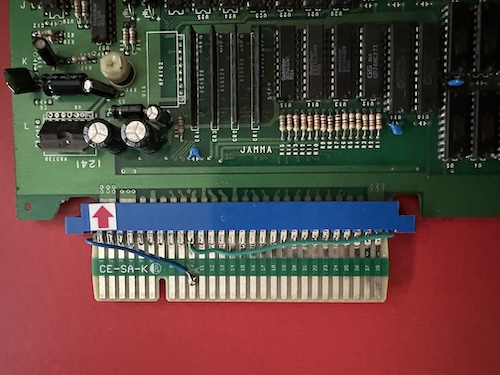

And this isn’t a fluke. Here’s the full PCB:

Notice anything? And not just the fact that the EPROM stickers in the corner say “Toaplan”. UPDATE: I’ve been informed by multiple sources that the Hangul just says “Unite Trading”.

Nope, it’s slightly to the side of that. This board isn’t just a Korean localization of Sorcer Striker, it was made in Korea.

Now, as far as I can tell, this is an entirely licensed PCB, and is, other than the place of manufacture, identical to its Japanese-made counterpart. We’re past the age of Korean copyright-free bootlegs.

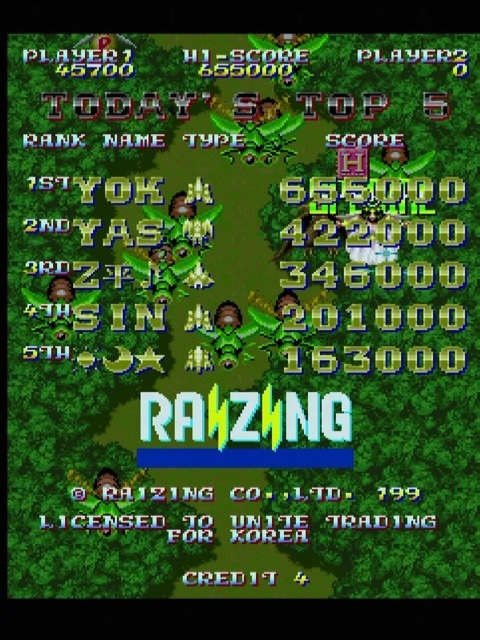

As for why the sticker says Toaplan, I do have a theory that the Unite Trading deal was something that Raizing gained through their relationship with Toaplan. After all, Unite Trading had done Korean releases for most of the later Toaplan titles, whereas later Raizing title Battle Garegga, which post-dates the collapse of Toaplan, was done through Dream Island.

But that’s just a theory.

Another fun difference for the Korean version is that while the western release is easier than the Japanese release, the Korean version actually has an even more aggressive difficulty curve. Shmups Wiki has all the details.

Hardware

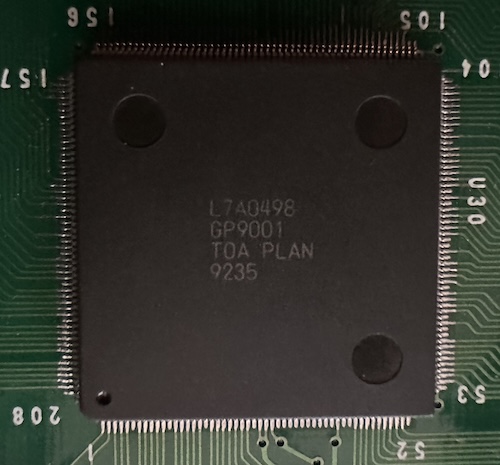

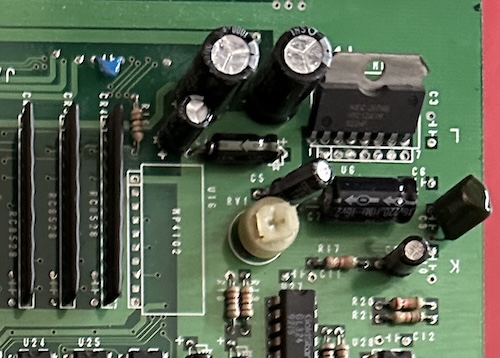

On the Truxton article, I was able to identify different parts of the board that were responsible for the tilemap and sprites. But it’s the 1990’s, the era of mass integration of circuits. Behold: three tilemaps and 256 sprites:

When I talked about the Konami Contra hardware, I noted it was often grouped based off of the presence of the 007121 tilemap and sprite processor. Similiarly, the GP9001 is the chip that makes the “Toaplan v2” hardware what it is.

Some games like Dogyuun and Batsgun used two GP9001s (doubling the sprite and tile layer capability), but later games like Grind Stormer and everything by Raizing use just one. However, most later Toaplan v2 games added a new text layer, including the Sorcer Striker board. And where is that text layer?

Um, well, the EPROM at U81 is the text layer graphics. So my assumption is that some of the discrete logic in this region is implementing the text layer? But I’m honestly not sure, and didn’t feel like tracing it out.

The benefit of a text layer to a shooter should be obvious. (The GP9001 tilemaps use 16x16 tiles) The Toaplan text layer is quite sophisticated as well, with line-level scrolling. Remember in tate games like almost everything that used this hardware, lines are vertical, not horizontal.

Hear me roar

So, let’s talk about the audio circuit. Well, first off, let’s talk about the fact that when I plugged this PCB into my supergun and turned it on, I got no audio at all. But why?

It turned out to be pretty simple. See, this is a JAMMA board, and JAMMA boards output audio that is designed to be hooked up directly to a speaker, and so have a full amplifier. Meanwhile, superguns are decided to output audio at line level, so they can feed regular consumer-style hardware like a Micomsoft Framemeister without blowing it out.

My supergun I use for posts like this is an Axunworks Supergun Mini, (yep, still!) which has a fairly nice circuit for handling this, making sure to drop the audio level. It’s pretty wasteful to amplify the audio and then drop it down, but hey, who cares.

But it has a problem. The JAMMA standard sets one pin for positive audio, and one for negative, and the circuit on the supergun takes this into account. But in reality, a bare speaker won’t care; you can reverse the positive and negative and will it work. But the supergun does care.

Thankfully, I’ve encountered this issue before, on my Asura Buster PCB; I’m just going into a bit more detail here because while I’ve seen Asura Buster listed as a game that has audio problems like this, I hadn’t seen Sorcer Striker noted. I’m not sure if this applies to the “MADE IN JAPAN” PCB or if this parity reversal is a Korean exclusive.

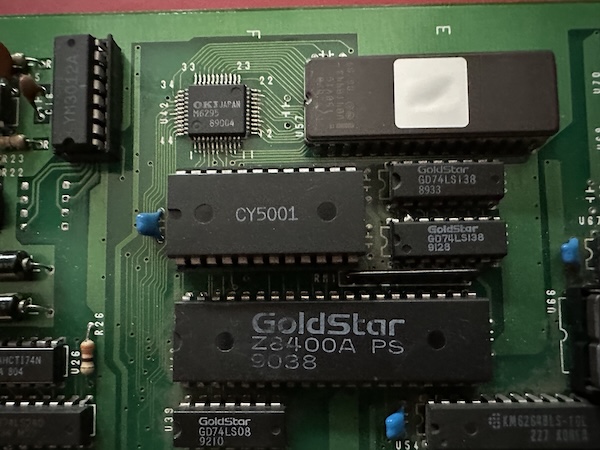

The audio section of the PCB, meanwhile, is fairly typical for an arcade board of this era. The CPU is a Goldstar Z8400A, a late second-source Z80 CPU; GoldStar provided almost all the chips on this board– in case you’re curious, today, GoldStar is the “G” of LG. (Thanks to evv42 for a minor correction here)

The “CY5001”-labeled chip is a YM2151 “OPM”, which was also used in Konami’s Contra, in Gate of Doom, and in so many other games. It’s a four-operator eight-channel FM synthesizer, and it requires the YM3012A chip to convert its digital output into analog audio output. An OKI M6295 chip, which has four ADPCM channels, is brought in for sound effects and other things FM synthesis isn’t as good at.

Audio circuits varied quite a bit on “Truxton v2” boards. For example, Grind Stormer only had a YM2151; it’s noted for its all-FM soundtrack. The YM2151-OKIM62195 pairing, on the other hand, was what Raizing went with for all of its games on this platform, and also was used by Toaplan on its last shoot ‘em up, Batsugun.

The game

So I don’t actually want to say that much about Sorcer Striker from a game design perspective. Because I’m less familiar with the Compile side of things, so I can’t really talk about what this builds on and what it isn’t.

Certainly, Sorcer Striker is a big divergence from MUSHA. Unlike that gamqe, you start by choosing one of several characters, and it follows the “main weapon and bomb” formula, similar to Truxton.

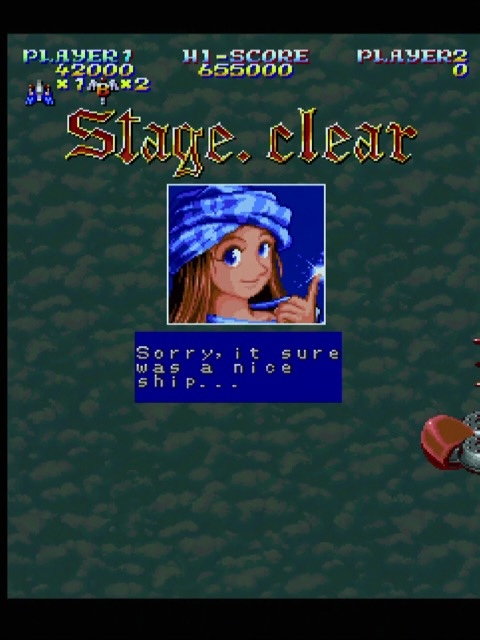

What I will say is this game has a ton of personality. Here I chose the apprentice magician Chitta as my character; not only does she have a personal quote to start the game, look in the corner to see her little sprite jumping into her ship. Spoiler: she misses. It’s adorable.

The game’s setting is fun, with a high fantasy theme where technology is magic. Here I fly over the ocean to a flying castle town, and you can even see people making the questionable decision to wave rather than go inside. As you fly over the inhabited areas, you can even shoot down gobligans who are attacking innocent civilians.

That being said, the game gets hard fast; as noted, the Korean version ramps up the difficulty, though here on stage 2 the rank is still in line with the Japanese (still much higher than the western release, though).

At least you get snarky fighting-game style quotes when you end a level. (Yep, fighting game end quotes were already a thing at this point; Street Fighter II was 1991, after all)

Keep going

The Toaplan v2 hardware remained in use by Raizing as late as 1999’s Battle Bakraid; it was just a year later in 2000 that they’d release their last two shoot ‘em ups, Great Mahou Daisakusen and 1944: The Loop Master, both on Capcom’s CPS2 hardware. With Toaplan’s bankruptcy in 1994, that’s a 5-year survival after the originator’s bankruptcy, beating out the Neo Geo, whose last game came two years after the bankruptcy of the original SNK.

The Mahou Daisakusen series got two sequels; Kingdom Grandprix (Shippu Mahou Daisakusen), a shooter game with questionable racing elements, and the aforementioned Great Mahou Daisakusen. The characters also made their appearance in other Raizing shoot ‘em ups as hidden characters; Miyamoto, the dragon, in particular seems very popular among Battle Garegga players for his speed. Definitely a cool bit of gaming lore here, backed by some excellent games and some surprisingly enduring hardware.