The Last Preset Machine: Yamaha's MR10

Earlier on the blog, I took a look at an early preset drum machine, the Panasonic RD-9844. How early was it? Not a single IC in sights, a pure discrete logic machine packed tightly into a case. Let’s take a look at the opposite end of things. The 1982 Yamaha MR10 drum machine. PLUS: Disco fever!

1982?!

1982 is extremely late for a preset-only drum machine. Roland’s CompuRhythm CR-78 came out in 1978, and the programmable TR-808 was on the market by now among many others. Indeed, even analog drum machines in general were on the way out at this point; the market was much more excited about sampled drum machines, as 1982 also brought in the LinnDrum, a cheaper successor of the Linn LM-1 that got used all over the place.

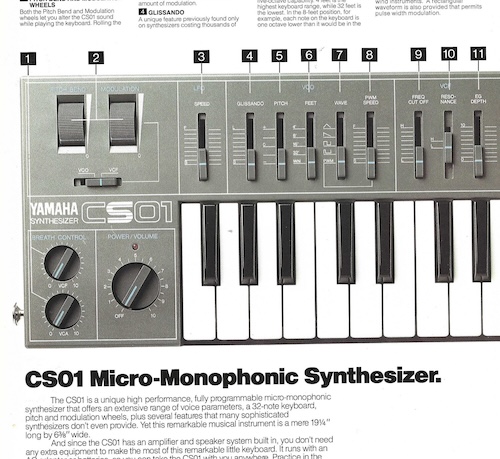

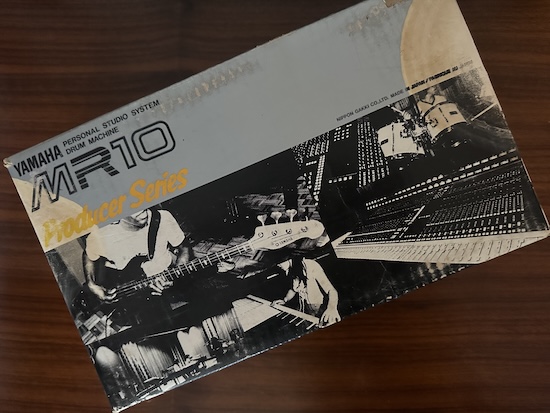

Of course, the Yamaha MR-10 wasn’t competing with the Linn samplers or the TR-808. Yamaha had a much more low-end market in mind with this, which they called the “producer series”. These were low-end portable machines, designed for live performances. Probably the most famous member of the producer series is the CS01 monophonic synthesizer. This blog post isn’t about that.

Other members of the producer series were more prosaic but practical for the performer, like the MA10 Headphone Amplifier and the MM10 mixer. Interestingly, the brochure linked on synthforbreakfast.nl doesn’t actually have the MR10.

The Yamaha MR10 also continues this focus on performance. Sure, I commented on the little preset box at the top. But notice that just as much space is taken up by five large buttons that play each of the instruments. These are designed for fingers, not drumsticks!

- Bass Drum

- Snare Drum

- High Tom

- Low Tom

- Cymbal

And take a look at the side. These are all the jacks you get, all other three sides are bare: a power supply (though it can also take batteries), the audio output (only a mixed output available!), and an input for a bass drum pedal. For actual drummers, bass drums are often controlled by a kick pedal, but it’s a little surprising to see this here.

Overall the MR10 appears to be a bit of an afterthought of the line. The image above is frequently seen in producer series marketing, including in the Yamaha MR10 manual, but you might look closer and see that nobody is using the MR10 in it! Instead, the singer and the guitarist are using amplifiers from the line, and of course the CS01 is there.

It makes sense; the MR10 simply can not really be played portably or while standing. There’s nowhere to add a strap, and given that they expected people to play complex tones on the buttons, you’d really want both hands free.

What does it sound like?

A giveaway of a late-generation preset box like this is that it has a “disco” preset; in the late 1960’s when these started out, disco was just emerging, and the target audience of preset rhythm boxes, home organists, didn’t play it. As disco grew in popularity, and as rhythm boxes started to get more use elsewhere, the need for a disco preset appeared.

I didn’t say the disco preset was very exciting, of course. Especially with the tempo knob in its middle position, it’s really pretty slow. But it exists, and that says something. You can also hear the variation here; I set the machine to “4 bar” variation.

Now, there are more knobs. The “BD VOLUME” and “CY VOLUME” do exactly what they say, controlling the volume of the bass drum and cymbals, respectively. The “TUNE” knob is more interesting. It does control the tune, but only for the high and low toms. Here’s me playing with the tune knob while the “Rhumba” preset plays.

Oddly, while the manual does list all the patterns of the drum machine, the terms for the instruments are different. According to the manual, we should have a Hi-hat, Snare Drum, Bass Drum, Cymbal, Conga, Cow Bells, and Guiro. Instead, these seven seem to be matched to the closest equivalent of the MR10’s five.

Overall, I’d say the sound of the Yamaha MR10 is very primitive; it actually quite reminds me of the Panasonic, though the sounds are a bit more shaped; in both cases, they are unapologetically analog. The difference here is that for Yamaha in 1982, they were doing this on purpose, not just to reach a price point.

You don’t make a machine like this in 1982 by accident. Yamaha did this because this was a sound, they thought, people wanted; not just because it was the cheapest way to get an approximation of a real rhythm section.

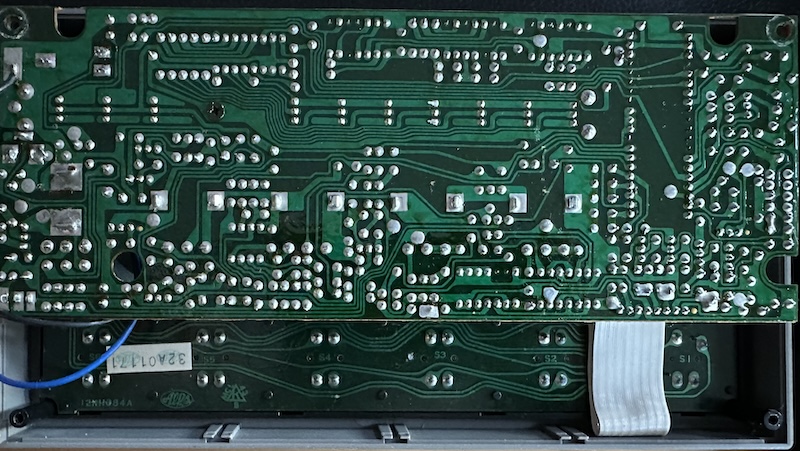

What’s inside

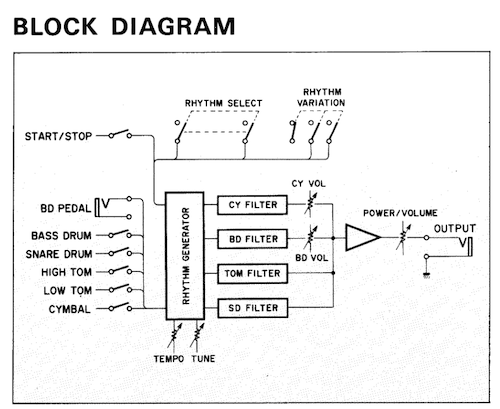

The manual for the MR10 is at the twilight of an era. On the one hand, you have a block diagram, which is more than can be said for the modern era. On the other hand, it’s extremely simple.

Everything goes into one big box, and then sounds come out, which are then mixed into the single output. The tuning and tempo potentiometers are down as the bottom, and you can also see the separate inputs for the bass pedal and the bass pad; as noted, they can be used separately. The manual is very clear to state that these can be used simultaneously.

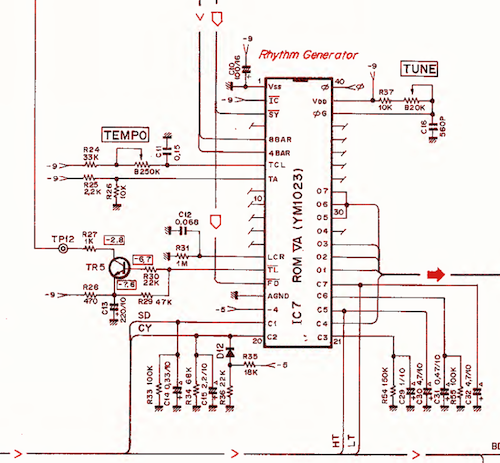

So are they just oversimplifying? Not really; take a look at the service manual on the Internet Archive. Everything flows into IC7, the YM1023. The service manual calls it a ROM, but it’s clearly not just your normal ROM, when the tuning and tempo analog values go right in.

That being said, there is definitely ROM in that chip. At this point in time, diode matricies had disappeared even for preset machines. Yamaha, in their typical fashion, just went even more integrated. Unfortunately, this means we can’t decompose the circuits for each sound like I did the Panasonic; the discrete circuits here are just basic filters, the real work happens inside the chip. This also makes this less desirable for modding or circuit bending.

The MR10 is easy enough to open, with just four screws. I did need a 9/16 socket to remove the nut on the bass pedal jack. That was as far as I got, though; thanks to the soft plastic that’s shrunk over time, I couldn’t figure out a way to remove the knobs that wouldn’t damage them in the process. If I needed to repair this I’d take the risk, but as it stands I’m just looking for curiosity.

You can see the large DIP chip on the side, which is likely our ROM. I notice not all the pins are connected; have to wonder if some are debug, or if they’re really all just unused. I guess we’d need a die shot to know for sure.

Simple, and that’s the point

The Yamaha MR10 is weird. It’s clearly a throwback even in its time; but it’s not a throwback to Yamaha; the only analog rhythm machines they had made before this were built into Electone organs. In a sense, then, this is a goodbye to the analog rhythm section, as Yamaha too moved to digital samples. (Like, for example, those built into the OPL series) It’s also clearly designed for the lowest of the low-end market, a companion to the home musician who just wants something to keep the beat. Compare to the Panasonic from a decade earlier in the same niche, it’s quite a bit nicer.

But while it was cheap, not having programmable rhythms is a real strong limitation compared to contemporary analog boxes like the Roland TR-606 for the modern retro music enthusiast. I guess today these are mostly used to sample; at that point, you don’t care about the internal sequencer or lack thereof, and it does have an unapologetically analog sound. And it definitely gets to keep its spot on the corner of my Hammond; none of my other preset machines have disco!