What did we do to deserve the PC-FX? (and the PC-FX GA)

I’ve enjoyed digging into the curiosities surrounding NEC and Hudson Soft’s PC Engine consoles, from the LaserActive to the SuperGrafx to the Arcade Card to the forbidden combination. But this is where it ends: the successor to the PC Engine. The last console from NEC. The beautiful, infamous PC-FX. Oh, and the PC-FX GA! What’s with that?

Behold the PC-FX

The Wikipedia page on the PC-FX’s history starts in 1899. I don’t think they were planning the console at that point, but you never really know I guess.

The page goes on to claim that the PC-FX started out as “Iron Man” (“Tetsujin”, in Hudson’s native Japanese), a prototype in 1992 designed to render 3d graphics over pre-rendered backgrounds. Fans of the Sega CD’s rendition of Silpheed might get excited about this.

The “Tetsujin” prototype was not released, but became the basis of the PC-FX two years later, with its 3D capability stripped out, but keeping the digital video capabilities. You might be tempted to compare the PC-FX to the LaserActive, but that’s not exactly fair. The LaserActive PAC N-1 had two shooters, the PC-FX only had one.

What’s in the box

Now, I’m a bit skeptical of the Wikipedia page here, because it also makes the claim that the custom processors were reduced from a count of five down to one. But the very pictures of the motherboard further down on that page show that isn’t true! In fact, the PC-FX as released had five custom processors:

- 2x HuC6270, the same VDC used in the PC Engine and SuperGrafx. There are two here, just like the SuperGrafx. Unlike the PC Engine, each of these has 128KB of VRAM. Internal documents seem to call these “7up”. Like the SuperGrafx, these share thirty-two palettes. (16 for sprites, 16 for the background)

- The HuC6272 “King”, which has ADPCM sound output, four more advanced background layers and handles RAM transfers. It has 1MB of RAM of its own.

- The HuC6271 “Rainbow”, which decodes motion JPEG video and puts the output into the RAM of “King”.

- The HuC6261 “New Iron Guanyin”, which combines all video output and handles palettes; you can consider it a more advanced combination of the VCE and priority controller from the SuperGrafx

- The HuC6230 “SoundBox”, provides PSG audio, and processes CD audio as well as the ADPCM from “King”.

(My main source is here )

You could also consider the V810 CPU, a 32-bit RISC design, a custom processor since it was a proprietary NEC design, but unlike the rest of the PC-FX chipset, it was used in other applications. (Most familiar to the audience of this blog is probably the Nintendo Virtual Boy) It’s possible Wikipedia may not consider the HuC6270 to be a custom processor since it was reused, but that hardly gets you down to one. It does seem that originally Hudson wanted to create their own CPU, which was what “Tetsujin” used.

This is a lot of custom hardware; it’s no wonder the PC-FX was one of the most expensive consoles of its generation.

The allure of the silver screen

What did all of this hardware get you? You’ll often see descriptions of the PC-FX as having nine scrolling background layers. But now it should be clear where these come from:

- 2 HuC6270 background layers

- 2 HuC6270 sprite layers (64 sprites each)

- 4 King background layers (can be scaled and rotated)

- 1 Motion JPEG layer from RAINBOW

This was not a simple console; and while frequently described as a 2D powerhouse, much of its 2D capability came from the same chips that powered the PC Engine and SuperGrafx! (Of course, backed by palettes from the HuC6271 and a faster 32-bit CPU) With “Tetsujin”’s 3D capability removed, there was just one standout feature: that motion JPEG decoding.

Motion JPEG is a simple video standard that encodes digital video into a series of JPEG images. (Yes, the familiar still image format) As you can guess, this isn’t the most efficient mode of compression, but video compression in the 1990s was in its infancy compared to today. The MJPEG decoding provided by Rainbow made the PC-FX the ultimate FMV console of its day, excluding perhaps the LaserActive.

And so it really should be no surprise that the PC-FX library centers heavily around games that use this FMV capability; especially anime games and dating sims. This, combined with an NEC business model that targeted young adults who had “outgrown” the PC Engine, has given it a reputation as “the hentai console”. But it’s worth noting that only a small percentage of the library was actually anything adult. Anime, meanwhile, is almost everywhere.

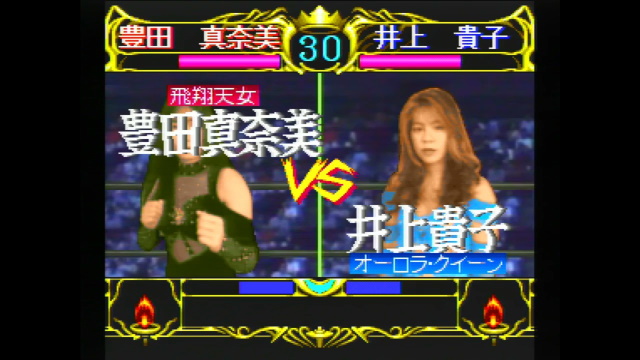

Oh, and there’s women’s pro wrestling too, if you’re too classy for anime.

The library

If you’re in the west, there are three games that get talked about for the PC-FX: the shooter Choushin Henki Zeroigar, the licensed beat-em-up’ Kishin Douji Zenki FX, and the single-screen platformer Chip-chan Ki~ck!. This is mostly because they’re the easiest to play without knowing Japanese.

Of the three, the only one I have is Chip-chan Ki~ck!. The other two get to be very expensive nowadays, and I’m not sure why this one tends to be a bit cheaper. Maybe it just sold better, or maybe it’s the aesthetic isn’t as appealing to the modern Western collector audience?

It’s actually a pretty decent Bubble Bobble-style game. And it’s one of the few PC-FX games to show off that parallax scrolling! (Though only between stages; much like Aspect Star “N”, it is a single-screen at a time game) The PC Engine can’t do that!

But yeah, let’s move on.

Let’s get freaky

Honestly, judging consoles by how they appeal to an audience over twenty years later in a different country is pretty silly, wouldn’t you say? And if we want to talk about the PC-FX’s appeal to a Japanese audience… well, the fact that it sold less than 500,000 total units implies it didn’t have much appeal there either. So who did it appeal to?

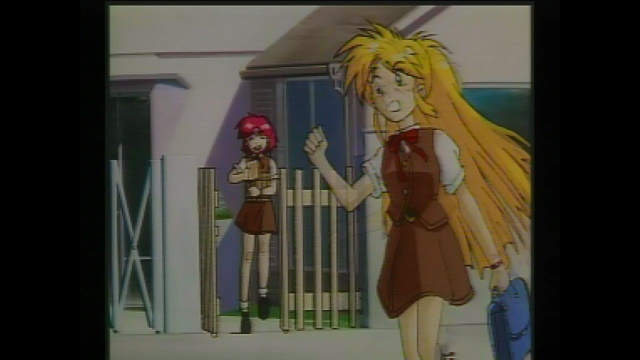

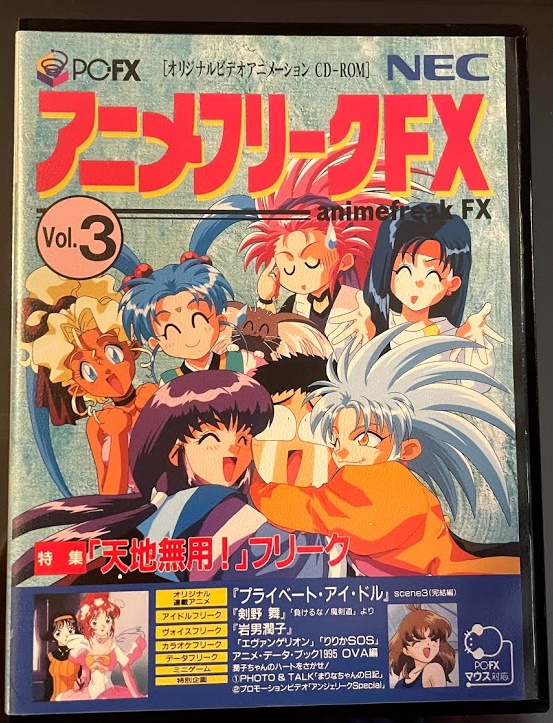

This is Anime Freak, Vol. 3. You can think of this as a magazine in the form of a PC-FX disk. There were six volumes of this in total, spanning pretty much the entire life of the console. The magazine was heavily promoted alongside the console, so you can think of this as an explanation to who the console was selling. And what those people wanted, apparently, was Tenchi Muyo! (Which did get a PC-FX game, but I don’t own it)

Anime Freak is not a game, but it’s really neat as a time capsule. You can see on the menu a Tenchi Muyo! preview, as well as an episode of anime based on the PC Engine game Private Eyedol, along with sections dedicated to idols, voice actors, and karaoke. This sort of multimedia software was pretty common in the 1990s, though it was eclipsed by the internet.

If you want a game, there is a simple mini game that’s a guessing game you play with an idol. She gives you a series of boxes to guess which one contains her heart. Unfortunately, I didn’t get it correct.

Oh, and the aqua-haired girl is Rolfee, the mascot of the PC-FX. She featured heavily in marketing, asking people to play anime games with her. You can think of her as the PC-FX’s version of Johnny Turbo, with the difference that Rolfee doesn’t leave the house. Another difference is that Rolfee eventually got her own game, Tonari no Princess Rolfee.

Believe it or not, this wasn’t that shocking of a place to take the PC Engine. While in the west we generally associate the TurboGrafx-16 with shooters and Castlevania: Rondo of Blood, in Japan anime games had become a huge part of the console following the release of the CD system. Even following the release of the Super Famicom, the combination of the CD system which Nintendo didn’t have, and a much larger color palette than the Sega Mega Drive gave the PC Engine platform a clear advantage. The only thing missing was high-quality FMV.

Still, a Hudson Soft console without a Bomberman game? Or even Bonk? The PC-FX was facing an uphill battle; being more expensive than the competition and its dedication to a small niche even in Japan makes its sales flop unsurprising in retrospect.

But what’s the PC-FX GA?

So, it’s time for a spoiler here: even though I showed a photo of the PC-FX console above, none of these photos were captured from that console. Oh, sure, the console works fine. But I didn’t feel like moving it from the living room setup which doesn’t have capture setup. So, instead, I just went out to the store and got one of these:

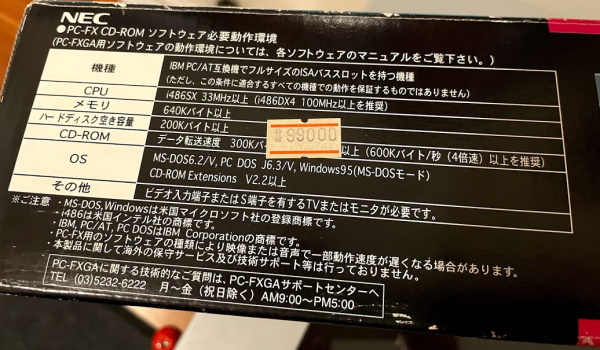

The PC-FX GA, for DOS/V. As we can see from the specs on the side of the box (which sadly have had a tag applied that I don’t want to risk removing), this is a 16-bit ISA expansion card for PCs running MS-DOS; specifically, MS-DOS6.2/V, with a 486 or better CPU and a CD-ROM drive.

So what was the “/V” in MS-DOS/V? After all, this is a standard ISA card; unlike the other variant of the PC-FX GA, it runs on standard IBM PC-compatibles that you could’ve bought in the west? For that, we need to digress.

A digression on graphics

This is ZZT, an MS-DOS game from 1990, running in VGA text mode. In the 1980’s and early 1990s, text mode was a big deal; the famous MS-DOS prompt ran in it, as did many pieces of business software. While the GUI was slowly gaining influence, it really took the release of Windows 95 for it to become truly mainstream in the business market.

So what is text mode? Essentially your video card has a set of 256 hard-coded characters, and can display only those in an 80x25 grid. (Sometimes software can redefine the font) 256 characters works very well for English, which has 26 Latin characters; even with upper and lower case and punctuation, that fits comfortably within the 256 characters. Most other languages that use alphabetical scripts also fit well in that limit, even if they also use accented characters.

Because of this, the IBM PC and its clones included additional drawing characters in the unused characters; this is what made ZZT possible, for example. However, when we look at the Japanese language, this simply isn’t possible: Japanese has two syllabaries (kana), katakana and hiragana, each comprising 46 characters. But it also uses Chinese logographic characters (kanji), of which the bare minimum would be the 2,000 jouyou kanji taught in elementary schools. (Some early Japanese computers and video games only used kana, but this would be unacceptable in, say, a word processor)

The Japanese PC-98 standard, also by NEC, supported kanji by using the two-byte Shift-JIS standard in its text mode. But this was a proprietary standard; unlike the PC market, NEC maintained strict control over PC-98 production. DOS/V was Microsoft’s attempt to bring Japanese support to MS-DOS using “standard” PC hardware. And it did it by moving MS-DOS from text mode to graphics mode, using VGA. That’s DOS/V: DOS for VGA.

Don’t worry about what the text says, we’ll discuss that later. The important thing to note is that this is running on the same computer as the screenshot of ZZT above. You can see that it’s not using the font from the BIOS, and that this screenshot has all of hiragana, katakana, and multiple kanji.

You can also see something interesting; the screen is narrower than the screenshot. That’s an artifact of my capture setup: VGA text mode is 720 pixels wide, but graphics mode is 640 pixels wide. On a CRT, of course, in both cases they’d just take the full width of your screen.

Digression over

So, now that we know that DOS/V just uses standard PC hardware, we need a standard PC to put that hardware in. And do I have just the PC!

This is a bog-standard PC tower, quite dirty, but other than that no worse for wear. It was put together by PFL Systems, which as far as I can tell was a tiny local PC builder on the South Shore of Massachusetts; this is in fact the very computer that I used as a child. Indeed, it’s the very computer on which I learned what the PC-FX was! Being from 1997, it just barely overlaps the lifespan of the console, which was discontinued in 1998. And what are the specs?

| “The Old Computer” | PC-FX | |

|---|---|---|

| Year released | 1997 | 1994 |

| CPU | 200 MHz Intel Pentium w/ MMX | 21.5 MHz NEC V810 RISC |

| RAM | 32 MB | 2 MB RAM, 1.25 MB VRAM |

| Graphics Resolution | SVGA 1024x768 | 640x448 |

| Storage | 3.5GB HDD | 32KB Backup RAM |

| CD-ROM | 24X | 2X |

Technology moved fast in the 90’s. (I should also note that for this purpose, I’ve replaced the 3.5GB HDD with a 2GB CompactFlash card with a copy of Japanese-language Windows 95) But most importantly for our purposes, this old computer used both PCI and 16-bit ISA slots. And it has a huge full-sized metal case; you can see why that’s a requirement by taking a look at the PC-FX GA card.

This is a full-width card. Indeed, it only fit in the bottom slot of this computer, due to things in the way on the motherboard. But it fit! And thankfully I don’t need that long slot for a CGA card. This card is very easy to install; it doesn’t need to connect to any other cards internally or even the CD-ROM drive. Here’s an installation guide, though, in case you like to configure dip switches or something.

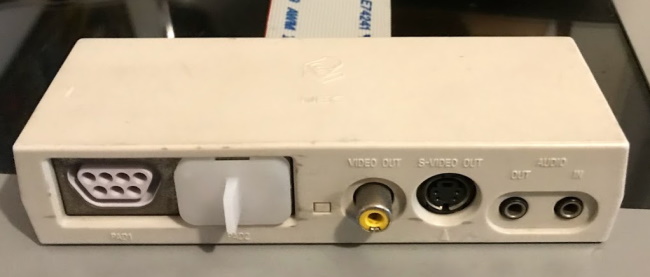

The PC-FX GA was originally released for the PC-98; I don’t have one, but it seems that the PC-98 had thicker brackets. The brackets of a PC ISA card are too narrow to fit the wide PC-FX gamepad ports (ironically, the mini-DIN ports used by the PC Engine would’ve worked just fine), so they created instead a ribbon cable that connects to an external box.

So the first surprising thing about the card is that even though it was designed for DOS/V, which has VGA output, it doesn’t actually output over the VGA card, or even do a video passthrough. Instead, it has its own S-Video and composite output, just like the PC-FX console. (The PC-FX uses a YUV colorspace for its palettes, so RGB output simply isn’t going to happen without some translation circuitry)

Audio is output over a 3.5mm jack rather than RCA jacks, likely just for space concerns. The audio in is necessary because the PC-FX can’t get the sound from your CD-ROM drive; in fact, since it’s only used for CD audio, if your CD-ROM drive has a headphone out like mine does, you can just use that.

Play the game

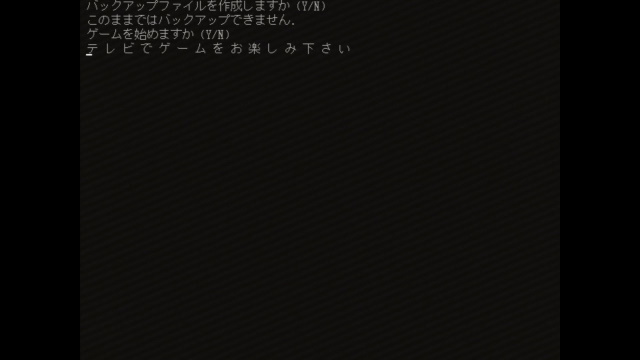

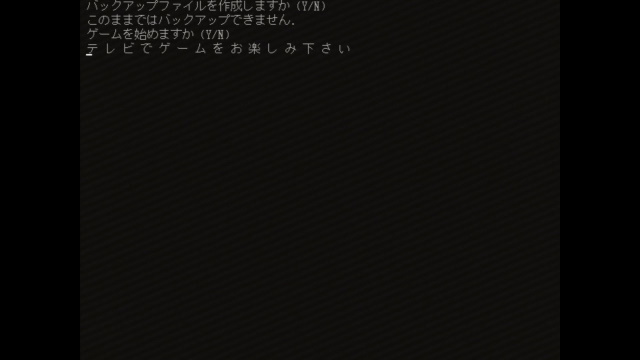

Playing PC-FX games on the PC-FX GA is pretty simple. Install the software (which really just creates a batch file with the correct IO port) and run it, and then you get a screen like this:

The text translates as follows, noting that I didn’t have backup RAM set up at the time of this screenshot (more on that later).

Continue without Backup RAM? (Y/N)

Henceforth, backup RAM will not be available.

Continue loading game? (Y/N)

Please enjoy playing the game on your television!

And that’s all you’ll see from the VGA output. Switch over to the S-Video, though, and you’ll get the familiar PC-FX BIOS screen. Well, mostly familiar. Unlike the PC-FX BIOS, you can’t play audio CDs. I guess they figured you already had that capability on your normal computer OS. The text just says “This is not a PC-FX CD-ROM”.

So, once you start the game, is there any difference for the PC-FX GA? Well, yes and no. As far as I know, no games do anything different for the PC-FX GA. But, you’ll notice a dramatic improvement, at least you will for the setup I have: the extra speed of the CD-ROM drive! Since it’s just using the PC’s CD-ROM driver, it’s getting the benefit of the higher speeds. The PC-FX loads a lot of data from disc at a time, so that’s definitely noticeable and makes the console a lot more bearable to play.

Backup RAM

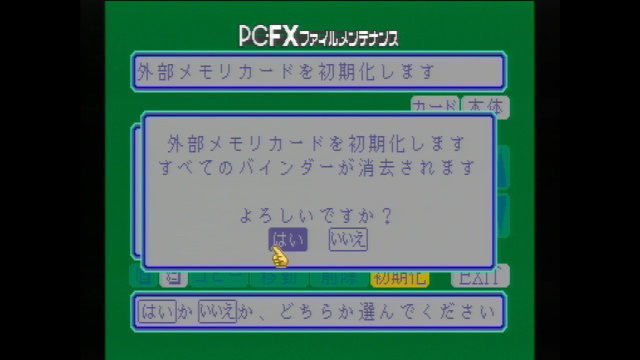

So you’ve got your PC-FX GA set up, and you break out your copy of Galaxy Fraulein Yuna FX only to be met with the following message:

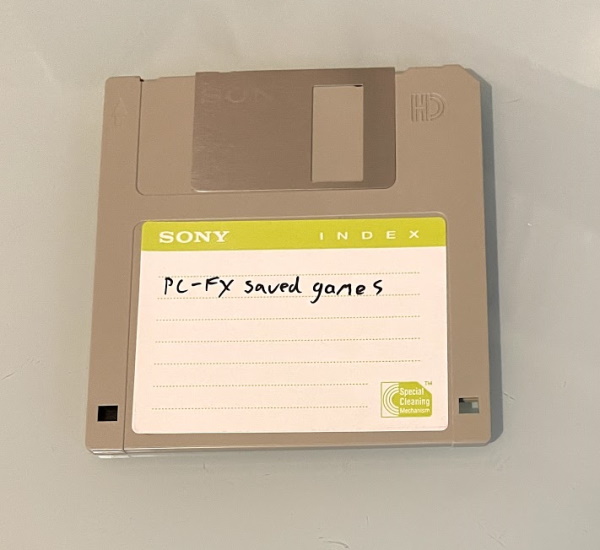

You see, Yuna FX requires backup RAM to even let you play the game. I mentioned that the PC-FX has 32KB of onboard backup RAM about; it can also be augmented with a 128KB FX-BMP memory card. But that RAM doesn’t exist on the PC-FX GA ISA card. So how do you save your game? With one of these bad boys!

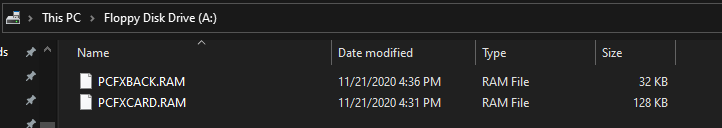

Well, by default anyway. You can adjust the configuration files to save to the hard disk, but it defaults to using the A:\ drive as a location to store backups. And what does it store?

The PC-FX GA just emulates the storage options I mentioned above; PCFXBACK.RAM is the 32 KB of internal backup memory, PCFXCARD.RAM would be the external memory card. And just creating those files isn’t enough to make Galaxy Fraulein Yuna happy; you also need to format the files, just like if your backup RAM was replaced. For that, you have to use the system BIOS.

Once you’ve saved games on the memory card, the files become populated just like they were RAM. I wonder if it’s possible to take save games from emulators and inject them into the file here or vice-versa; unfortunately, I don’t think there’s any way to move a saved game into the GA from the standard PC-FX.

But wait, there’s more!

So if the PC-FX GA was just a way to play PC-FX games using your PC’s CD-ROM drive, it really wouldn’t be that interesting. However, the PC-FX GA has one chip that the PC-FX doesn’t. Let’s zoom in.

This chip stood out, the HuC6273, because it’s not on the standard PC-FX, and it has a second logo, “Kubota”. Who are Kubota? They are a Japanese tractor and agriculture company. Will the HuC6273 till my fields? No; in the 1990s Kubota had branched out into workstations and 3d graphics, acquiring assets from Newton, MA-based Stardent. Their graphics arm was bought by AccelGraphics in 1994, which was in turn acquired by Evans and Sutherland in 1998. This is a 3D graphics chip, most likely the one that was left off of the Tetsujin.

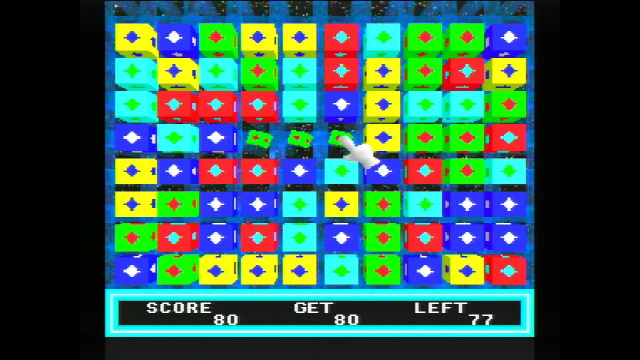

The PC-FX GA came with a game Same Game FX. You can’t play this game on your PC-FX; trust me, I tried, and just got nothing. But on the PC-FX GA, you get…

It’s mostly a glorified tech demo. But this is indeed something that would be much harder to do on a stock PC-FX! (It may be possible by pre-rendering everything, but only because the game is so simple)

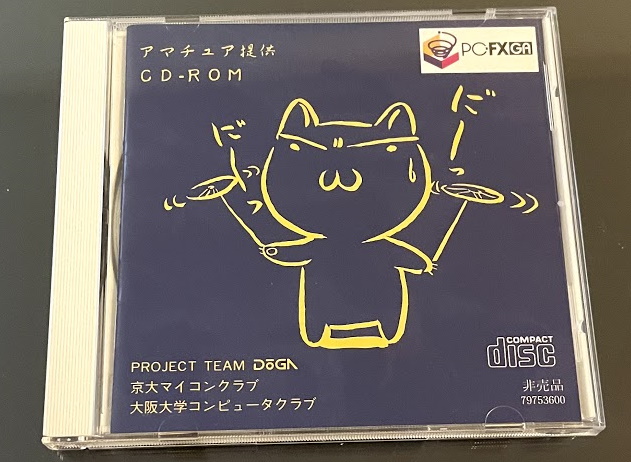

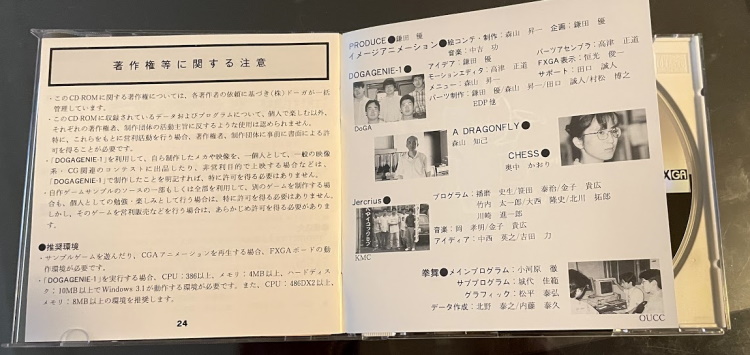

The second disk, Amateur Teikyou, is more interesting. This is, as the name implies, a group of amateur programs for the PC-FX GA. The programmers even got their photos included in the booklet.

And this CD-ROM is not a PC-FX game; you boot it from Windows or MS-DOS, not from the PC-FX GA BIOS. The computer can take control of the PC-FX hardware and do various things with it. That Kubota chip seems to be pretty decent.

Now, you might notice that my disc is blue; this is actually the PC98 version, and as a result, doesn’t actually run on the PC-FX GA. Unfortunately, my PC-FX GA didn’t come with the CDs so I had to purchase them separately, and didn’t realize at the time that Amateur Teikyou was system-specific. (The PC98 PC-FX GA seems to be more common.) If you want to dig into this collection more, I recommend YouTuber Lazy Game Review’s video. He also uploaded the dinosaur demo.

That’s it?

So, that’s the PC-FX, the last attempt by NEC to create a successor to the PC Engine. And the PC-FX GA DOS/V edition, the less popular variant of a variant of the console. There’s not much further to go with NEC here; in 1998 they left the game console business. In 1999, the last licensed game for an NEC console, Dead of the Brain Vol. 1 & 2, was released for the PC Engine Super CD-ROM2. Hudson Soft seems to have left the hardware business, and was acquired by Konami in 2011 and eventually dissolved into it.

There’s a little bit more to see on the PC-FX GA, though. The PC-FX GA was designed to be used not only as a way to play games and look at other’s demos, but to make demos and even games oneself. I’ve acquired a piece of software called “GMAKER”; unfortunately, at the moment I’ve not been able to run it, possibly because I’m on Windows 95 and GMAKER seems to require Windows 3.1; if I can get that working, I suspect it’ll warrant a whole blog post of its own.

But for now, I’ll leave you with some Zork. Of course there’s Zork on the PC-FX! Well, Return to Zork. It’d be hard to play the original without a keyboard.