Adaptation and Re-adaptation: The story of Pitfall II

The video game console originated as a way to bring arcade experiences (specifically, Pong) into the home. But the home game took on a life of its own; playing a game in your house that you can play indefinitely is very different than a game that needs to constantly shuffle through new players to get the quarters of each. One early game that understood that difference was 1984’s Pitfall II. Let’s put on our amateur video game analyst hats and take a look into gaming history.

Pitfall!

Made by David Crane in 1982, Pitfall! is arguably the first video game that originated on consoles (as opposed to the arcades or computers) to be a real hit. Selling over four million copies on its original Atari 2600 and countless more on successive platforms (like the MSX, pictured above), the flip-screen game created the side-scrolling platformer, creating a large world that extended beyond the bounds of the television.

Pitfall! never made it to the arcades; it being the flagship of Activision, which never really entered that realm, and instead pioneered the concept of a third-party console publisher. Still, when we look at the game, it does have something of an arcade mindset. The game is built around a strict 20-minute timer; even if you play perfectly, your game will end when time is up. The player is further limited by a small number of lives.

Despite originating the flip-screen platformer, Pitfall!’s world is more complex than a simple left-to-right slog; not only can you move “backwards”, you can also move below, in an underground passage that allows you to rapidly move forwards, but is often blocked by walls. Thus, the game takes on a complex exploratory element, as you play it many times to build up the correct route, very much like an arcade game that you don’t have to pay quarters for.

This isn’t to imply that Pitfall! was primitive or a relic of the past. On the contrary, it stands out among Atari 2600 games that I find it easy to go back and play even today; a rarity on that console. And it’s also quite a technical feat. I’m only bringing the game up at all to contrast to the sequel.

Behold the lost caverns

Pitfall II: Lost Caverns presents a simple enough scenario. Pitfall Harry needs to collect the Raj diamond in the lost caverns underneath Macchu Picchu. Alongside that, he needs to find his niece Rhonda and his bipedal pet mountain lion, Quickclaw (both from a Saturday morning cartoon) who got lost, and also find some gold bars stolen from Fort Knox. It’s a simple enough premise, and it’s easier to excuse Harry’s theft of cultural artifacts when a diamond with a Hindi name probably didn’t actually belong to the Inca anyway.

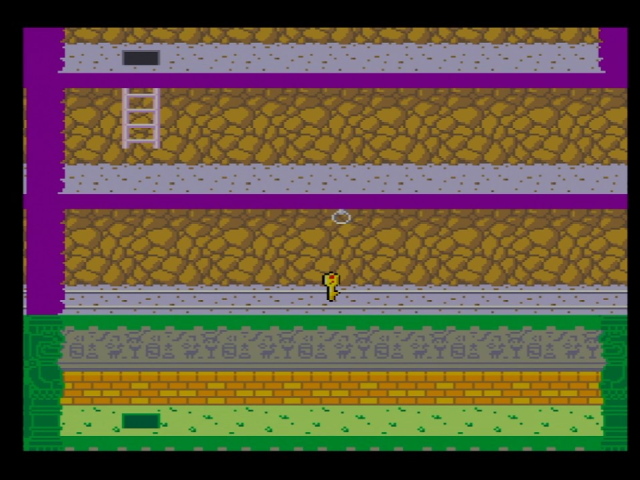

Let’s take a look at the very beginning of the game. This is the first thing a player sees. Pitfall Harry stands on a plus sign, and below him in the cave is Quickclaw. But the cave has a crucial difference– a ladder going down. And proceeding further will reveal that you can’t just go back to get him. (In fact, Quickclaw is typically the last thing a player collects) If you try to go and collect Quickclaw, you’ll also reveal something else:

The screen scrolls down. While Pitfall II is still a flip-screen platformer horizontally, it is a proper vertical scrolling platformer, each of its flip-screens extends quite a ways below. This gives the world a much more two-dimensional nature compared to Pitfall!. Remember too that this game came out in 1984, before Super Mario Bros.

The world of Pitfall II plays out as a single large interconnected level; in modern terms, you could call it an open-world game. But while the world is maze-like, the Pitfall! focus on treasure-hunting makes it feel less harsh. Dead ends are almost always rewarded with a gold bar for your troubles. The game pushes you to get a higher score, a maximum of which is 199,000; a perfect game.

One very cool element of Pitfall II for its time is the music. It features a full in-game soundtrack, even on the Atari 2600 (using an extra add-on chip called “DPC”, for either Display Processor Chip, or, perhaps, David P. Crane). That soundtrack varies as well; take this clip from the Atari computer version. (The 2600 music is the same composition but slightly lower-pitched, and a bit staticky due to the limitations of the TIA) It starts out as a triumphant opening, and then goes into a “neutral” section around nineteen seconds which repeats over and over.

When you collect a gold bar, it resets to the “triumphant” opening. And when you get hurt, it goes into a minor key, depressed version of the triumphant opening, while your character flashes and goes back to the last checkpoint while your score plummets throughout. Dying further away from the checkpoint punishes you more than dying close to it.

The checkpoint system is where Pitfall II really shines. The game feels almost like a modern “indie” platformer; there are no lives or time limit here. You can fail as much as you need and try, try again. However, there are greater rewards (in this case, higher score) and bragging rights if you can go forward without dying. This is a game that is completely at home on console, and would be completely lost in the arcade. It worked pretty well on computers, too, who were starting to have the graphics and sound chops to rival consoles.

I don’t want to say that Pitfall II is perfect. The jump physics are clearly pre-Super Mario Bros. and so don’t have the smooth performance you’d associate with that game. The balloon pictured above can be particularly frustrating if you don’t realize that you have to wait for it, as initially you just see a regular bat enemy. But still, it’s a very innovative game.

And it sold well; I see figures of 1.3 million reported for the Atari 2600 game; sure, not as well as Pitfall! did, but remember that it was released in 1984, at a point when the North American video game market was widely considered completely dead. While the 2600 would linger on for the rest of the decade selling whatever unsold stock Jack Tramiel could find under his couch cushions, Pitfall II was its last great hit.

Adaptation to computers

The rest of this blog post is about adaptation, which crosses nicely with a well-known bit of video game industry lore.

Overall, the ports of Pitfall II away from the Atari 2600, such as Robert Rutkowski’s ColecoVision and MSX ports, stayed pretty close to the original formula, keeping the same world layout and quest, and primarily only differing due to the graphical differences between different game consoles. An exception, however, was the Atari 8-bit computer ports, the “Adventurer’s Edition”, along with the very similar Atari 5200, programmed by Mike Lorenzen. (Who, as a fun aside, apparently was later involved in Accolade’s bypass of the Sega Genesis security system)

The Atari 8-bit computer architecture was designed as an upgrade of the Atari VCS, and could be coded in the same way. (Of course, it also had more programmer conveniences to avoid the need for “racing the beam”) The coders tasked with the port decided to port the game based off of David Crane’s source code directly, which allowed for extra time to include an entirely new second level. When Pitfall Harry “jumped for joy” at the end, a portal could open to bring him to an entirely new map that could be seen past the first one.

Activision’s marketing department, as reported by Activision producer Brad Fregger in his interview with Perifractic, didn’t want to have such a dramatic difference between the versions and so it became an easter egg rather than a properly-advertised feature.

Well, that’s the story

So despite the interview with Activision employees confirming it, I’m not quite sure this was really an easter egg. Let’s take a look at this quote from the Pitfall II manual.

I’m not sure how Activision worked in the 80’s, but my understanding was this sort of thing would probably have been run by marketing. You can see the second quest mentioned right there; and it’s not mentioned in the otherwise very similar manual for say, the ColecoVision version, which of course doesn’t have a second quest. This bit of internet lore may have just gotten a bit out of hand; perhaps they just didn’t want to advertise one version as superior.

Second quest or no second quest, home computers are a lot like console games, and the mechanics of checkpoints translated well. Console gamers and computer gamers, contrary to what the internet tells you, are not that different– they both buy their game once up-front and then play for hours. What happens when Harry hops on his balloon and floats over to a wholly different world: the arcade?

Pitfall II: The Game The Game

Sega went through a brief period where they licensed western computer and console games like Choplifter to create arcade variants; in 1985, Pitfall II was given the treatment. Actually, it’s not quite fair to say Pitfall II: The Lost Caverns is a port of Pitfall II: Lost Caverns; Sega’s license seems to have extended across the Pitfall franchise, such as there could be said to be one.

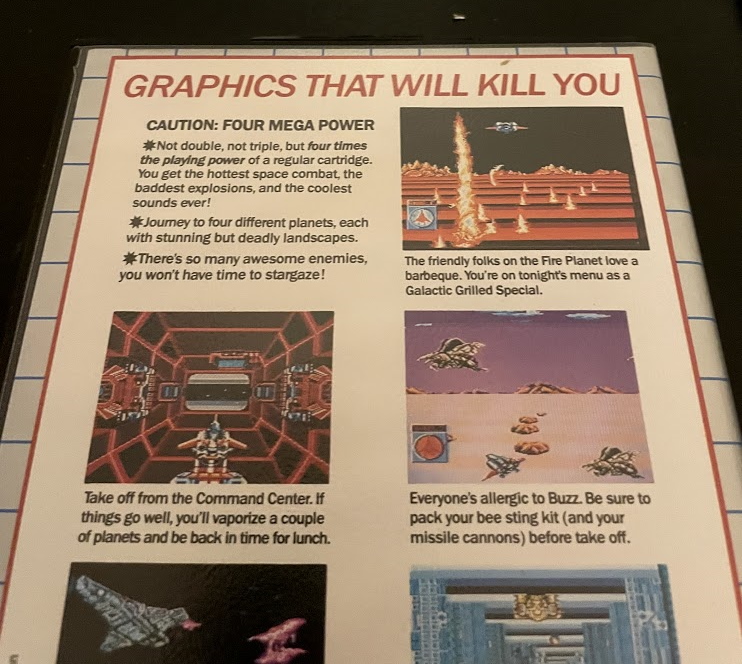

Taking a game so perfectly suited and designed for the console and computer market, and bringing it to the arcade market was a daunting task. After all, Pitfall II could be played over and over for hours until you won. An arcade machine where a single player could just keep playing would flop. So some adjustments were needed. Similarly, the graphics too needed an upgrade.

Hardware

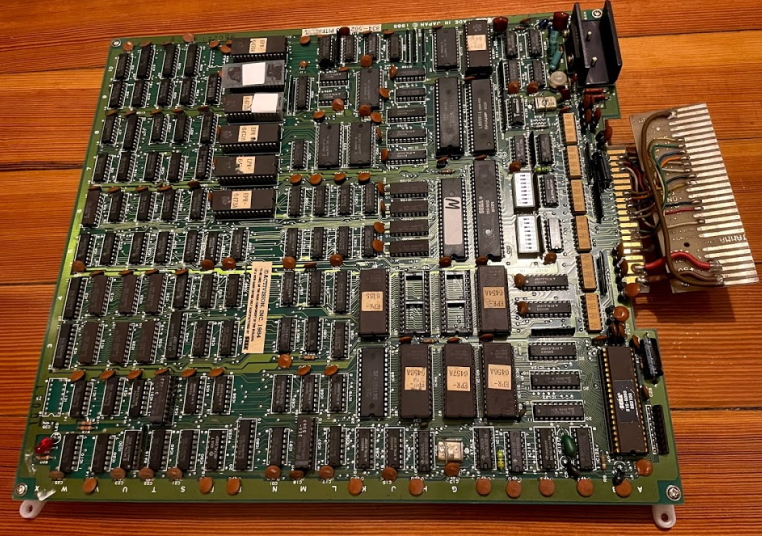

Sega utilized their System 1 hardware; this had been their top-of-the-line hardware in 1983, and remained such in early 1985. However, the same year would see the release of the Sega System 2, and the Sega System 16, and most importantly the “Super Scaler” Hang-On and Space Harrier, so by the end of the year already Pitfall II would look pretty dated. Still, the System 1 has a pretty nice look to it, with plenty of color.

I don’t want to go into the Sega System 1 in detail here; with any luck, I’ll have a future blog post to talk about it. Notice that it’s not a JAMMA board, but this particular version has had a JAMMA connector somewhat haphazardly connected. I didn’t put that there, and am considering removing it; sure it works, and I will need some sort of adapter, but it’s not very elegant.

Get to the game already

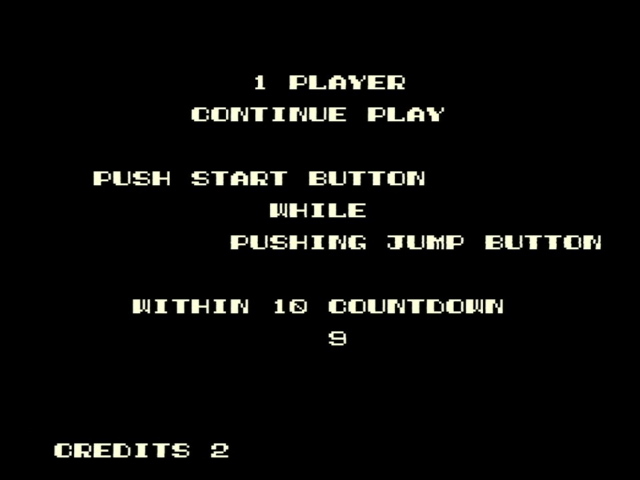

You’d be forgiven for thinking Pitfall II was actually just a port of Pitfall!. Like the original, there are just two levels and one exit on the right side, and Pitfall Harry has lives, denoted by the hats in the lower corner. There’s even a timer, which at 3 minutes is much more aggressive than Pitfall!’s twenty, but works on similar principles.

There are even vines to swing on, and Harry does a little Tarzan-yell, iconic features of the Atari 2600 original that did not make it to Crane’s sequel.

Starting with a Pitfall! sequence made sense for Sega; the original game, while iconic in the west, was less popular in their home market of Japan, where the localized Atari 2800 was an infamous flop. So including these sequences is a good way to introduce Harry to a new audience.

In any case, once you enter the cavern below (and you’ll want to; collecting treasures is the only way to increase the time limit), you see a hint of vertical scrolling to come.

Despite the glimpses of the world below, the entire first phase of Pitfall II, however, is a mostly linear jaunt across horizontal screens.

This is the right call for an arcade game; Pitfall II on consoles and computers can take it slow at the start and build up to more action as you enter the caves. But on arcades, you need to get the player hooked fast. So with this Pitfall!-like segment, the player picks up the rules of the game and also probably dies a few times.

The Linearization of the Lost Caverns

At the end of the first segment you collect a key. And what happens when you collect this key?

A hole in the floor opens up, and drops Pitfall Harry down! And the music changes; still a remix of the Pitfall II theme, but now it’s a minor key remix, making up for the lack of the dynamic music seen in the original.

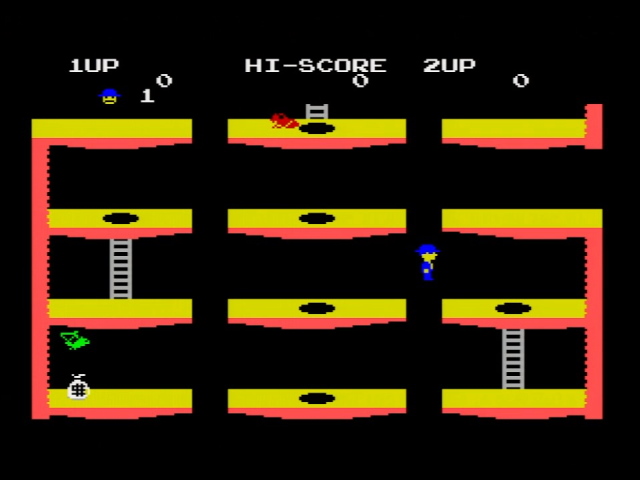

The lost caverns of Pitfall II’s arcade incarnation are divided into three subsegments. In this and the next segment, you need to find a certain key treasure, and then find a key that will drop you into the next segment. Then finally you find the crown, which ends the game. Quickclaw and Rhonda are nowhere to be seen in this one.

This first segment is the most similar to the original game, with its long shafts with balloons and vertical shafts. Still, falling stalagtites prove a different challenge than the bats and birds of the original. The next segment introduces minecart puzzles, and then finally deep in the sanctum is the most maze-like of the three.

The lost caverns world is a continuous map, but you only have access to one third of it at any given time. Getting a key opens a hole in the floor, cutting you off from the prior segment; this is a significant change from the original, and helps prevent you from getting completely lost.

As for life, the same rules apply underground as on the surface. You have a timer that you can refill by collecting treasures, and a limited amount of lives. Continues are possible if you pay, and revive you in the vicinity of where you died; therefore, if you’re not playing this in an arcade, this version is actually much easier than the original.

Overall, Pitfall II: The Lost Caverns is a good example of a strong arcade port. Gameplay is streamlined, while the more powerful arcade machine is used to provide additional variety the Atari 2600 version just couldn’t do. Even though it’s massively overshadowed by Sega’s later 1985 releases, I’m sure it got plenty of quarters. Pretty much everyone was overshadowed by Space Harrier.

Pitfall II: The Game The Game The Game

Fun fact: in 1985 Sega didn’t just do arcades; they had a home console too. No, not the Master System; while that console came out in 1985 (at least in its original Japanese form, the Mark III) and was very well-suited to ports from the Sega System 1, it didn’t come out in October. The game we’re talking about came out earlier; I’m not sure of the exact date, but a mini strategy guide I have has a date of August, so that at the latest.

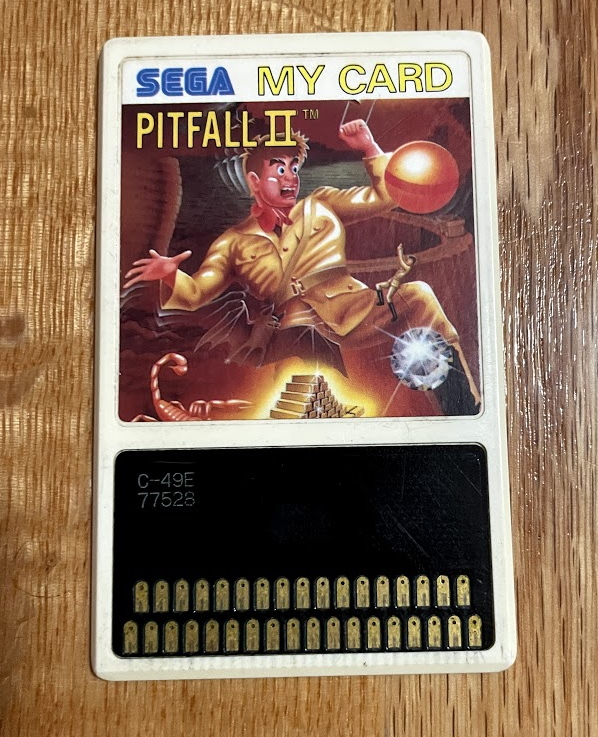

Yep, we’ve come back to the SG-1000, the console version of the SC-3000. And while Pitfall Harry here’s not looking very similar to his arcade flyer (probably for the best), Sega didn’t just port over the original game, and the SG-1000 wasn’t powerful enough to reproduce the System 1. Instead, they created an entirely new, third Pitfall II.

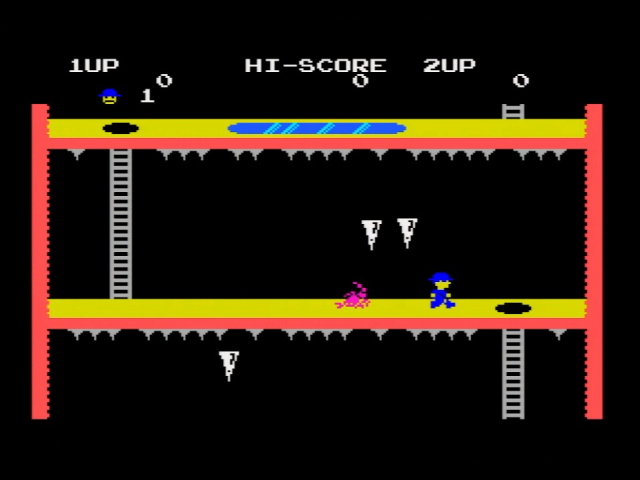

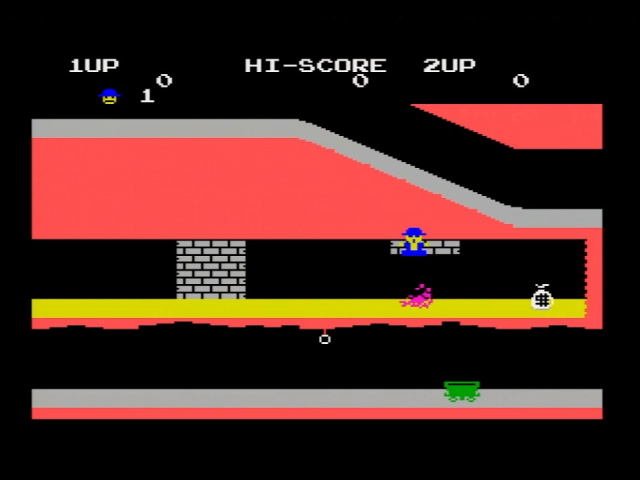

The SG-1000 is, hardware-wise, almost identical to the ColecoVision, and differs only in the sound chip and in having less memory to the MSX. Therefore, it’s worth comparing this game to the MSX version that I showed above. They were both released in the same year in Japan even. Let’s look at how both games start.

There are definite similarities. But notice that while the original Pitfall II placed a character you had to collect at the bottom, and hinted at the vertical nature of the adventure, SG-1000 Pitfall II puts an entirely closed room; a mystery the player just doesn’t get to know about yet, but hopefully will file back in their mind.

Delinearizing the Linearized Caverns

The SG-1000 version of the game starts with a Pitfall!-style linear segment, though it’s much shorter than the arcade one, getting quickly into the lost caverns. And the caverns themselves are no longer divided into linear segments; while they follow the basic structure of the arcade version, the same music plays throughout, and keys no longer exist.

Like the arcade version, the minecarts have made the transition, and Quickclaw and Rhonda have been cast aside in favor of certain key treasures you have to collect. Also, like the arcade version, you have limited lives and respawn near where you die, but you can’t continue. This makes this probably the hardest version of Pitfall II, and the farthest from the generous checkpoint vision.

The biggest change from the arcade or David Crane’s version, though is that crystal ball at the beginning of the game. Getting to where the crown was in the arcade version nets you only a key, and you must back-track, escaping the caverns. It’s a natural extension of the game.

Music

One place I do have to complain is the music. As noted, one track plays throughout the game; no remixes, and no dynamic music. First off, let’s take a listen to the MSX music. Note that the MSX1 sound chip, the AY-3-8910, is fairly similar to the SN76489 the SG-1000 uses, though admittedly not identical. A ColecoVision would be a better comparison, but I don’t have one of those.

It’s not as good as the POKEY rendition above, but it’s pretty passable. (What isn’t passable is my audio capture, for some reason this was very hard to get without a ton of noise.) You can hear both the “triumphant” and “neutral” segment. Now let’s compare to the SG-1000.

Not only is it mostly hanging out on two voices (which does make sound effects less likely to impinge upon the main theme), but the song only contains the “triumphant” section, on infinite loop. The lack of variety is definitely disappointing, though, as we’ll see, it could be worse.

Sega does what Activis…don’t

Overall, the SG-1000 version of Pitfall II is very interesting as a conversion; it takes ideas from both the arcade and console versions. The limited lives are annoying, but it was standard for console games of the time, and it is possible to get additional lives by reaching certain scores by collecting treasures.

Technically, no system got both versions as an official release, but while sales numbers are hard to come by, they were on the market in the same time in Japan.

Revising a revision of a revision

This section added 9/4/2021.

But we’re not done with the SG-1000 port of Pitfall II just yet. Remember when I said that it looks just awful on the Master System? Well, that applies to the Sega Mark III as well; and the Mark III was released months after Pitfall II. Remember, the arcade version of Pitfall II was a pretty big success even if it was overshadowed by Sega’s later 1985 works, and SG-1000 games remained on the market. So having a poor version of Pitfall II simply wouldn’t do.

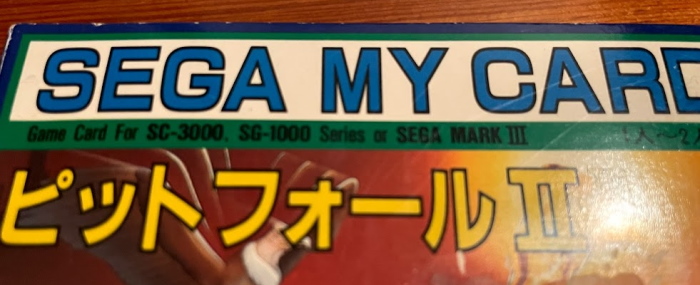

Thankfully, Sega released a revision. I happen to have it boxed, and you can see it on the left. It’s in better shape than my revision 0 card on the right I’ve been using up to this point. We tend to call these revisions 0 and 1; this is just a ROM dumping community standard as far as I know, I don’t think Sega ever officially acknowledged this.

Since I don’t have a boxed version of revision 0 of Pitfall II, I’ll direct you to SMS Power!, which has a scan. The most important difference, however, I’ll show zoomed in.

You might wonder why it doesn’t mention the Othello Multivision, or the Pioneer TV Video Game Pack SD-G5, other SG-1000 systems. Don’t worry! They’re mentioned on the back.

But more importantly, what does optimizing Pitfall II for the Mark III actually mean?

The Caldor Rainbow

We’ll start by running it on my trusty MSX.

It’s a pretty subtle difference. Most notably, look at Pitfall Harry’s skin color, and the ground (they’re the same color). Notice that the revision 1 is less saturated.

Why is this? Let’s take a look at the TMS9918 palette. Note that I’m still using the MSX for this, so this is an approximation. Really, the best option would be to use an RGB-modded TMS9928A system. Specifically, on the MSX things are a bit more saturated, but not nearly so much as the Mark III, as we’ll see. (I’m using Bifi’s PALEDIT for this.)

As you can see, the two shades of yellow are pretty close. But what happens if we try to approximate the Mark III palette?

Turn around, bright eyes

Essentially, the colors are now fully saturated. Generally, colors only have red, green, or blue components, and mixed colors are gone. This is likely because the Master System uses a 6-bit RGB palette, with only 2 bits for each of red, green, and blue; the TMS9918A palette is hardcoded into the chip and therefore TI could use any values of resistors they wanted. (The MSX2 uses the Yamaha V9938, which uses 9-bit RGB, which is why it can get closer)

So now, let’s take a look at those two revisions when running on a Sega Master System. Remember, you’ll need to use a Japanese console or a BIOS-modded western console, since SG-1000 games don’t have a header or trademark info.

Obviously aesthetic judgments are arbitrary, but I’d say it’s a definite improvement. The very bright saturated colors almost give it an RGBI look; though not quite, as you can see giveaways like the three shades of green. As for the dark yellow, well, there’s a reason that IBM changed it to brown for the PC; it’s just not a pleasant color to my eyes anyway.

As far as I can tell this is the only difference between the revisions; I also took a look at other SG-1000 games known to have revisions, and couldn’t find anything equivalent. This seems to have been unique to Pitfall II, which as noted, came out just before the release of the Mark III. To my eyes, at least, this implies that the Sega version of Pitfall II was pretty successful in Japan to warrant this kind of effort. (Well, successful for an SG-1000 game, anyway)

Pony rides right off into a canyon

And yet we’re still not done yet. There was another company that decided to build a new game off of the skeleton of Pitfall II. Unfortunately….

Sega’s rights to Pitfall don’t seem to have extended beyond the arcade and their own platforms. Instead those rights, including selling the MSX ports of Pitfall and Pitfall II in Japan, went to Pony, Inc. (specifically, their computer publishing division “Ponyca”) Pony, Inc., known as Pony Canyon since 1987, is a part of the massive Fujisankei Communications empire, produced the Neo Geo Gals Graffiti video I used in my composite video upscaler comparison, and is still in business today. However, they don’t publish video games anymore.

The MSX was popular in both the west (primarily Europe) and the east, but many Japanese computers weren’t popular outside the country, and so Activision didn’t have pre-existing ports. One of the most popular was the NEC PC-88 series (don’t confuse it with the PC-98!), and another machine that in late 1984/early 1985 could be excused as being seen as a Japan-only oddity was Nintendo’s “Family Computer”. (After all, we all know consoles are dead in the United States!)

And so while Pony owned the rights to sell Pitfall II on the Famicom and PC-88, if they wanted to, they’d need to port the game themselves. They decided to make this instead.

Super Pitfall is a fairly infamous game. Pitfall II was so good! Why would Pony saddle us with this excuse of a game? Well, let’s not trot ahead of ourselves.

- Pony only had the rights to David Crane’s Pitfall II. This meant that they couldn’t use any of the additions from the arcade game, while they still had to compete with Sega’s release on the market.

- Crane’s Pitfall II was an amazing game in 1984. Super Pitfall had to exist in a 1986 Japanese gaming market. Super Mario Bros. had redefined the platformer genre, and The Legend of Zelda had redefined the adventure game.

Super Pitfall, like the original Pitfall II, tasks you with collecting the Raj diamond, Rhonda, and Quickclaw. However, it also tasks you with collecting items to open gateways, to unlock the cage containing Quickclaw, and to reverse the spell that turned Rhonda to stone. Finally, like the SG-1000 version of Pitfall II, after you do all this you also need to escape. Increased depth is added not through more gimmicks like minecarts, but with a larger world, and multiple sub-worlds.

Pony wasn’t necessarily wrong to decide to build a new game based off of the bones of Pitfall II rather than a straight port; it sounds pretty good on paper. The problem with all this is really just the way they went about it.

So, what went wrong?

We’re hooked! On Micronics!

We’ll start with the first problem, though honestly I think it’s the least important. The port of Super Pitfall (a port, because the game was released first on PC-88, apparently developed by Pony in-house) was not coded by Pony, but by a contract developer they hired called Micronics.

Micronics has a reputation for, for lack of a better word, “jank”; they also made, among many other games, the ports of SNK’s Athena and Capcom’s Ghosts ‘n’ Goblins to the NES. The company itself is not well-known, as contract developers tended to remain anonymous, but is rumored to have just one developer; and honestly, considering their prolific output in the NES era, if that’s so that coder was probably one of the best out there. But under those circumstances how can you make gold?

Pitfall Harry’s walk cycle is jerky. Random chunks disappear and reappear from sprites for a frame or two. Sometimes you get stuck on a ladder. When you collect a pile of gold bars, you just collect it all in one and it disappears, often without even a sound effect. Collision detection is all over the place. Loading times when starting the game or after a death are long and inconsistent. The music is a remix of the Pitfall II theme, but it’s hardly recognizable, and again doesn’t have the mood changes of the original; this time, it’s only the “neutral” segment. (Subcaverns do have separate themes)

Note: For fun, I decided to use my Famicom with a “stereo” mod; this hard-pans the square waves to one side, and the noise and triangle to the other. If you’re wearing headphones, be warned; I know hard-panning bothers some people.

But honestly, I want to give Micronics a break here. Because contract development firms develop what they’re told to, and everything was signed off by Pony; technical bugs like this are one thing, but Super Pitfall would still be a bad game without these bugs. And because the real flaws are in the design, and it’s unlikely Micronics had much say there.

Flipping out

Super Pitfall on Famicom is not a direct port of the PC-88 version. The PC-88 version was flip-screen like Pitfall!; there was no scrolling, not even up and down. Instead, the world consisted of a grid of rooms.

The NES is particularly well-suited to a game like Pitfall 2 that only scrolls in one direction; it has enough nametable memory for two screens worth of graphics. That lets you do smooth horizontal or vertical scrolling, but not both. (I talk about nametables a little bit in my NES coding article, but Aspect Star “N” doesn’t scroll, so these limitations weren’t important to talk about)

Super Pitfall scrolls in both the x and y directions, and it’s one of the earliest games on the system to do so; along with Micronics’ earlier Ghosts ‘n’ Goblins port. This is quite a technical accomplishment! Probably a lot of the technical “jank” this game has to deal with comes from the difficulties of creating a full large scrolling map, with only a limited UNROM motherboard without additional chips or additional nametable RAM to help out.

It was probably a lot of effort and late nights to get that to work. So it’s a real shame that Super Pitfall is actually worse off for it.

Let’s look at the start of the game. Oh nice, a ladder! Let’s check it out.

I can’t see what’s below! If this was a flipscreen, you could imagine now seeing the perspective of the room from the top, whereas you’d also see more of the pyramid when on the surface. It doesn’t take advantage of the free-scrolling world at all.

And what happens if you take a leap of faith?

You die. This will also teach you pretty quickly that this game isn’t like David Crane’s Pitfall II; instead, like the Sega SG-1000 version, it has a limited life counter. But it also shows that even though the game has this expansive scrolling world map, its levels are designed in such a way that they would seem to make far more sense in a flip-screen game.

What’s particularly baffling here is that the room where you climb down the stairs to get killed by spikes isn’t even in the PC-88 version; instead, there’s a room with a lifebar– another nicety that Pony(ca) and Micronics decided NES players didn’t need. This sort of thing makes me wonder if this port was also going to be flip-screen at some point; I guess unless the Micronics developers decide to speak out, we’ll never really know.

It’s a secret to everybody

In 1984, Namco released The Tower of Druaga, which in games evolution is basically the midpoint between Pac-Man and The Legend of Zelda. While it didn’t receive more than a test market release in the US, it was a major hit in Japan. Unfortunately, I feel like you could also blame it for ruining game design for a generation.

The most frustrating element of that game is that each level contains a secret item; to collect that item, you need to perform some unspecified and completely untelegraphed action. Maybe it’s kill a certain enemy. Maybe it’s stand on certain tiles. Maybe you have to perform a blood sacrifice to the dark god Namcot on the full moon while on level 31. And some of these objects are necessary to beat the game; others actually hurt your character.

In a paradoxical way, it worked because it was a hit; so many people played it in Japan that they could trade the secrets or methods they heard with other players, and eventually the excellent Famicom port also served as a tool they could use to figure things out without dropping 100 yen (yeah, arcade games were more expensive in Japan) per play. But it also seems to have convinced many Japanese developers that the secret of good game design is to reveal nothing.

Okay, okay, this wasn’t all Druaga’s fault. Other motivations for hiding items without any clues included padding out the length of games (in part to justify the high cost of cartridges), and for games that would be released in the west, making sure games were too long to be played over a rental. (Video game rental is essentially illegal in Japan, so it’s not a concern there) It also sold strategy guides. We’re not here to attack Druaga anyway; despite its obtuseness, The Tower of Druaga is fun, and its hidden items have a lot of variety in how you unlock them. Not so for Super Pitfall.

Nearly every single object in Super Pitfall, from portals, to the exits of portals, to all the items you need to complete the game, and even ammo refills, is invisible, and can only be revealed by jumping in a certain place. Look at this ammo refill right near the beginning of the game. And now combine this with the game’s clunky collision detection and you really have a recipe for just constantly jumping everywhere like some kind of bunny rabbit. Only gold bars are visible without doing this.

Now, there are some hints here. For example, dead-end paths are likely to have something, and it is a platformer, so you’re probably going to jump pretty often anyway. But then you have things like the portal that requires you to jump into a particular enemy; a totally unfair twist that even The Tower of Druaga wouldn’t try.

Activision couldn’t see this coming

Super Pitfall was released in Japan in 1986. That was the same year the NES became generally available in the United States, and the revival of the video game console industry in North America really kicked off. Activision was under the leadership of Bruce Davis, who industry history books really don’t paint a pretty picture of. He drove away talent like David Crane, shut down Infocom, renamed the company ‘Mediagenic’ to more effectively sell business software, and even worse, didn’t even end up making money, bringing Activision to its 1991 bankruptcy. The modern company Bobby Kotick formed out of the rubble barely has anything in common with the company in the late 80’s.

With that narrative in mind, it’s hard not to see the US release of Super Pitfall, Activision’s first NES release (and for nearly a year, its only), as anything more than a cynical cash-in motivated by a realization that consoles were back, and didn’t they license their most popular franchise to some Japanese company? Did they even play the game before releasing it in the US? They couldn’t even be bothered to change the extra life symbol away from Fujisankei’s logo!

This isn’t quite fair to Activision, though. They also ported the game to the Tandy Color Computer 3 (well, they farmed the port to Steve Bjork of SRB Software), which wasn’t released in Japan, and that port even has an option to make items visible and give Harry unlimited lives. (It also uses a “red eye” for the extra life, according to the manual) Unfortunately I don’t have a CoCo 3, but you can see some footage of that version here.

In any case, America got Super Pitfall near the end of 1987 on the NES, and other than some copyright notices it was pretty much unchanged from the Japanese version. It came out after games like Metroid, which handled the exploratory platformer with a bit more grace and pizazz; but it was still pretty successful for Activision. The Pitfall! name still had some cachet, though games like this certainly wouldn’t be good for keeping it.

A sequel?

Super Pitfall was successful enough that Activision even planned a sequel. Thankfully, perhaps, Pony Canyon or Micronics were to have nothing to do with this, but nor would it be developed in-house or even in the United States; in fact, it was just a rebadge of Sunsoft’s Atlantis no Nazo, a game that predates Super Pitfall even in its Japanese form. It was probably seen as a decent option for a Pitfall branding just because of its cute explorer protagonist and non-linear nature.

Atlantis no Nazo is an interesting game, a post-Super Mario Bros. creation that, while not appealing to everyone, does have a strong exploratory element, with a maze of numbered stages connected by doors. It’s also a bit unfair and has a confusingly limited method of attack, so Super Pitfall fans who could get over the visible items probably would enjoy it. It’s not everyone’s cup of tea, but it has some fans, and it doesn’t feel like the game is on the verge of falling apart.

I don’t think anyone knows why this release didn’t happen; it might just be another victim of Activision’s slow collapse over the course of the late 1980s, the chip shortage that delayed the US release of games like Super Mario Bros. 3, or maybe a 1986 game was just too old. Atlantis no Nazo remained a Japanese exclusive. It’s a shame that we never got to see the people who made the 1989 Galaxy Force box for the Sega Master System try to hype up this game.

We’re not done yet!

Super Pitfall is in some sense a video game tragedy. With its huge free-scrolling open world it’s definitely ambitious (even Metroid only scrolled one direction at a time), but the flaws of its design and the bugs of its coding prevented it from reaching its full potential.

So such a game got some sympathy from a passing ROM hacker, and we have this amazing piece of effort: NESRocks’ Super Pitfall 30th Anniversary Edition.

This is honestly more effort than this game could be said to deserve, so it’s really neat to see. Definitely check it out; not only is it a graphics overhaul (a new Pitfall Harry that splits the difference between Super Pitfall and Atlantis no Nazo, along with background art), but it also removes many of the elements I complain about above: items are no longer invisible, the game features saves to ease the pain of limited lives, the game has a new soundtrack, the world is mostly the same but rough edges have been filed down, and many (though not all) bugs and jank have been cleaned up.

It does show what Super Pitfall could have been; of course, it does so in part by adopting the advanced MMC3 mapper chip, which Micronics didn’t have access to in 1986. Labors of love like this are always nice to see; even David Crane approves. (Of course, like all fan projects that hang out past the line of copyright, we can only hope that Activision never decides to smite it)

The fall of Pitfall

Activision went bankrupt in 1991; the modern company has little connection to the old one. So it’s perhaps not a surprise that while Pitfall did enjoy a brief revival of the 90’s, it too had little connection to the older games. Pitfall, it seems, is best left as a nostalgia game; and mostly centered on the first one.

Super Pitfall gets released occasionally on things like Virtual Console, and the Atari 2600 Pitfall! and Pitfall II show up in pretty much every Activision collection, so they’re easy to get ahold of. Unfortunately, the Sega versions of Pitfall II seem to be unavailable in a modern form; likely due to the rights being divided by Activision and Sega; that’s a shame, as it’d be nice to see a re-release. Those PCBs are definitely not that easy for most people to get ahold of for a legal playthrough.

I hope you all enjoyed this walk down video game history. And if you’d ask me which version of Pitfall II is my personal favorite, well, I’d say, look over there! A thing!

…but it’s definitely not Super Pitfall.