The games Nintendo didn't want you to play: Tengen

Recently, I took a look at Nintendo’s MMC line of mappers, and some other boards. All boards for the NES’ western releases had to be manufactured by Nintendo, and so they generally met certain standards set by Nintendo. But these rules were enforced by technology, not by law. And the company that had previously killed the American game industry decided to break those rules. Madness? No. This… is Tengen.

Tengenerations

We saw Tengen in the NES blog post, where they released the games Gauntlet and R.B.I. Baseball using the DxROM family of circuitboards, which used a Namco-made mapper chip. Tengen’s licensed period, however, only seems to have lasted less than a year. Their first title, R.B.I. Baseball, came out in April 1988, and in December 1988, Tengen announced that they would break with Nintendo and manufacture games themselves, with a classy black trade dress with larger art.

The Atari 2600’s demise is generally blamed on a glut of low-quality cartridges, caused in part by the console’s openness to unlicensed games. (As Atari didn’t expect anyone to try to become a third-party developer; the concept didn’t even exist yet) As a result, Atari collapsed in a flood of red ink; its home consumer division was sold to Jack Tramiel, who mostly wanted the brand to promote his ST computer and replaced most of the staff. Avoiding that fate is the reason Nintendo put the licensing regime in place.

The arcade division, which was doing better (though the American arcade market was already beginning its decline with the end of the Golden Age) remained in Warner’s ownership and kept its staff, but adopted the name Atari Games. Since Tramiel’s Atari Corporation owned the right to the name for home products, Atari Games, arguably the more direct descendant of old Atari, had to come up with a new brand. And that brand was Tengen.

Of course, Tengen wasn’t intending to sell low-quality games like those that had plagued the 2600. They had Atari Games’ library of arcade hits (like Gauntlet), as well as NES games from their sometimes-parent company Namco, and rights to arcade titles from other companies that had opted out of Nintendo’s licensing world, like Sega. That’s what makes Tengen stand out from other companies that would make unlicensed games like Color Dreams. This was a serious attempt by big names in the business to break Nintendo’s licensing.

Follow the Rabbit

The other thing that makes Tengen stand out is how they broke the Nintendo’s lockout chip. Modern consoles maintain their lockout using cryptography. But in the 1980’s, that would get your console classified as a munition, and the NES’ 1.7MHz CPU would struggle to implement anything regardless. Plus, cryptographic locks had no legal force at the time; this wouldn’t be the case in the US until the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

So instead, Nintendo developed a small microcontroller, which implements a program of sending random numbers back and forth. The microcontroller in the console compares with one in the cartridge, and if their numbers don’t match the expected pattern, it resets the console every second, preventing gameplay. The chip is configured so the program can’t be dumped easily, and if you do dump it, the program is protected by copyright law.

Here’s Camerica’s 1992 release Micro Machines. You might notice some circuitry in the corner; what this is is actually something we’ve covered on this blog before, a charge pump that produces a negative voltage from the console’s 5V input. When the console turns on, a negative voltage spike is sent down the reset line of the lockout chip, frying it long enough to break its program and cause it not to reset the console.

Why is there a switch? Because the way this circuit is designed, if there is no lockout chip present, it will just draw large amounts of power from the console until something fails. And in 1993, Nintendo would release a variant of the console that had no lockout chip. Prior to this, Nintendo would make other adjustments to the NES to try to prevent methods like this; specifically, diodes were placed to break earlier Color Dreams attempts at frying the lockout chip’s data lines.

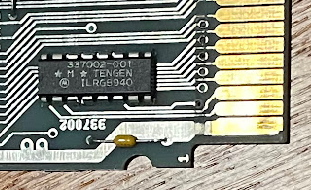

Far back in 1988, Tengen seems to have recognized this option existed, but was too much of a hack. Plus, a negative charge shock could in theory risk damaging the console and leaving Tengen and its parent, Atari Games, liable to significant damages. So they made their own clone, the “Rabbit”, which actually communicates with the console side, and tricks it into thinking it’s just a regular Nintendo chip.

How did they do it? As it turns out, crime. Unable to reverse engineer the chip, Tengen convinced the United States Copyright Office to hand over the source code of the lockout chip, claiming it was necessary for a lawsuit. With the code in hand, Tengen could make their own clone with ease. And Tengen was going to sue Nintendo for antitrust violations, so they probably figured they could get away with it.

The Nintendo-Tengen saga ended in an out-of-court settlement in 1994. That year was the same year Tengen disappeared, as Atari Games was subsumed into Time Warner again, becoming part of Time Warner Interactive. While there were injunctions in between (it seems they may have been pulled in 1992 and I’m not sure if that was ever reversed), this means that for much of the NES’ most popular period, Tengen games were on the market too, if you could find them. Let’s take a look at some of them.

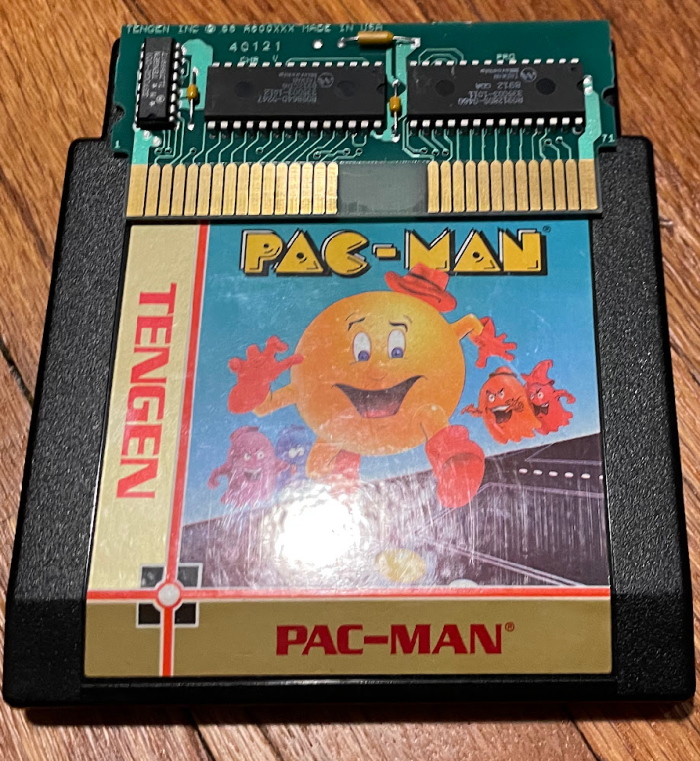

Pac-Man

Namco’s Pac-Man port is an NROM-128 game, the simplest circuitboard that Nintendo sold in the west: 16kiB of program ROM, and 8kiB of character ROM. (My game Aspect Star “N” also meets these limited requirements.) But despite that, the game seems to have one of the most convoluted release history on the console. See TCRF for more details; it had two Namco variants in Japan, and three North American releases: a licensed Tengen, this unlicensed Tengen, and then in 1993, Namco would release it under a license again.

So here’s Tengen’s Pac-Man. This board is pretty much identical to Nintendo’s NROM-128, with the two ROM chips and the lockout chip. Which makes sense; this is pretty much exactly the same game as Tengen released licensed a few months before, just without claiming to be licensed.

The only other mapperless game Tengen would release would be their take on Ms. Pac-Man. Surprisingly, this is a completely different game than Namco’s licensed version in 1994. (However, it is very close to the Genesis and Super NES versions, also by Tengen)

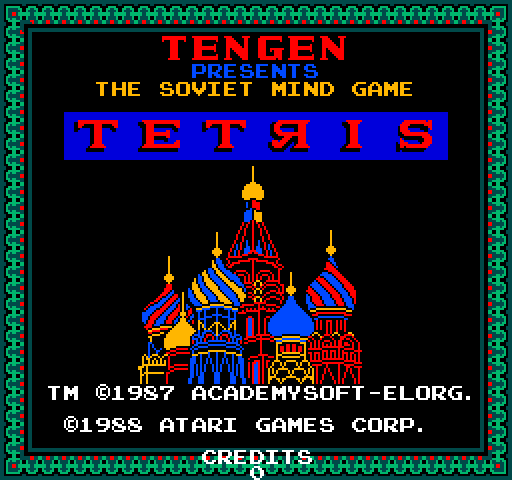

Tetris

When many people think Tengen and the NES, they think Tetris. As I noted in the story of Bloxeed, the rights to Tetris are a downright mess. But one thing is for sure; Atari Games definitely had the arcade rights to the game, which they released in 1988. They definitely thought that came with the console rights, and planned a huge launch for 1989. Nintendo and Bullet-Proof Software outmaneuvered them, Tengen’s version was recalled right away, and is now quite rare. End of story, right?

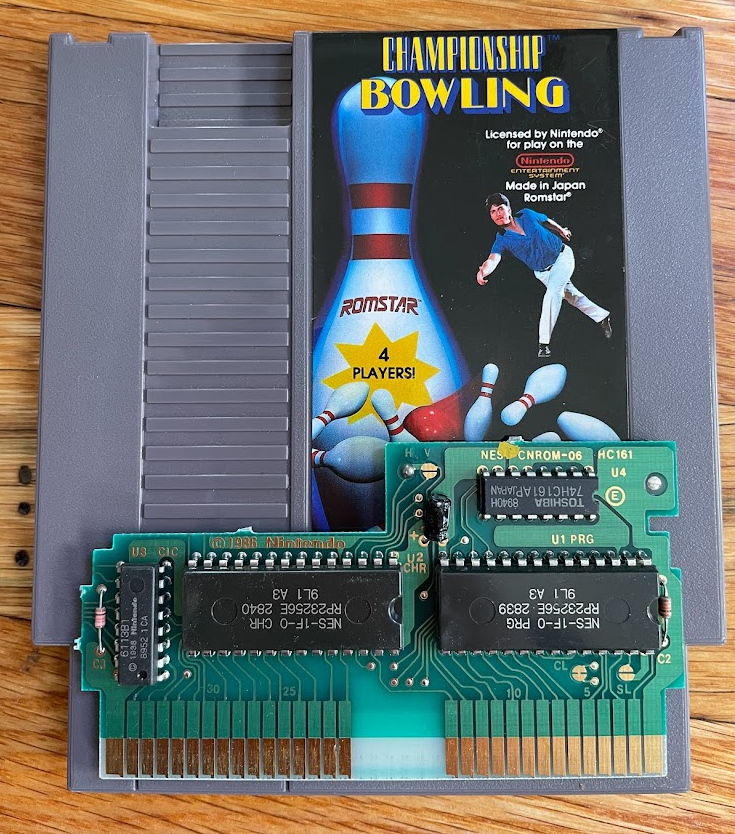

Tengen’s Tetris uses a unique circuitboard; the game is expensive enough that I don’t have it here to show you, but it’s actually identical to the standard Nintendo CNROM, a discrete-logic mapper used in games like Championship Bowling. Generally, Tengen seems to have preferred ASIC mappers, so it’s interesting that this particular game used discrete logic; perhaps it’s because they expected it to sell in high numbers and needed chips they could quickly get ahold of?

Another interesting thing about Tengen’s Tetris is that it may actually be the fourth Tengen game to be licensed by Nintendo. What are you talking about, Nicole? As it turns out, Tengen test-marketed their Tetris using Nintendo’s arcade VS. platform. As far as I can tell, this was all official and above-board, and was prior to the December 1988 break between Tengen and Nintendo; I’m happy to be corrected– it’s a bit odd that this version of Tetris uses the Tengen name when Atari had full rights to use it in arcades.

The screenshot is from the MAME emulator.

MIMIC-1

Back in the last article, we looked at Gauntlet, whose licensed incarnation used a Namco 109 chip. This chip provided very flexible CHR and PRG banking similar to Nintendo’s MMC3, but that’s all it did, without support for software-controlled mirroring, IRQ-timers, or other advanced features that Nintendo would add to their version.

Since this used a Namco chip, and Tengen was quite friendly with Namco (after all, Namco owned a chunk of the company), you might expect the Namco chip to be used in their circuit boards too. You’d be wrong.

Like the Nintendo-manufactured version, this features a lockout chip (a Rabbit), a 74-series logic chip, program and character ROMs, a VRAM chip for four nametables, and a final chip for mirroring. But there are differences too. For one thing, the Tengen board has no solder mask. What’s the deal with that, Tengen?

The more interesting thing is that Tengen manufacturered their own clones of the Namcot 109 chip. Usually called the MIMIC-1, it has all the capabilities of the Namco chip, but uses a more normal pin spacing and a larger package. As far as I can tell, all Tengen boards using this chip use the Tengen-manufactured version. Being part of Atari Games, of course Tengen had plenty of skill making their own chips.

MIMIC-1 was the most common Tengen unlicensed mapper, being used in games like Super Sprint (above), the R.B.I. Baseball series, Pac-Mania, Toobin’, Vindicators, and more.

So far, we’ve seen Tengen boards that don’t actually offer anything new to the NES. The MIMIC-1 is just a clone of the chip used on DxROM circuit boards. From Tengen’s perspective, of course, they likely did save money manufacturing in-house and avoiding Nintendo’s licensing. But in the United States, antitrust law is supposed to be about consumer benefit.

After Burner and ROM nametables

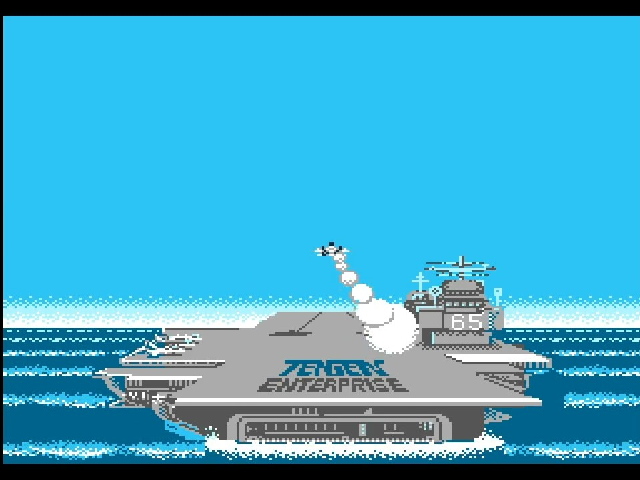

Probably the strongest case for Tengen that Nintendo’s licensing hurt consumers was their release of the Sega arcade title After Burner, which they released in 1989.

After Burner is a fast-paced arcade-style shooter where you pilot a fighter jet, taking off from an aircraft carrier and fighting enemies. And this port is honestly really good, far better than an NES game based off of After Burner has the right to be. And it’s by one of the best developers for the NES: Nintendo licensee Sunsoft, who made Blaster Master, Spy Hunter, Batman, and a whole host of titles.

It even maintains one of the key effects of the arcade game; the whole viewpoint swinging around at dramatic angles as you move your craft while rapidly animating forward. It gives a convincing impression of swinging around at high speeds, even though the NES of course does not come with the full cockpit option the arcade game had.

So how did Sunsoft do it? After Burner uses a custom chip, the Sunsoft-4. Now, the Sunsoft-4 was not used in any games manufactured by Nintendo; this game is the only time it made it outside of Japan. (However, the later Sunsoft-FME7 was used in the Nintendo-manufactured game Batman: Return of the Joker and several more in Europe) Here, Tengen seems to have manufactured their own version.

The most interesting thing about the Sunsoft-4 is the use of ROM nametables. Up until this point, we’ve assumed that nametables are in video RAM. Accessing video RAM is slow; you can only do it in VBlank and have to go through the PPU’s registered. NESdev recommends planning to have only 160 bytes changed in a frame, plus the DMA for sprites.

One full nametable, though, is 960 bytes, assuming you give them all the same palettes and don’t need to change the attribute tables (if you do, then you need a full kilobyte). So how does After Burner swing the whole screen like that? Changing halfway through a frame would produce a pretty ugly transition effect. On the other hand, though, After Burner’s nametables are highly predictable. They don’t change based on where you are in the level, just based on the position of your plane. This makes it a perfect usecase for storing them in advance. The Sunsoft-4 can include precomputed name tables in ROM, and with 128kiB, you have 128 nametables, more than enough to give After Burner its rapid-fire changes and fast animation.

Now, the thing is, we don’t know why Sunsoft and Tengen partnered for this game. It’s unlikely it was because of Nintendo and Sega, despite what you might think; Sunsoft was licensed by Nintendo in Japan. (In Japan, the licensing program was much less strict, and participants could still manufacture their own cartridges) Like Gauntlet, After Burner requires a dedicated circuitboard design just for it. So it’s definitely possible to see how Nintendo’s hefty licensing fees would wipe out the potential for profit.

One thing worth noting, though, is that Sunsoft’s Japanese release of After Burner II (despite the name change, the same game) is substantially upgraded, with things like the sweet title screen animation above that the US didn’t get. It seems that Tengen put some time pressure on the team, resulting in an unfinished version of After Burner making it to America, while Sunsoft gave their developers a little more time to finish the game before releasing it in Japan. It wasn’t all sunshine and roses at Tengen.

Stop: Rambo time

Cut off from Nintendo, Tengen couldn’t use the MMC3, and had to make their own iteration of the Namcot 109 to get those wonderful extra features.

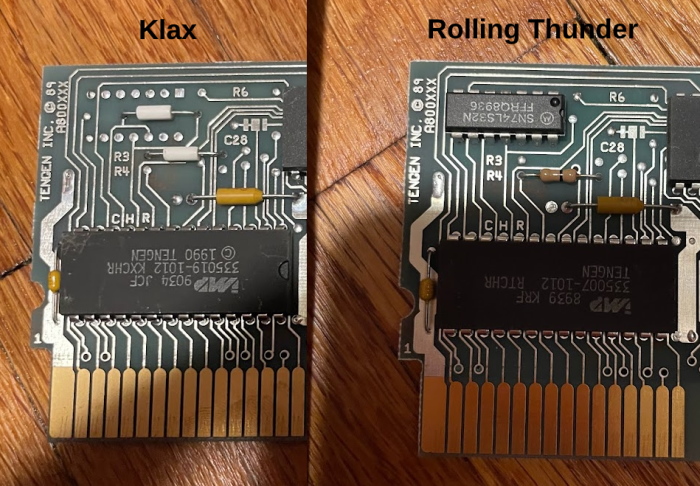

So anyway, most of the time, Tengen had to make their own iteration to get some wonderful extra features. And this chip is called the RAMBO-1. Since we have time, let’s take a look at 1990’s Klax.

One interesting thing about the RAMBO-1 is that it includes the Rabbit chip on-die. As far as I know, Nintendo never combined the mapper and lockout chip into a single chip.

The NES Klax is a pretty decent take on the falling-tile arcade game. It’s also very colorful and varied, with lots of tiles on screen. Tiles in the literal sense of 8x8 PPU tiles as well as the sense of the falling tiles in game. RAMBO-1 offers a similar scanline counter IRQ to MMC3.

It’s so similar to MMC3, in fact, that Hudson Soft licensed the Tengen version of Klax for release in Japan, and used the Nintendo chip for it. The game uses very careful timing to constantly switch out the screen for things like messages, even mid-scanline. Raster effects like this generally require all of the CPU’s time, but Klax’s game logic is relatively simple, so it can do things like this.

The RAMBO-1 counter is a little bit more advanced than MMC3; it can also count CPU cycles instead of scanlines. If timed from an NMI to keep things synced with the PPU, they can be used for similar effects; in fact, the Famicom Disk System version of Super Mario Bros. 2 uses a CPU counter for its status bar.

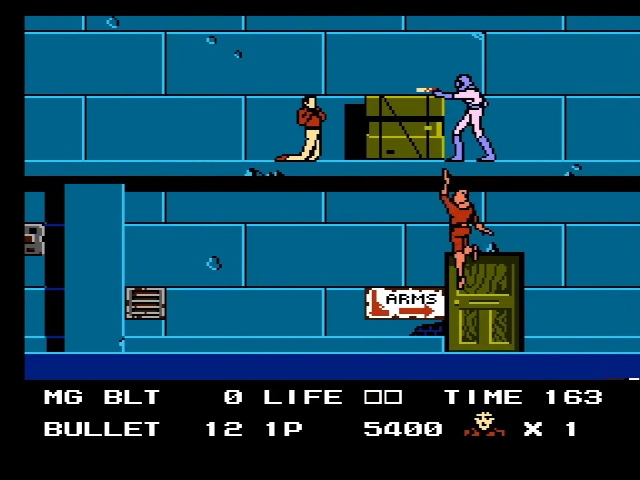

Rolling Rolling Rolling

Namco’s own successor to the Namcot 109 was the Namcot 163. This chip is often used in the chiptune scene for its advanced audio capabilities, but those aren’t accessible to a western NES, even for unlicensed games. It had a CPU cycle counter but no scanline counter. Tengen did port over one Namcot 163 title to their own RAMBO-1 chip: Rolling Thunder. This game came out in late 1989; it may be the first RAMBO-1 game.

One thing you might notice is that there’s an extra chip on the Rolling Thunder board versus the Klax. They use the same circuitboard, but there’s a chip unpopulated on Klax. As we can see, it’s a simple 74LS32 logic gate; a set of 2-input OR gates.

What is this chip doing? Notice that the CHR-ROMs are the same size; however, Rolling Thunder uses 128 kiB of CHR-ROM, while Klax uses 64 kiB. The extra chip, therefore, just adjusts for the differing pinouts of different ROM chips. I’m assuming this was a cost-saving measure to reuse the same board; given they yet again avoided using solder mask, pennies were likely being pinched.

Rolling Thunder is a pretty decent port of the arcade game. Graphics are of course massively downplayed, but I think the gameplay survives pretty well. On NES, I prefer it to the also-Tengen-published port of the similar game Shinobi, which also uses the RAMBO-1.

Currently affected by ‘Alien Syndrome’+++!

Another RAMBO-1 game, this time with a unique configuration? And a port of a Sega arcade game? Don’t mind if I do! And without solder mask? That I mind, what’s your problem Tengen?

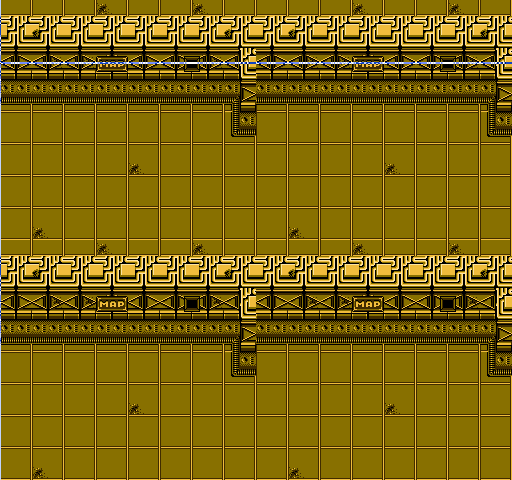

Alien Syndrome is a 1989 port of the 1987 Sega arcade title where you roam a large scrolling map, looking for your comrades and then looking for the way out. Since there’s no extra RAM on the cartridge and you scroll in two directions, you won’t be surprised to see some graphical glitches.

So, how are the nametables arranged here? Vertically? Horizontally? Neither! This has an adjustment on the PCB to use single-screen mirroring. Essentially, instead of controlling the arrangement of the two nametables in the console’s built-in CIRAM, the game cartridge controls it so you can switch between them, but they cover all four parts of the screen.

At line 0, the nametables in Alien Syndrome look like this:

But once it’s drawing the screen where your character moves, things change to look like this:

This single-screen nametable scrolling is not that different from the Sega Master System, with the added downside of attribute clash. In any case, though, it doesn’t actually require RAMBO-1 to pull off; the Japanese release of Alien Syndrome, another Sunsoft release, uses the Nintendo MMC1 for the same outcome.

It’s a bit amusing to see these Sega titles in Tengen’s challenge to the console licensing regime; the Sega Master System had a similar licensing regime, and Sega themselves would sue Accolade, who broke the Sega Genesis scheme later in 1991. (From a technical standpoint, though, the two systems had nothing in common, the NES system relying on copyright and a difficult-to-reverse engineer method, and the Sega method relying almost entirely on trademark)

Tengen Seal of Quantity

So Tengen’s plan to destroy Nintendo’s licensing regime may have failed. But they did leave behind quite a legacy; given the carts are widely available to this day, except for Tetris, they must have made some decent sales. How much of that money Nintendo’s lawyers let them keep, though, is lost to sealed settlements. Today, of course, the console licensing business is as strong as it’s ever been, and with cryptographic locks and online stores, there’s not much any enterprising Tengen of today could do.

On the other hand, Tengen not only also used a non-standard screw type on their cartridges, put one of the screws behind their sticker on the back. Even Nintendo didn’t do that!