East Meets West: The Legend of Makai

People like to say that 1980’s games are highly regionalized. You could easily recognize a European-developed game like Rare’s Wizards and Warriors, and spot a Japanese-developed game like Bashi Bazook: Morphoid Masher from a mile away. Or, at least, maybe you could have if Jaleco had actually released Bio Senshi Dan outside of Japan. But that’s not particularly important. What is that because things were much more regionalized, it’s a little more interesting when games cross those influence barriers. Take, say, Legend of Makai.

Hardware

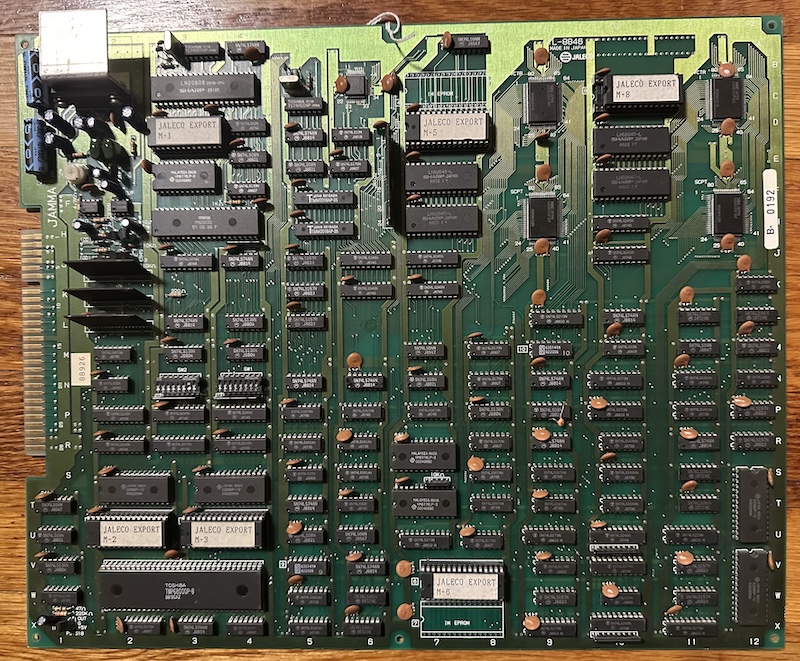

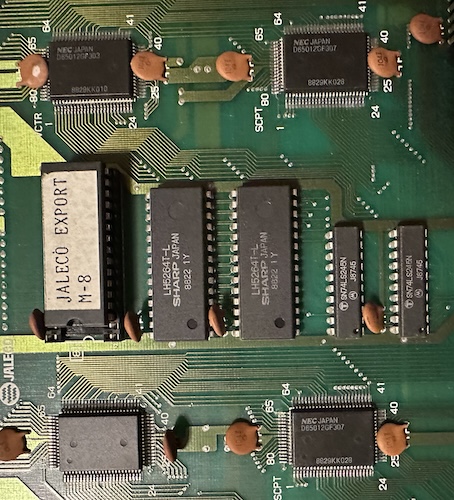

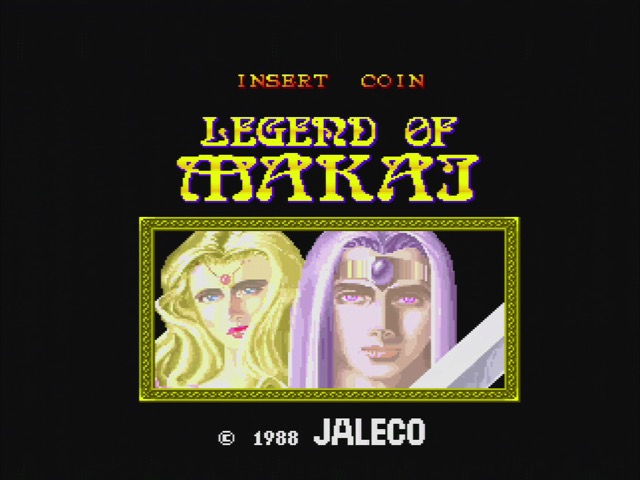

But first let’s take a look at the hardware we’ll be dealing with. Legend of Makai is a 1988 arcade game using Jaleco’s Mega System 1 chipset. Well, sort-of. This is a variant with all one board only used for this game (the “Z” variant, in enthusiast labels), while some of the later games seem to use a daughterboard for the game ROMs. So this one isn’t easily interchangeable.

This is a pretty standard late 80’s 2D arcade system. A 68000 CPU, a Z80 sound CPU, and a YM2203 (OPN) Yamaha FM chip. I swear this isn’t just Alpha68k again; it has two scrolling tilemap layers. Later non-“Z” variants had a different sound setup and another tilemap, but this blog post is about Legend of Makai.

Outside of the sound section, the board is mostly discrete logic, with a few NEC gate arrays in the corner. These gate arrays were common Jaleco parts used not only for other Mega System 1 titles, but even things like their mahjong games. It wasn’t just Konami who followed a parts-bin approach, it was everyone.

You might think that this doesn’t sound particularly impressive as an arcade board, and seems comparable to the Sega Genesis, which launched the same year as Legend of Makai. But Jaleco’s hardware had higher color depth, and being made of discrete parts, was easy for them to expand to three layers. Of course it could never be sold at retail prices, but the Sega Genesis was actually pretty impressive hardware for a home console in 1988, and Jaleco was more downmarket in the arcade industry, so it works out.

While this game was published by Jaleco on Jaleco hardware, it was developed by NMK. NMK was yet another of those development houses that thrived in Japan during this period, doing work with Jaleco for sure but not exclusively; they’re also responsible for games like Sammy-published Arkista’s Ring on the NES or the 1992 Super Dimension Fortress Macross arcade game. Oh, and the 1988 Japanese Famicom release of Wizards of Warriors (called Elrond in that region). How serendipitous.

Get to the damn legend already

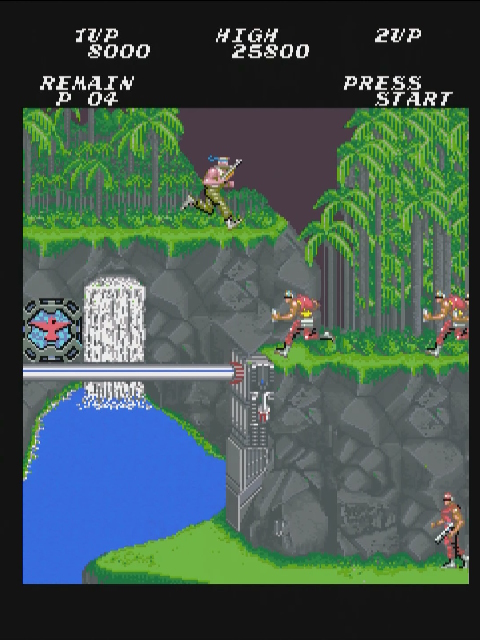

Back in 2021, I wrote up an article on Pitfall II. That console and computer game, as developed by David Crane, was then taken by Sega’s in-house development team and turned into an arcade game, with Crane’s player-friendly design balanced by the quarter-munching demands of a 1984 arcade title. Legend of Makai does not claim to be a direct port like Pitfall II; but what it is is an arcade game that’s clearly heavily inspired by Wizards and Warriors, from the company that brought Wizards and Warriors to Japan.

Wizards and Warriors was a platformer with large sprawling stages where in each stage you generally had to collect colored keys to unlock various doors and chests, with a large number of gems to collect in order to bribe a guard at the end of the stage. Legend of Makai is a platformer with large sprawling stages, where in each stage you have to collect colored keys to unlock various doors and chests.

Oddly, doors are not color-coded as they were in Wizards and Warriors. Instead, the game simply tells you the color a door requires when you go up to it. (And of course, many doors don’t require a key at all) The message is “A GREEN KEY IS ON”, which is a little odd.

Amusingly, the game actually goes out of its way to explain why the doors are so short. The game takes place in a region inhabited primarily by dwarfs.

I will say the platforming feels much more precise than Wizards and Warriors; I don’t feel like I’m going to fall off of platforms. I’m not a huge fan of how many of the jumps feel like they require the very edge of your movement to make, though– makes it hard to tell where I missed a jump and where I actually need to go get a jump enhancement item to proceed. (yep, those are back from Wizards and Warriors too) Notice that my sword is out; like Wizards and Warriors, an enemy only need to touch the sword to be damaged. And this time you can also jump on enemies, Mario-style.

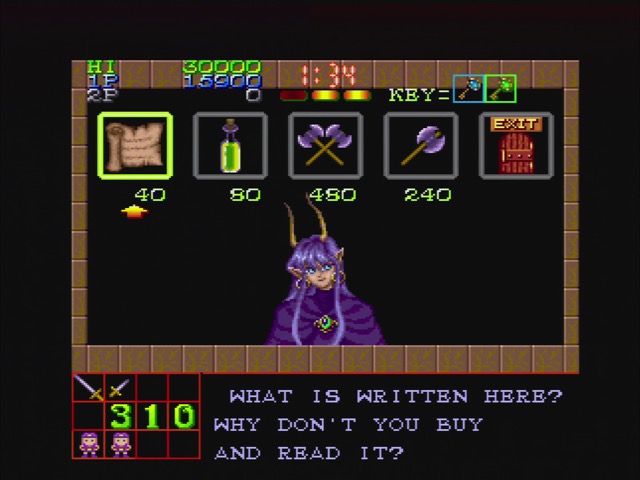

You no longer need to bribe guards, collecting gems isn’t required to progress. (Locks and keys still are) Instead, you use the gems to go to shops.

These shops sell useful items and hints to hidden secrets in the stages. We’re moving to post-Tower of Druaga design here; there are still hidden secrets with no visible indication, but now you at least can get the game itself to tell you about it.

Of course, we’re not too post-Druaga here. Items and advice cards are frequently fake, causing you to spend your hard-earned gems for nothing. And this element is actually toned down here in the “export” version; in the Japanese original, a whole host of additional shop items exist whose only purpose is to make your life worse.

Shops are a pretty natural addition from the perspective of the Japanese game industry in 1988. The post-Dragon Quest boom of adding RPG elements to games hadn’t yet fully subsided, and that included game economies.

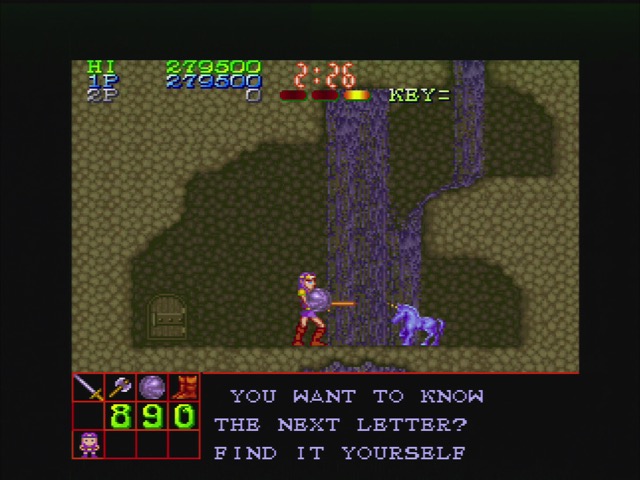

Another thing that you’ll see from other common games of the time? You have to find a specific hidden word one letter at a time, and if you don’t do that in every level, you’ll get the bad ending. This letter is given by unicorns, some of whom will argue with you, so you have to go in and out of the room– even the tropes of Japanese adventure games make their appearance here.

Oh, and one more thing– see that timer at the top of the screen? When it runs out you die. It might look like an enemy just spawned in to kill me, but my sprite is frozen– this is game over. The timer resets on every life, and on every continue, of course. Sure this is an exploration game but this is still an arcade– pay up. (The game is quite generous with continues though; you keep your items and even the damage you’ve done to a boss)

Opinion

So one thing you might notice here: the game has no parallax scrolling. Sure, lots of games don’t. But parallax scrolling was a big deal for arcade graphics in this period. And when I see arcade hardware with two tile graphics layers, I kind of assume one is going to be for the foreground and one for the background. That’s what Contra did.

Instead, Legend of Makai is using its two layers to provide UI on one layer, and gameplay on the other. A pretty straightforward thing that’s actually not that different from what Wizards and Warriors did, but instead of switching between nametables on the fly, it has two always present. Makes it clear why Jaleco would later update the Mega System 1.

So this is definitely the sort of thing that comes from playing this game in 2024 instead of 1988, but it really does have the feel of a low-end Sega Genesis game. Like something ported from the Atari ST or some other computer system where parallax was difficult, which would also explain why many of the levels are the same graphics set. Which doesn’t feel fair, but compare it to 1989’s Sega Genesis title Mystic Defender. (fun fact: actually the sequel to the Sega Master System game Spellcaster, sort-of)

And look, maybe comparing a first-party Sega game to an NMK-Jaleco joint doesn’t feel fair, but on the other hand, it’s a licensed game for a home console compared to an arcade PCB. And level 2 of Mystic Defender looks dramatically different than level 1.

And I guess that’s the thing about Legend of Makai. It’s not bad, and it takes some of the best of Wizards and Warriors and does its own thing about it. But the presentation wasn’t going to get enough quarters in 1988. But take it for what it is and there still is a pretty fun game there. But it’s not surprising NMK is better remembered for its shoot-em-ups.